How Gdańsk is Reclaiming its Industrial Waterfront

The prosperity of port cities, throughout history, has been closely tied to the ports’ ability to adapt to economic and technological change. As ships got bigger, ports had to keep up. This has often seen the port proper grow apart from the city whose name it bears because the old harbor could no longer accommodate the needs of modernized shipping.

In those European cities located by rivers, port activities have often migrated towards the estuary. The ships headed for the port of Liverpool now berth in docks stretching north of the original Royal Albert dock, along the banks of the river Mersey in a strategic vantage point within the north-west of the U.K., with direct links to major motorway networks.

As port and city have separated, the challenge of what to do with central waterfronts has become pronounced. Urban planners talk of “emerging spatial urgencies” to describe these once-lively centers of trade and their vast structures—the 19th-century redbrick waterfront warehouses in Liverpool; the Clune Park estate in Glasgow; the disused grain silo in Cape Town in South Africa; the former warehouse and distribution center, Hangar 16, in the Old Port of Montreal, in Canada—which have often fallen into disrepair.

As part of my ongoing research into the challenges facing the U.K.’s coastal communities, I have looked at waterfront regeneration projects in European post-industrial regions. The Baltic port city of Gdańsk, in Poland, showcases how cities can return their waterfronts to residents.

It is about restoring the landscape and mitigating the negative ecological impacts associated with former port and industrial land use.

Industrial decline along the Vistula river

Gdańsk is strategically located on the Vistula river and the Baltic sea. In the 19th century, it emerged as a crucial trade hub in Europe. The Prussian authorities invested in shipbuilding and further developing the port.

Most of the industrial growth was concentrated in the Młode Miasto (which translates as “young city”) area, situated close to the river’s mouth, with construction also taking place on Ostrów Island. As the shipyard grew, it served as a repair facility for naval vessels.

After Gdańsk was incorporated into the German empire in 1871, the shipyard became one of the largest in Germany. Most of the older buildings were demolished and spacious production halls were built in their stead.

The industrial sector’s predominance in the communist bloc was evident in the shipyard’s continued growth and the addition of new landscape structures. The giant cranes, still visible today, became a symbol of the city.

The Gdańsk shipyard gained global recognition after the workers’ solidarity protests in 1980, which paved the way for Poland’s exit from the communist bloc. But with the socioeconomic transformation that followed, the institution’s financial status changed drastically. The port declared bankruptcy in 1996.

Transforming Młode Miasto

As part of my research, I compiled a timeline of how Młode Miasto has been regenerated over the past 27 years. This complex, long-term project fits within the wider transformation of what is now known as the Metropolitan Area of Gdańsk Gdynia Sopot. Established in 2011, this is the largest growing urban agglomeration in northern Poland, comprising 58 municipalities.

Integrating this industrial area into the rest of the city has come with challenges. The land was previously hard to access because of physical barriers, including a railway that connected the port to the inland area. In 2018, real possibilities of land development began to be tested, the investor decided to hold a closed urban competition to develop the masterplan.

As a result of the competition, the project proposed by the Danish architectural practice, Henning Larsen, was selected for further work and the company was entrusted with the process of further designing the area due to be completed in 2023.

It involves a web of new plazas, streets and residential and commercial buildings, that will tie the abandoned waterfronts and the histories they tell back into the inland section of the city. The project highlights the imperial basin, the breathtaking views out onto the bay, and the potential in refurbishing the waterfront warehouses.

At the same time, the Polish government is now preparing to submit the former Gdańsk shipyard for inclusion on the UNESCO World Heritage List. Thus, the future of the area is currently the subject of negotiations between conservation authorities and the investor.

From brown to green growth

In December 2019, the European Commission introduced its Green Deal growth strategy, an initiative notable for directly addressing the ecological crisis. It aims to combat what is commonly referred to, by urban planning experts, as “brown growth”. This is urban development that involves carbon emissions, waste production and extractive industries.

By contrast, the EU’s plan seeks to promote “green growth”, which envisions a mutually beneficial relationship between the economy and the environment. Making such a transition from brown to green growth effectively restores the landscape. Making this happen – finding suitable spatial strategies for regenerative socio-ecological systems – is a collective effort.

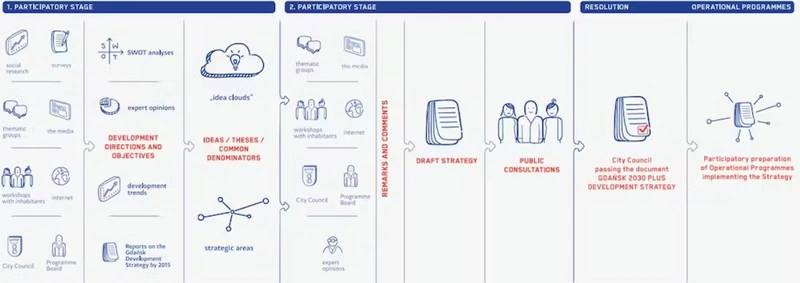

In the Gdańsk proposals, architects are looking at, among other things, ways to improve flood management and promote biodiversity. They are also seeking to involve residents as well as industrial players. The idea of co-designing and co-maintaining the project is crucial. Regeneration here is seen as both a political project of renewal and a bottom-up process of citizen engagement with the urban environment.

Gdańsk’s strategic urban development

Jiayi Jin, CC BY-NC-ND

Jiayi Jin, CC BY-NC-ND

The Młode Miasto development in Gdańsk holds immense significance for other cities with similar histories, from Tyneside in the U.K. to Drammen in Norway. Shifting from brown growth to green growth and restoring the landscape can greatly enhance our urban waterfronts. Giving people a say in how we put the old structures they boast to new uses is vital, if we’re to keep them alive.

The author

Jiayi Jin, Assistant Professor of Architecture, Northumbria University, Newcastle

(Source: The Conversation)