MMA's Brad Lima Talks Maritime Education and Beyond

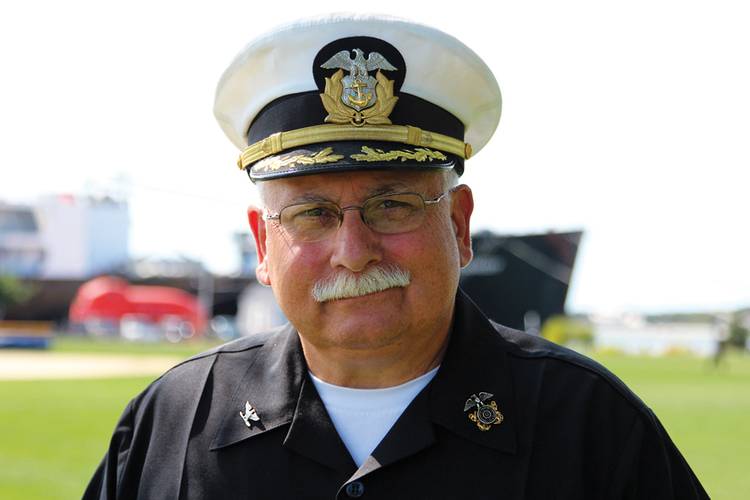

Maritime employers, thirsting for quality employees in numbers sufficient to run their far flung businesses, continue to struggle to recruit and retain talent despite lingering high unemployment across the other sectors of the economy. On the waterfront, there are many models for producing marine professionals; some quite new and others, time tested. Brad Lima is the Dean and Vice President for Academic Affairs at the Massachusetts Maritime Academy. As a 1974 graduate (BS; marine engineering) of the nation’s oldest continuously operating academy, he also boasts experience as a licensed seagoing engineer with an oil major, as a reserve officer in the United States Naval Reserve and additionally has earned a master’s degree in Management along the way. Lima has served as U.S. Delegate to the International Maritime Organization Council. Through the years, Lima has seen all of the changes – from outside and looking into the current maritime educational system in this country. As uniquely qualified to comment on this subject as anyone else, he is additionally responsible for a $9,000,000 operating budget with 75 full-time faculty, 75 part-time faculty and an administrative staff of ten. In addition to his Unlimited horsepower Chief Engineer’s license, Lima also possesses a Chief Engineer Stationary Engineering License and is a Certified Plant Engineer (CPE), along with myriad other technical qualifications too numerous to mention here. Listen in as he shares the formula for producing the next generation of marine professionals.

The methods used by maritime educators have changed radically over the past 25 years. What’s the biggest of those changes?

The biggest change, of course, is the addition of the international STCW standards to the curriculum. U.S. maritime academies satisfy regional and specialized accreditation standards, STCW standards, and national standards while also attempting to provide the industry specialized certifications such as VSO, PIC, DP, Fast Rescue Boat, and for engineers, Refrigerant Recovery certification. The real challenge is to accomplish all of the requirements of STCW and all of the requirements of national regulation while maintaining academic accreditation and maintaining a four-year graduation time frame. “Seasoning” comes after graduation: only after a student has received the educational foundation to be a good mate or engineer do they leave the academies and learn from the school of hard knocks. The U.S. maritime academies’ philosophy of producing a well-educated and properly trained mate or engineer has never wavered, but is fundamentally different from the international model of STCW, which is based on the apprenticeship concept; front loading experience at the expense of education. Although the American educational challenges have been brought forward at IMO in London, the international maritime community has little sympathy for the U.S. academies. In addition to the rapidly changing regulatory environment, technology is changing and the range of topics that students must learn and prepare for the USCG licensing exams is staggering. We live in the real world in which ECDIS has replaced paper charts and dynamic positioning is the hot new trend. Yet, domestic requirements still have an entire module of the USCG exam that tests on Celestial Navigation. It is hard to grasp in this day of technology the number of hours of practice that a cadet must apply to be able to perform a three star fix within one-half mile of accuracy when the reality of needing this skill is as remote as using a slide rule.

Can maritime academies absorb the additional burden of STCW and maintain a four year university-style experience?

Prior to STCW, the maritime academies needed to satisfy accreditation standards, while cadets obtained the necessary sea service and they passed the USCG exam. When STCW came into effect, the academies were told that they would not feel the impact of STCW. STCW compliance today has a hefty price tag of approximately $5,000,000 annually for all the state maritime academies. The additional STCW load results in “Ghost Credits” – time which is required of a cadet to satisfy STCW but has no academic credit) – which can easily be equated to an additional semester of academic load. Can the academies continue to graduate a cadet in four years? Yes, especially when you realize that a calendar year has 12 months and that all the months are used to satisfy regulatory requirements. It is not uncommon for a cadet to carry 17 to 19 credits in a single semester. The academic credit load for any of the maritime academies license programs is comparable to five years worth of study and that does not include the semester worth of Ghost Credits. Success at any of the maritime academies, therefore, can be attributed in part to exceptional time management skills. STCW has become an additional layer of requirements on top of all necessary training to prepare a cadet for the USCG exam. The hardest point to grasp is that the competency measures for U.S. seafarers, prior to STCW implementation, do not satisfy a single element of STCW. Domestic regulations and international standards have become polarized when harmonization of the two should be the course chosen. We maritime academies have been told that things will get better and we will be able to ascertain this once the proposed rule making becomes final.

So-called brown water vessels comprise all but 500 hulls in the U.S. Merchant Marine. Give us a few examples of how you are altering curriculum to reflect this fact.

To meet the needs of the incredible opportunities that the inland and offshore towing industry provides, the Academy created the MMA Mate of Towing Vessels Program. This program provides theoretical knowledge and practical hands on training required for our cadets to obtain the “Mate (Pilot) of Towing Vessels” endorsement to their Third Mate license. To support the practical training, the Academy invested heavily by acquired two training tugs, and a barge. Cadets get underway under the supervision of designated examiners to practice maneuvering tasks required in the Towing Officer Assessment Record. Additionally, the Academy installed a state of the art towing simulator. Here, cadets are trained in all aspects of towing including inland towboats, coastal towing, articulated tug and barge, ship assist, and azimuthing drive operations.

Mass. Maritime for many years had just two majors – deck and engine. Graduates, for the most part, who went to sea for a living on deep draft bluewater tonnage. Which sector of the maritime industry now receives a simple majority of your product?

Actually, the Military Sealift Command continues to hire more Mass Maritime graduates than any other single employer. A total of 25 graduates from the class of 2013 made their decision to hire on with MSC this year. Interestingly though, a total of 29 new graduates were hired by companies in the oil and energy fields, especially those based out of the Gulf of Mexico. Some of these companies included Otto Candies, Kirby, Noble, and Sea Drill and offered jobs afloat to Marine Engineering and Marine Transportation graduates. The next largest sector of industry that our cadets go to is shore-based engineering firms, such as Entergy, Ensco, Siemens, Able Engineering and Veolia Engineering.

What percentage of graduates go to sea versus immediately working office and/or land-based positions?

Licensed graduates comprise about 45 percent of the graduating seniors and the vast majority of these students work afloat after graduation. Less than 5 percent of these students report taking jobs ashore. Graduates from our other majors, Marine Safety and Environmental Protection, International Maritime Business, Facilities Engineering and Emergency Management typically seek shoreside positions. As many as 15 percent of those graduates, however, will seek employment at sea – for example, as Environmental Officers on cruise ships. What our statistics tell us is that our graduates seek and are offered employment in the fields that they study for, which indicates to us that we are remaining current and are able to prepare our students for the real world.

What is the long term trend for cadets in terms of their focus for chosen careers, post-graduation?

The present freshman and sophomore classes show a significant increase in selecting the USCG license programs. This is in part due to increased opportunities in brown water and off shore exploration. The numbers of senior mate candidates stands at 65 while the freshman class has 94. A total of 78 marine engineer candidates in our senior class contrast sharply to the freshman class total of 161. For some cadets, the challenge is the license exam at the end of four years of arduous study which sends a signal to employers that they have met a challenge that others may never achieve in their working career. We know that engineers are more likely to come ashore earlier in their career due to highly transferable skills, but employers want those who know how to be part of a team and play by a prescribed set of rules. We are finding graduates after shipping being employed by municipal, state and federal agencies because of their work ethic. National Defense contractors find our graduates employable due to the ability to be decisive and resourceful while spending long periods of time away from home. We are initiating a study to measure to see where graduates are; two and five years out and see what path they opted to get there.

Inland companies long complained that maritime academy graduates are poorly prepared for inland/towing careers. What are you doing to improve the performance of these graduates when they first enter the workforce?

By interacting with the inland industry, the academy has gotten a much better understanding of the employer’s needs and the knowledge required of our graduates. At the same time, employers have gotten a much better understanding of the mission of Massachusetts Maritime Academy and the type of graduates that we produce. We focused our energies on meeting the employer’s needs and educating our cadets not just on the professional requirements of the job, but the career opportunities available in the inland towing industry. Our graduates understand that while they are highly trained, they are not going to walk directly into the wheelhouse of a towing vessel. The towing industry requires a level of knowledge of the particulars of the vessels involved and the inland/western river waters only learned by hands on experience. Our graduates actually welcome six months to a year of training before being cut loose as a Mate or Pilot of a towing vessel and the towing companies understand they are getting highly trained mariners that need to be “seasoned” in the particulars of their trade. Each summer, MMA sends cadets to our partner companies such as Kirby Inland Marine for six to eight weeks. During the internships, cadets work aboard tugs and barges gaining great experience and insight into the inland towing industry.

The practice of “performance based assessments” is a growing trend in industry. These assessments typically go far beyond mere STCW compliance. Although so far primarily a blue water practice, it is occurring in brown water, too. Are cadets getting enough simulator time at present to prepare them for the real world?

Performance-based assessments are a method of determining if a student can perform a task or ability at a pre-determined level of competency. Sometimes the assessments are performed on board vessels, such as the T/S Kennedy, and sometimes these assessments are completed in the simulator. While both teaching platforms have their strengths, simulators are wonderful teaching and learning tools because of the endless array of situations that a student can be taught or tested in without risk. Simulation is such an important part of the curriculum that the average Marine Transportation cadet takes about 20 percent of their credit load in simulation-based courses. Simulators, however, are a costly investment. A maritime academy preparing new third mates must acquire simulation for Radar/ARPA, ECDIS, Full Mission Bridge and GMDSS in order to ensure that STCW standards are being met. Expenditures in simulation at the Massachusetts Maritime Academy total about $3.5 million in the past three years alone. These expenditures include a new 360°-full mission bridge simulator and necessary updates to our Radar/ARPA simulators. Massachusetts Maritime Academy now also has a full time staff of four Information Technology employees that directly support the simulation program.

Engineroom simulation is also becoming more prevalent. Tell us about the capabilities of your engineering department in this way – especially since you still produce about twice as many engineers as licensed deck officers.

We presently are using pc-based engineering software instead of full mission simulation for engineers. Dialogue recently occurred with this academy asking the National Maritime Center (NMC) if PC-based software would satisfy assessment standards. NMC has said that they will review the submission, but in general, the U.S. academies have discussed this topic and see very cost effective value in PC-based simulation which can include faults while providing authentic system interface. The maritime academies are fully support of PC-based desk top simulation for the engineers, especially knowing that entire propulsion plants can today be operated from a computer monitor.

Finally, attending a quasi-military academy probably isn’t for everyone. With so much competition from the so-called “apprentice” programs in the coastal and inland workboat trades, what can you offer as the primary benefit to hiring one of yours, as oppose to somebody else?

The 46 CFR Part 310 requires the U.S. maritime academy cadets to participate in a minimum of three years of regimental structure. A regimental program first instills how to be a good follower, where one learn how to takes orders, followed by a prescribed set of rules and become part of a team while being responsible for themselves and their shipmates. Followship then converts to leadership as an upperclassman, where now management and leadership blend to test varying degree of responsibility while honing critical think skills. A seafarer must be able to make good decisions based on variables provided at any moment in time. A common thread woven among all the skills required of seafarers is critical thinking. The educational process which occurs both in and out of the classroom at a maritime academy emphasizes the importance and honing of critical thinking skills. Good critical thinking skills results in a decisive person making the right decisions which results in strengthening one’s confidence to lead and manage others. That’s the real value in the maritime Academy style of education.

(As published in the October 2013 edition of Marine News - www.marinelink.com)