Offshore Wind – A Brief History

Happy 80th birthday Maritime Reporter & Engineering News! Eighty years is a significant publishing and business accomplishment!

Birthdays always cause a look back. An 80-year review starts in 1939, the close of one very challenging decade, the start of events still reverberating today. History’s most important history is contained in the last 80 years.

Energy dominated every one of those decades. Consider energy use, say, starting after World War II, from 1950 to 1975. There was power for everything, from seemingly endless sources of oil, gas and coal, and nuclear power was standing by.

Next, recall energy from 1975 to 2000. Not so happy. Most shocking – actual energy shortages, and skyrocketing costs. Just as shocking: social and environmental disasters that could no longer be pushed aside, from Exxon Valdez to ruinous strip mines to Three Mile Island to urban smog.

Now, think of the last 19 years. The Bakken Field. The Permian Basin. Deep-water ocean extraction. And a sophisticated industry ready for any play anywhere, operating at peak scientific and technical prowess.

But there were huge changes in the last 19 years. Oil and gas and coal are no longer the whole story. Renewables – solar and wind – have moved closer to center stage, where they will stay, and increase. Why? Because people like renewables. They don’t want to feel energy guilt. Or more pointedly, guilty about the impacts of energy, from coal sludge to Deepwater Horizon to the climate to monitoring spent nuclear fuel for a thousand years.

Make no mistake, in the next 80 years the world is fortunate that it will have plentiful quantities of oil and gas – responsibly recovered and produced but in the future sipped, not guzzled, in highly efficient engines.

In the next 80 years the world is doubly fortunate that it has the chance to mainstream electricity generation from renewables, again, primarily wind and solar. These aren’t random, disconnected opportunities. Like all progress, these choices are evolutionary, enabled by decisions made, and work started, years ago.

In the spirit of looking back, here’s a brief review of offshore wind and how its development has tracked concurrent to Maritime Reporter’s 80 years of success. Comparably, offshore wind is a newbie (okay, not counting wind power for ships and boats). The first commercial offshore windfarm was built in 1991, in Denmark. The first US project at Block Island, RI, in 2016!

To set a timeline within a modern context this review draws on a fascinating wind energy history developed by the US Department of Energy. On the landside, DOE’s history starts in 1850 when the US Wind Engine Company was established by Daniel Halladay and John Burnham.

In 1890, steel windmill blades were invented, leading to the development of an iconic western symbol.

Important lesson: technological developments, then as now, are critical across all energy advancements.

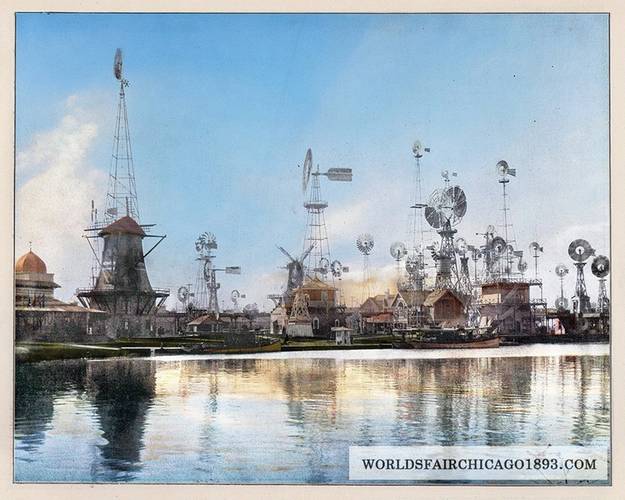

In 1893, fifteen windmill companies showcased wind power at the Chicago World’s Fair. Different models, wood, steel and iron, were adaptable to specific localities and conditions.

After 1893, DOE’s timeline jumps 48 years to 1941, recording that the largest wind turbine of the time delivered 1.25 megawatts to a Vermont utility. But there’s a lesson in that almost half-century gap. America’s electric utilities had developed rapidly, but without wind. Electrical systems, and new demands placed on systems, needed constant, steady power – think coal and hydro. Intermittent wind was fine for remote, singular places, but insufficient for new electrified urban railways, for example.

Then the timeline jumps another 29 years to 1970. It records: “The price of oil skyrockets and so does interest and research in wind turbines and the power they generate.”

Then, events quicken:

-- 1978 – President Carter signed the Public Utility Regulatory Act, requiring companies to buy a certain amount of electricity from renewable energy sources, including wind.

-- 1980 – The first utility-scale wind farms are installed in California.

-- 1981 – NASA scientists Larry Viterna and Bob Corrigan develop “The Viterna Method,” which becomes the most common method used for predicting wind turbine performance, increasing the efficiency of turbine output to this day.

-- 1991 – Denmark – Dong Energy (now Orsted) commissioned Windby, the first offshore wind farm, constructed in water between two and five meters deep. Windby’s 11 turbines provided power for almost 2200 households. It lasted for 25 years, longer than expected, dismantled in 2017. Windby was invaluable as a working laboratory, helping Danish companies to gain expertise, both technically and learning how to export this new offshore business. Perhaps the most important lesson: Windby served as a power station, adding to and complementing an overall electrical system.

-- 1992 – President Bush signed the Energy Policy Act, authorizing a production tax credit of 1.5 cents per kilowatt hour of wind-power-generated electricity and re-establishing a focus on renewable energy use.

-- 1993 – The National Wind Technology Center is established.

-- 2011 – A critical document: DOE’s National Offshore Wind Strategy, a partnership project with the Department of the Interior. The goal: to reduce the cost of energy through technology development and reducing deployment timelines.

Gary Norton is a Senior Renewable Energy Technologies Advisor within DOE’s Wind Energy Technologies Office. Norton was a contributing author of the 2011 Strategy and the 2016 Strategy update. He was asked: How is offshore wind doing – moving too slowly or where we need to be?

“I think we’re doing really well,” Norton replied. He cited interagency collaboration as particularly important and productive, with DOE focusing on technical advances that would lower the cost of offshore wind power while the Bureau of Ocean Energy Management (BOEM) worked on best ways to speed up the complex regulatory process for ocean-based projects.

CutGary Norton

CutGary Norton

Gary Norton, Sr. Renewable Energy Technologies Advisor, U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy, Wind Energy Technologies Office/Water Power Technologies Office

Norton said the original projections in the 2011 Strategy were “pretty aspirational.” Now, however, “things are really taking off in many states with many project developers and committed financial support.” When this work started, he noted, uncertainty dominated. “Now it’s happening,” he said, referencing, for example, the huge increases in site valuations. “In Massachusetts,” Norton point out, “recent BOEM wind energy area lease bids jumped to $135 million, up from $42 million a few years earlier and just $1.5 million in an earlier round of bidding.”

Another critical Strategy outcome: the National Research and Development Consortium, currently comprised of most major offshore wind developers and four Atlantic coast state agencies from Massachusetts to Virginia. In 2018, DOE chose the New York State Energy Research and Development Authority (NYERDA) as consortium administrator. DOE contributed $20.5 million for competitively solicited R&D projects, and NYSERDA matched that amount.

Finally, Norton emphasized the importance of DOE’s economic analyses pertaining to offshore wind and how it can best fit into the overall energy marketplace, maximizing its value. Also critical: the emerging, and increasing, revaluation of many east coast ports as they prepare and position themselves to play leading roles in the maritime logistics required to build out an entirely new energy industry.

2013 – A critical project: construction of the first floating offshore wind turbine connected to the grid. This was a DOE partnership with the University of Maine, deploying a 1:8 scale, 20-kw concrete-composite floating platform wind turbine--the first in the world. This project will inform design and construction of two full-scale floating offshore wind turbines, work underway now, set for completion in 2021. The project utilizes patented VolturnUS platform technology, a floating concrete hull that can support wind turbines in water depths of 45 meters or more (recall Windby’s 2-5 meter depth).

Habib Dagher, PhD, PE is the Executive Director at the University of Maine’s Advanced Structures and Composites Center.

Dagher explained that Maine has been buffeted by high energy costs. Maine’s initial interest in offshore wind started with a big question: How much power do we need for everything from heat pumps to electric vehicles? In Maine, offshore wind has an estimated potential of 160 gigawatts. Dagher said the entire state uses about 2.4 GW. Just 3% of potential ocean wind energy would meet all of ME’s needs!

Deep water, though, prevents fixed-bottom turbines. Hence the research into floating technology. UofM focused on key problems: stability, storms, design. Dagher said the scaled-down model passed all tests, from its grid interconnection to withstanding a 500-year storm.

But the biggest payoff? Modeling. Dagher said UofM energy models will allow easier, faster and more accurate evaluations and assessments for matching project site with equipment, materials and positioning. All of that means cheaper energy from offshore wind.

-- 2016 – Block Island Wind Farm in Rhode Island, starts up, the first commercial offshore wind project in the US. It’s relatively small – 30 megawatts, a project developed by Deepwater Wind.

-- 2018 – DOE reports (2017 data) that the U.S. has a total of 25,434 MW of offshore wind energy in the pipeline, with projects in development in New York, New Jersey, Massachusetts and Virginia.

Globally, (2017 data) 3,387 MW of offshore wind capacity was commissioned, resulting in a cumulative installed global capacity of 16.3 GW. The United Kingdom is the largest offshore wind market with 5,824 MW of cumulative installed capacity, followed by Germany (4,667 MW), China (1,823 MW), Denmark (1,399 MW), and the Netherlands (1,124 MW).

DOE reports that globally, auction prices continue to fall. In 2017, developers placed four bids that were termed as “zero-subsidy.”