Eye on Design: A Titanium USS Enterprise (NCC-1701 that is)

Dennis Bryant provided a link to a story about the USCG Cutter Bear in his March 18, 2020 newsletter. It is a great story about a great ship with a great Captain (Michael Healy) and a great crew. It shows that the right combination of ship and crew can perform miracles.

This one ship, its Captain (and his wife who often shipped with him), and its crew did so many things so well that it has become the stuff of legends. I will not further discuss these adventures; some can be found in the article and the rest can be easily Googled. Instead I want to draw attention to the lovely photo of the vessel in the article. I was awestruck by her beauty. Not the come hither style of beauty (even though in that category she is well endowed too). Rather I was struck by her functional beauty. This ship is the best looking Swiss army knife I have ever seen.

If somebody were to tell me that I would be sent “on a five-year mission: to explore strange new worlds. To seek out new life and new civilizations. To boldly go where no man has gone before!” this would be the vessel I would pick, even today.

OK, I may do a little technological upgrade, after all I am an engineer, but this would be the starting point and I would be loath to deviate too much.

Instead of steam, I would fit internal combustion engines, but probably work out a more complex hybrid diesel electric arrangement. I would not install a huge amount of power. (Her original propulsion power was only 300 IHP.) I would fit her with a sturdy CPP. With her electric drive she could be rigged for free running, sail charging or even some boost power to drive through ice. And she would be air-conditioned.

I would keep her brigantine rig, but rigged with more modern sails and maybe a Dynarig (Maltese Falcon) style square rigged foremast.

My biggest dilemma would be to decide whether to keep her stack. There would be no need for that tall stack and I could rig more sail, but, my God, what a gorgeous stack!

Then come the boats. I’d have a few RIBs (electric outboard powered), but undoubtedly also two much lower speed electric launches with simple galley and bunks and auxiliary sail on freestanding masts that can function as independent exploration/research vessels.

At one stage the Bear was fitted with a seaplane, but drones will perform that work today. A manned submarine would be sexy, but I think it would make more sense to use ROV’s.

She would be fitted with excellent awnings, there is nothing better than shade when working on deck. Altogether it would be the boat of Jacques Cousteau’s (and my) dreams.

There is actually only one big change that I would make and that relates to the history of the Bear herself and too many other great ships and boats.

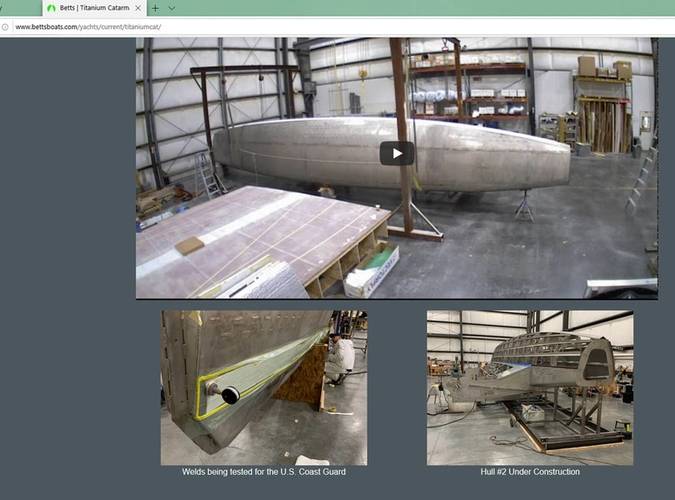

50 ft Titanium Sailing Catamarn Demihull Mock up Note Trapezoidal shaped stringers at Bettsboats Anacortes WA

50 ft Titanium Sailing Catamarn Demihull Mock up Note Trapezoidal shaped stringers at Bettsboats Anacortes WA

Photo courtesy Jim Betts www.bettsboats.com

Depending on how you count, the Bear had an active career that exceeded 70 years. She then saw reduced service and sank at nearly 90 years of age, while she was under tow to become a static exhibit vessel. Apparently she lost a mast when the tow line broke, and sank when her hull was punctured by the mast.

I am sure her 70-year life was the result of both her Swiss army knife capabilities and her extremely heavy wooden construction to allow ice service. Nevertheless, almost certainly, she was removed from active service when her hull maintenance became too much of a burden. Many ships like this are then regarded as potential museum vessels, but museum vessel economics are extremely problematic and museum status is really only a sad testament to a vessel’s loss of vitality.

Let’s face it, the Bear did not die because she was obsolete, but rather because her hull structure was worn out. Remarkably, based on my wish list for a Bear replica outlined above, I could have modernized the original Bear for my mission if her hull had not worn out.

That indicates that if I were to build my Bear replica today, I should build her with an unlimited hull life. That would mean I would build her out of stainless steel, or even better; titanium.

Nobody uses those material for large vessel construction. So am I crazy? Or is the whole world wrong and am I right? I think I am right in this case and there may be other cases too.

I was first confronted with titanium as a hull material about 20 years ago. A friend of mine, Capt. Craig Tafoya, told me he had good connections with Russian titanium suppliers and wondered if it may be cost effective to build floating drydocks out of titanium. His idea was very interesting and in some ways conforms to what I described above. Nobody throws drydocks away until they are rotten to the core, but the economics for drydocks are dicey, because drydocks are an upfront investment to make money over time. The less you spend at start up, the better your chance at cost recovery. Another friend of mine, the yacht designer Bruce Marek, with his partner Bruce Nelson, designed a titanium sailboat for a Japanese customer decades ago. This customer owned a titanium manufacturing business and built the boat himself. The boat was, and is, great, but since sailing yacht hull shape fashions still change so much over time, an old titanium sailing yacht hull does not compete against a new composite hull.

But here Bear comes back into the picture. Bear’s hull was perfectly adequate for over 70 years and even almost 150 years later is perfectly adequate for her envisioned use (a research/long range patrol/training/discovery/remote community support vessel). Moreover, it is highly unlikely that 100 years into the future she cannot do what she did 150 years ago. And here the economics become interesting.

Suppose the hull costs three times the cost of a steel hull (a not crazy assumption), that will still only increase her overall cost by, say 25%. That will be counterbalanced by massively reduced maintenance costs, and she will always be a very attractive candidate for continuous upgrade, ensuring her continued existence. In other words, build the Bear out of titanium, and we will never have to think about building a replica and never see a noble vessel like this die an ignominious death.

So for what other vessels should we think in terms of eternal hulls? Sail training vessels (like the USCG Eagle)? Aircraft carriers? Research vessels? Cruise vessels? Tugs? Staten Island ferries? The hull design (shape) would have to be mature, and its technology upgrade expected.

Those hulls are out there. The Navy has looked at titanium construction for years, but are constrained in starting titanium construction due to an aversion by congress on infrastructure spending. Still, a few years ago, I heard a US Navy admiral say that the US Navy spends 20% of its maintenance budget on corrosion prevention. Let’s run those numbers against the cost of titanium.

For each column I write, MREN has agreed to make a small donation to an organization of my choice. For this column I nominate the Cousteau Society, https://www.cousteau.org/. Jacques Cousteau opened the world’s eyes. They deserved to have a titanium Bear or Calypso.

Photo courtesy Jim Betts www.bettsboats.com

Photo courtesy Jim Betts www.bettsboats.com