Beirut Port Explosion Echoes the 1917 Halifax Harbor Blast

As the scope of the August 4 explosion at the port of Beirut becomes clear, the tolls of the loss of life, injuries, homelessness and property damage are staggering. In the immediate chaos of large explosions, it can be difficult to make sense of what has happened.

There are numerous similarities between the 2020 Beirut port explosion and the 1917 Halifax Harbor Explosion that can help us make sense of what has happened in Beirut.

In 2017, I was part of a group of hazards researchers who met in Halifax to reflect on aspects of the Halifax Explosion for its 100th anniversary. Such historical disaster case study information is especially relevant now.

The big picture story unfortunately repeats itself: a precarious situation of hazardous materials at an industrial port, circumstances of a fire leading to a massive explosion and a disaster of historical proportions.

Explosive collision

On the morning of December 6, 1917, a navigation accident occurred where two vessels collided in the narrows of the Halifax Harbor.

One of the ships in the collision, the Mont-Blanc, was dangerously overladen with hazardous cargo, including explosives in its bulk cargo hold and barrels of petrochemicals on the deck. When another ship, the Imo, accidentally struck the Mont-Blanc’s bow, sparks from the grinding metal ignited a fire on the deck. The fire burned for about 20 minutes until a violent chemical chain reaction ignited. At 9:04 am local time, the Mont-Blanc’s 2,925 tonnes of explosives on board detonated violently.

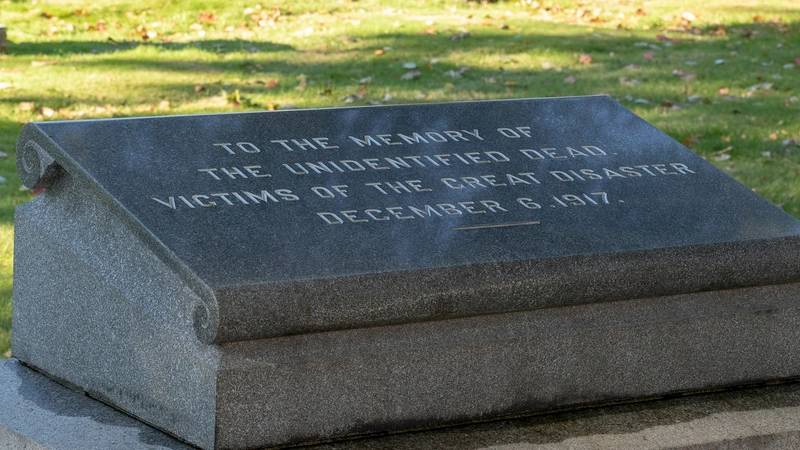

A segment of an anchor on a cement block.

While most of the Mont Blanc was vaporized in the blast, the ship’s 517-kilogram anchor shaft was propelled approximately four kilometers from the point of the explosion. It is now part of a historical monument which attests to the power of the blast.

In the explosion’s aftermath, an enormous cloud of smoke and debris rose, and the bustling port district on Halifax’s north end was reduced to ruins. In the end, the casualty toll stood at 1,963 dead with another 9,000 injured.

Similar injuries

One immediate point of similarity between the Halifax and Beirut explosions is the type of injuries observed. Blast waves interact with people directly and indirectly, potentially affecting multiple systems in the body.

The physics of blast phenomena help us to understand the dangers. Large explosions are accompanied by a shock wave, an invisible phenomenon that can travel at several times the speed of sound and reach pressures of 10 or more atmospheres.

The wind that immediately follows the shock wave is brief but very intense and carries fragments of debris. The sound waves, or the loud boom, travel slower and arrive at the observer last. This sequence of events occurs faster than one can react. Depending on how close one is to the explosion, there may not even be time to duck.

In Halifax, many people were killed or injured from flying debris and glass. An inordinate number of penetrating eye injuries occurred.

The Mont-Blanc burned for 20 minutes prior to its explosion, and many people watched the spectacle of the burning ship. As this disaster happened in December, bystanders watched from indoors, through glass windows. When the massive blast occurred, many were injured by flying glass; the Halifax Explosion is sometimes referred to as the “blizzard of glass.”

From images we have seen coming out of Beirut, the characteristics are consistent with a massive conventional explosion. Video taken by bystanders has shown multiple smaller explosions with a growing colorful smoke cloud, followed by a very quick appearance and disappearance of a white spherical blast shock wave, made visible by the condensation of water vapor in the air. From some angles, it appears as a mushroom cloud. Then the cameras get shaky and lose focus as debris, driven by hurricane-force winds, hits the observers head-on.

Media images of bloody survivors and the walking wounded from Beirut are similar to witness accounts from survivors of the Halifax Explosion. In 1917, explosion witnesses did not have cell phone cameras, but if they did the images would be similar to what we are seeing from Beirut.

Port fires

Whether in 1917 or 2020, bystanders will be drawn to watch fires at industrial ports. If, by chance, you are watching an industrial fire and have any reason to suspect a large explosion may be possible, blast safety instructions suggest putting distance between yourself and the fire, seeking cover behind something, getting under a sturdy table, moving to an interior room and avoiding watching from windows.

If one happens upon a large blaze at a port, rail yard or industrial facility that appears like a holiday firework show, it is difficult to guess exactly what is happening at the heart of the fire. For Beirut, we now know that 2,750 tonnes of ammonium nitrate, sitting in a warehouse unattended for more than six years, was in the middle of the fire.

A 103-year-old lesson from the Halifax Harbor Explosion is the same as a recent lesson from the Beirut port explosion: the risks are high when watching industrial fires at ports, even from what may seem to be a safe distance.

© Kelly Mercer / Adobe Stock

© Kelly Mercer / Adobe Stock

The Author

Jack L. Rozdilsky is Associate Professor of Disaster and Emergency Management at York University, Canada.

(Source: The Conversation)