We are in the midst of a revolution over port infrastructure. This revolution is not about the role of ports as silent engines for our economy and the need for better intermodal infrastructure. Rather, it is about why governments – local, state and federal – believe ports exist, and whether or not public and private entities, other than those directly responsible for ports, should help build or improve port infrastructure and their intermodal connectors.

Ports are rightfully linked to a maritime industry that is steeped in tradition. Their definition, which predates the age of pirates by over 450 years, reflects this fact. Per Merriam Webster’s Dictionary, ports have had the same two definitions since before the 12th Century: ‘a place where ships may ride secure from storms’; and ‘a harbor town or city where ships may take on or discharge cargo’. The next logical question to ask is: should the 21st Century definition of a port remain the same as it has been since Latin was a common language? Are maritime ports primarily a safe haven for ships? Or are they the ultimate intermodal hub, where trucks and trains come alongside ships and barges to exchange freight. And why does this matter?

Traditionally, ports were built by the people and communities who lived near waterfronts. They owned ships or worked in or near a port, basing their local economy on cargoes transported through their region. Today’s ports serve larger, more heavily populated, regional economies, and some serve national needs. Yesterday’s ports were made from timber and were designed for yesterday’s ships. Docks built as recent as 1985 have been built from stronger materials, and have a life expectancy of 40 to 50 years, but were not designed to accommodate ships that began sailing only 15 years later, in 2000. Today’s intermodal logistics operations – from ships to trucks and trains – are evolving rapidly, outgrowing infrastructure built less than 20 years ago. Who should ensure that the regional or national ports and multimodal connectors being built today are capable of transporting people and freight 20 to 40 years from now?

There has been a flurry recently of government interest in ports. This is also true within the U.S. Department of Transportation, which is responsible for the many facets of our national transportation system. With a strong heritage of safety, and a mission that strives to ensure a fast, safe, efficient, accessible and convenient transportation system, the Department views ports as a part of the overall system. When the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act was launched in 2009, it established the first national multimodal infrastructure discretionary grant program that included ports as eligible applicants.

Beginning in 2010, the TIGER discretionary grant program also offered funding to infrastructure projects for all modes of transportation including ports, and it has been oversubscribed in every one of its eight Rounds. The FAST Act of December 2015 established the freight infrastructure grants under the FASTLANE program – and ports are once again invited to compete with the other modes. A pattern is emerging where ports are eligible to compete for freight infrastructure funds because they are a part of our nation’s transportation system … and not because they are ports.

In 2010, the National Defense Authorization Act authorized the Maritime Administration (MARAD) to establish the Port Infrastructure Development Program to promote, encourage, and develop ports and transportation facilities in connection with water commerce. MARAD works hard to assist ports and communities meet future regional and national freight needs. We do this by administering programs such as TIGER and FASTLANE, as well as exploring what other federal programs may be available to help ports. But sometimes ports – the ultimate intermodal hubs of the U.S. – have difficulty competing for funds under other programs. And why does this matter?

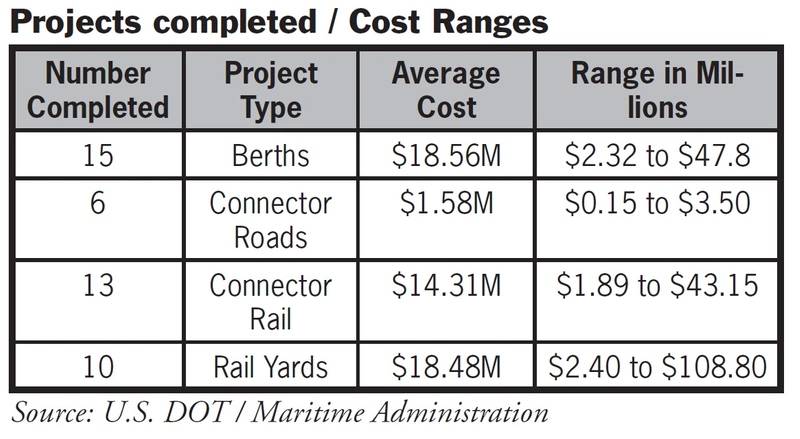

An analysis of TIGER funded projects tells the story. MARAD has helped complete 44 intermodal projects at ports that were funded through the Department’s TIGER discretionary grant program. Analysis of data collected from these projects reveals a wide range in costs for four main project types. (This is understandable as some projects are more complex than others.) If we just look at the average cost, it does not seem daunting for regions to get port and intermodal infrastructure ready for the next 40 to 50 years.

But we need to realize that these grant awards cover only a portion of the industries’ infrastructure needs. In 2015, the American Association of Port Authorities identified 125 additional projects at its member ports that are estimated to cost $28.9 billion, and we can wonder how those improvements will be made. If ports cannot afford to improve facilities through traditional means, what options are available to them? Will investors – public or private – see a good investment in a safe harbor?

I argue that the definition of ports, our perception of them and how we talk about them will determine the future ability of communities and our nation to attract partners who will care enough to ensure that ports – as part of our national system of transportation systems – will be able to meet our future freight needs. Who will rise to champion a revolution in our public perception of ports – and who will champion a better definition for the 21st Century?

The Author

Lauren K. Brand, a member of the Senior Executive Service, became the Associate Administrator responsible for Ports and Waterways programs within the Maritime Administration in January 2015. In this capacity, Mrs. Brand directs StrongPorts, a national port infrastructure modernization program in excess of $1.7 billion – that includes TIGER and FASTLANE discretionary funds as well as other federal assistance. She is responsible for the continued development of America’s Marine Highway initiative and manages the Agency’s offshore energy licensing projects (the Deepwater Port Program).

(As published in the December 2016 edition of

Marine News)