WHOI Investigates Deepwater Horizon Oil Spill

Taking another major step in sleuthing the 2010 Deepwater Horizon oil spill, a research team led by the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI) has determined what chemicals were contained in a deep, hydrocarbon-containing plume at least 22 miles long that WHOI scientists mapped and sampled last summer in the Gulf of Mexico, a residue of the Deepwater Horizon oil spill. Moreover, they have taken a big step in explaining why some chemicals, but not others, made their way into the plume.

The findings, published this week in the online edition of the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, “help explain and shed light on the plume formation and verify much of what we thought about the plume’s composition,” said WHOI chemist Christopher Reddy, lead author of the study. The data “provide compelling evidence” that the oil component of the plume sampled in June 2010 essentially comprised benzene, toluene, ethybenzene, and total xylenes—together, called BTEX—at concentrations of about 70 micrograms per liter, the researchers reported.

The 70 micrograms per liter in the plume, were “significantly higher than background,” Reddy said. “We do not know with certainty the adverse effects it might cause on undersea life.”

WHOI Senior Scientist Judith McDowell said that acute toxicity levels of BTEX are in the range of 5 to 50 milligrams per liter (mg/L) for aquatic organisms—100 to 1,000 times greater than that observed in the plume. Sublethal effects, including neurological impairment, are observed at lower levels, she said. “In most instances the BTEX compounds are volatilized very quickly such that exposure duration is very short,” McDowell said. “The persistence of BTEX at depth poses an interesting question as to the potential effects of these compounds on mid-water organisms.”

A critical component of the study was a one-of-a-kind fluid sample the team collected directly from the broken riser at the Macondo well. To accomplish this, the team used an isobaric gas-tight sampler, a unique piece of equipment developed by WHOI geochemist Jeff Seewald and his colleagues and intended for use collecting fluids from deep-sea hydrothermal vents.

With the gas-tight sampler and other necessary equipment, the lead scientists were shuttled from their active research vessel to a smaller boat and brought to the Ocean Intervention III, operating above the Macondo well. They were then given 12 hours -- working with many unknowns -- to do something never done before. Using an oil industry remotely operated vehicle, they maneuvered the gas-tight sampler to the source of the spill to capture an “end-member” sample of fluid as it exited the riser pipe. No other such sample exists. By analyzing this sample, the scientists were able to determine what was in fluid spewing from the Macondo well before nature had a chance to change it and the exact ratio of gas and oil in the fluid.

“Getting this sample was probably the most dramatic and thrilling thing I have done in my life,” Reddy said.

Using petroleum industry terms, they found a gas-to-oil ratio (GOR) of 1,600 cubic feet of gas per barrel of oil. This value is smaller than other proposed values, Reddy said, suggesting “more oil may have been coming out of the well than other people calculated.”

Analyzing samples from the Macondo well and those they collected from the plume in June 2010 aboard the research vessel Endeavor, the researchers found that BTEX represented about 2 percent of the oil that came out of the well, but “nearly 100 percent of what was in the plume,” Reddy said. “A small, selective group of compounds took a right-hand turn” after exiting the well and formed the 3,000-foot-deep plume, he added. This raises a number of questions, he said, including, “Why are those chemical there in those concentrations? Why are they so abundant in the water?”

The answers have to do with the tendency of those chemicals that “like” to dissolve in water to migrate to the plume, Reddy said. Unlike other substances emanating from the well that degrade or evaporate in the water or at the surface, the compounds in the plume showed little evidence of biodegrading when the researchers examined the plume in June 2010. “[O]il and gas experienced a significant residence time in the water column with no opportunity for the release of volatile species into the atmosphere,” the researchers reported. “Hence water-soluble petroleum compounds dissolved into the water column to a much greater extent than is typically observed for surface spills.”

“We needed to have an ‘end-member’ sample, so that we could compare how nature affected the hydrocarbons as they left the riser pipe,” he said. “So this story is really about, ‘From pipe to plume: what chemicals got off the elevator to the surface and migrated to the plume.’”

The findings have “direct implications for the ecotoxicological impact of plumes,” Reddy said. “Now that we know the compounds were there for a certain time, we need to look at what that would mean to ocean life” Reddy said. “This paves the way to look at any environmental effects,” he said.

The study was funded by the National Science Foundation (NSF) and the U.S. Coast Guard.

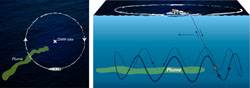

The key to locating and mapping of the plume and the collection of samples from the plume was the use of the mass spectrometer TETHYS integrated into the autonomous underwater vehicle Sentry. Developed by Richard Camilli of WHOI’s Deep Submergence Laboratory, the mass spectrometer is capable of identifying minute quantities of petroleum and other chemical compounds in seawater instantly.

During the June 2010 expedition, Sentry/TETHYS, crisscrossed the plume boundaries continuously 19 times to help determine the trapped plume’s size, shape, and composition. This knowledge of the plume structure guided the team in collecting physical samples using a traditional oceanographic tool, a cable-lowered water sampling system that measures conductivity, temperature, and depth (CTD). The CTD also was instrumented with a TETHYS the mass spectrometer to positively identify areas containing petroleum hydrocarbons.

Guided by the Sentry/TETHYS system, the team collected about 100 samples—a painstaking and rigorous process undertaken under strict natural resource damage assessment (NRDA) protocol and supervision. Since TETHYS is limited in its ability to analyze petroleum hydrocarbons, Reddy said, the best samples were brought back to the land-based laboratories for more sophisticated analyses, which included the help of NOAA.

Dana Yoerger, a WHOI senior scientist and a co-principal investigator on last year’s cruise, added, “We achieved our results because we had a unique combination of scientific and technological skills.”

The current results validated the findings reported with TETHYS, Reddy said.

“Chris’s work demonstrates why federally funded oceanographic research is important to society,” Camilli said. “This paper exemplifies the nearly century-old vision of the National Academy of Sciences in recommending WHOI’s founding. Its publication in PNAS brings the vision full circle.”

Other WHOI researchers who joined Reddy and Camilli in the study were Sean P. Sylva, Karin L. Lamkau, Robert K. Nelson, Catherine A. Carmichael, Cameron P. McIntyre, Judith Fenwick, and Benjamin Van Mooy. Also participating in the study were J. Samuel Arey of the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology at Lausanne and G. Todd Ventura of Oxford University.