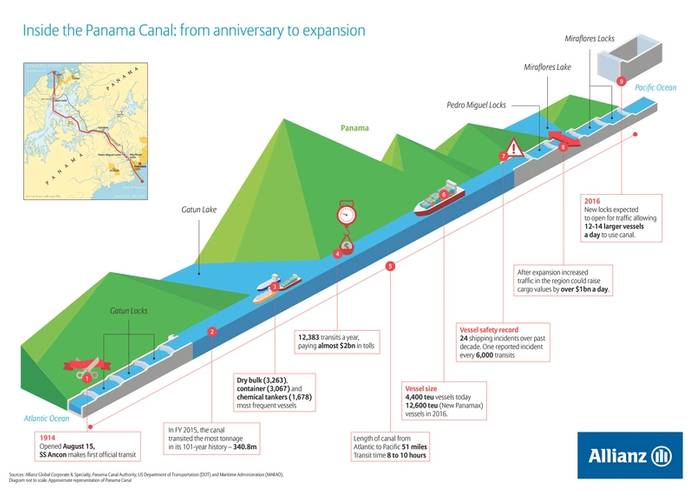

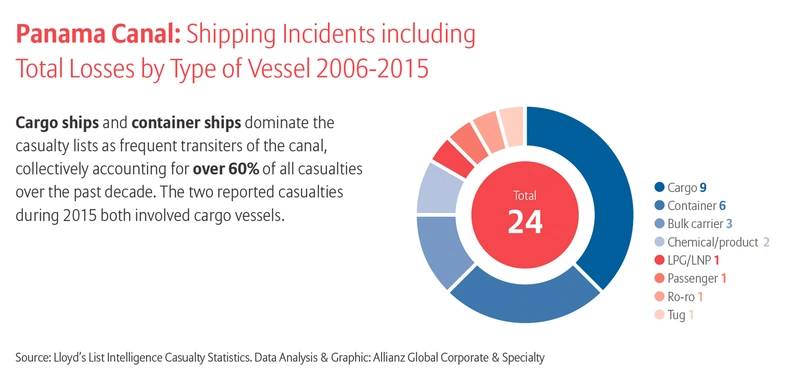

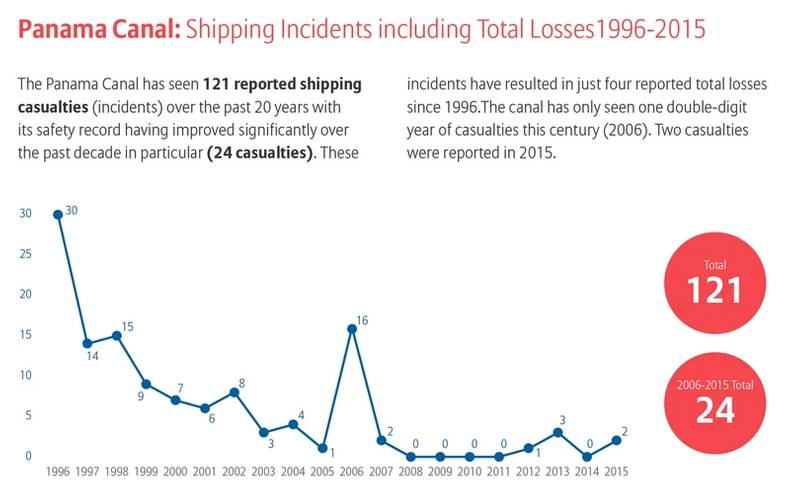

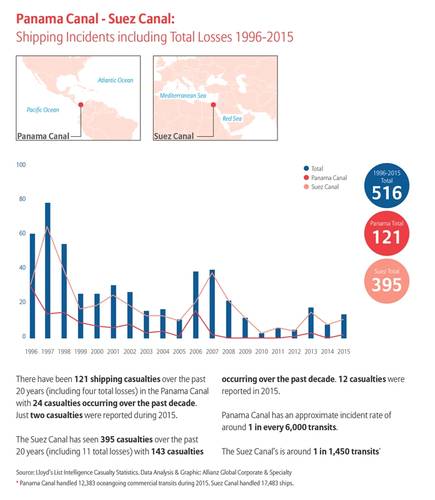

The Panama Canal’s impact on shipping routes and vessel sizes since it opened in 1914 is undisputed. This will continue with the opening of a third channel for larger vessels in 2016. This briefing examines the risk management impact of this expansion on the maritime industry.

Why is the Panama Canal Expansion Significant?

The Panama Canal’s $5.25 billion expansion increases the maximum vessel capacity and enlarges the overall volume of transported freight. Existing locks can handle ships up to 106 ft. wide, 965 ft. long, and 39.5 ft. of draft. The new locks will accommodate vessels up to 160 ft. wide, 1,200 ft. long, and 50 ft. deep. Container ship capacities will increase from 4,400 to about 13,000 teus. The new locks create a third lane of traffic for larger “New Panamax” vessels. The expansion is significant because it impacts the size and frequency of vessels that call on the U.S. East and Gulf Coast ports, which presently have to use the Suez Canal coming to the U.S. from Asia.

The Impact

The Panama Canal Authority (ACP) estimates that the combined effect of 12 to 14 larger Panamax vessels per day (an average of approximately 4,750 ships a year) combined with continued smaller vessel transits will double capacity, increasing Canal throughput from 300m tons to 600m tons PCUMS (Panama Canal Universal Measuring System). PCUMS is the basis upon which vessels are charged for use of the Canal: one PCUMS ton is approximately 100 cubic feet of cargo space. A twenty foot long container (teu) is equivalent to approximately 13 PCUMS tons.

Insured Goods

The value of insured goods transported will increase with the expanded Canal, as will the risk accumulation. This is the reason why proactive loss controls will continue to be needed; including tracking of the risk accumulation. This is one of the biggest lessons learned from the Tianjin explosion in China last year. In particular, the New Panamax ships will be impacted. For example, a fully-loaded 12,600 teu container ship could have an average insured cargo value of $250 million, based on an average value of $20,000 per teu. With the cargo-carrying capacity of ships transiting the Canal having the potential to double following expansion, we can approximately assume this could result in an additional $1.25 billion in insured goods passing through the Canal in just one given day. According to Captain Rahul Khanna, Global Head of Marine Risk Consulting, AGCS, the Canal’s expansion may also lead to an increase in the number of vessels waiting to undertake the transit on both the Atlantic and Pacific sides. “This means that with the values concentrated in the surrounding area, from an accumulation point of view, this figure could be even higher,” he said.

Another potential risk is that higher concentrations of insured goods will be transported on bigger ships, which will call in at U.S. ports and terminals, many of which are exposed to hurricanes. For example, a large portion of Superstorm Sandy losses in 2012 were due to storm surge that flooded ports in the Northeast region. According to AGCS’ Safety and Shipping Review 2016, meteorological predictions anticipate more extreme weather conditions, bringing additional safety risks for shipping and potential disruption to supply chains. Hurricanes and bad weather were contributing factors to at least three of the five largest vessels lost during 2015.

How will Risk Management be Impacted?

With the increase in size of vessels transiting the Canal, you have a corresponding increase in operational, environmental and commercial risks.Bigger ships automatically pose greater risks in that the sheer amount of cargo carried dictates that a serious casualty has the potential to lead to a sizable loss and greater disruption. Increasing traffic of bigger ships means the amount of diesel and petroleum being transported could also pose a heightened pollution risk in the event of a casualty.

Conversely, the prospect of an expanded all-water route from Asia to the U.S. East/Gulf coasts could actually lead to a risk reduction in another area because containers will no longer need to be moved/reloaded onto trains. The fewer times you have to handle a container the lower the risk of damage.

According to ACP, the Panama Canal has invested heavily in training resources, prevention programs and contingency plans in order to maintain its excellent safety record . Hands-on education, preparation, and training programs will help ensure that both the existing and new locks will run seamlessly. Some of the programs are related to the training of the Canal’s pilots and tugboat captains, consisting of simulation and hands-on experience with transit training on a chartered New Panamax vessel. Kinsey describes training as “key to mitigating the risks involved with larger vessels”. With such an important emphasis on training, human error is unlikely to be the main cause of shipping incidents in the Canal.

But the risk of grounding remains, either as a result of equipment failure or a casualty on the ship. Insurance companies will need to consider re-evaluating the routine risk to securing and monitoring containers under the new scenario, says Captain William Hansen, Senior Marine Risk Engineer, AGCS. A grounding of one of the larger ships in the Canal will cause severe disruption. Given the fact that the new locks will not be using the traditional “mules” but rather tugs which will be in the lock chamber with the vessel that is locking through there is the potential for increased contact with the lock walls, Kinsey believes. “It is believed that the use of tugs rather than mules provides sufficient control over ships in the lock chamber, but it is a situation that will be monitored closely,” he adds.

Khanna agrees that the level of training provided to pilots ahead of opening will be “extremely important” as the expansion of the Canal represents a “new shipping environment for many mariners”. However, he also notes it cannot prepare mariners 100 percent for the live environment. “Although much training will be given it can only be done on a few vessels. But when the Canal is opened for real, a whole host of different vessels with different characteristics will be passing through. That will be a challenge.”

Then there is particular concern surrounding the salvage limitations for the latest generation of container ships. In the event of an accident in the surrounding region there may be an insufficient number of qualified, experienced salvage experts available to handle the New Panamax ships due to merger and acquisition activity and economic pressures.

Risk Challenges?

Most U.S. East and Gulf coast ports are being dredged in preparation for the New Panamax ships and are upgrading equipment, although each is at varying degrees of readiness. Larger and more ship-to-shore cranes are required to handle increased container volumes. While Panamax-sized ships can be worked by four or five cranes, larger ships will need to be worked with at least six cranes.

Ports are attempting to get into the game and stay in the game. There is substantial commercial risk on the East Coast with ports expanding their container capacity in the hope of gaining market share.

Ports in the U.S. West Coast have also spent millions to expand their capacity in order to protect a market share that they already have. “Additional infrastructure upgrades will be needed to handle the increase in volume/throughput. Another major challenge is the actual handling of larger vessels. Port operating procedures will have to be reviewed with regard to wind and weather constraints given the tight operating margins that these ships will be facing.” This means port and shipping workers must undergo training in order to mitigate any operational risks.

And of course the potential impact of any shipping incident is much wider than just impeding progress through the Panama Canal. With more larger ships on the move in the surrounding region any incident could also impede traffic at major ports in the U.S. and elsewhere, resulting in a potential increase in business interruption losses.

Panama Canal Fast Facts

This risk briefing updates, and adds to, information in the AGCS report Panama Canal 100: Shipping Safety and Future Risks, originally published August 2014. The report can be

viewed here.

- All gates at the new locks are the same length, 57.6m, but they are of varying heights, depending on their placement along the Canal, with the tallest 33.04m high (the equivalent of an 11 story building)

- March, August and December were the busiest transit months through the Canal in 2015; slowest months were February, September and June.

- To date, the expansion project has generated more than 31,000 direct jobs.

- Toll revenues through the Canal were $1.994 billion in FY2015, a 4.4 percent increase from FY2014.

- Revenues from full container vessels (fully loaded ships) represented 47.4 percent of all tolls collected in FY2015

- Since the Canal first opened in 1914, it has provided transit service to more than 815,000 vessels.

Source: Panama Canal Authority

The Author

Captain Andrew Kinsey spent 23 years in the U.S. Merchant Marine and U.S. Naval Reserve, sailing in all licensed ranks, including Master. His sailing experience was primarily with Maersk Lines, sailing as Master of three different Container ships. He also served as Master aboard two Military Sealift Command (MSC), Large Medium Speed RORO (LMSR) ships, the USNS “Sisler” and USNS “Red Cloud.” He served in Operations Desert Shield & Desert Storm, Restore Hope, Enduring Freedom and Iraqi Freedom, and received numerous decorations and awards. After coming ashore in 2006, Andrew worked as an independent Marine Surveyor in the Tri-state area and joined the ACE/US Commercial Marine - Marine Advisory Service, in 2009. At ACE he was responsible for providing a wide range of Risk Control services to support its commercial book of marine business, including Cargo, Project Cargo, Hull & Machinery, Terminal Operators, and related Inland Marine LOB’s.

Andrew is a graduate of the United States Merchant Marine Academy at Kings Point, NY (1984) and holds a Bachelor’s degree in Marine Transportation/ Nautical Science. He also holds an Unlimited U.S. Coast Guard Masters License, for vessels of any gross tonnage upon oceans. He is based in New York.