Pirate Alley

Book offers a commanding view of piracy at sea: Naval forces, high freeboard, speed, and armed guards contribute to reduced success by Somali pirates, but the problem will not go away

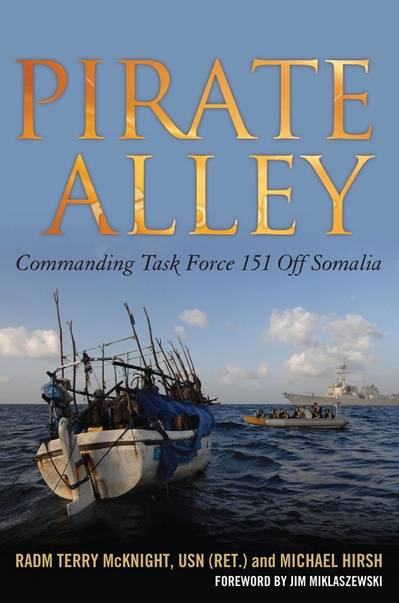

Even with a multi-national flotilla of warships, armed security guards on merchant ships, and phalanxes of lawyers making policy and negotiating ransoms, seemingly unsophisticated Somalis and their small, simple skiffs still attack ships on the high seas and hold seafarers, ships and cargos for ever-growing sums of money. These crimes have sparked an international naval response to protect ships, cargos and crew, particularly in the Gulf of Aden and Indian Ocean, known as “Pirate Alley.”

Rear Adm. Terry McKnight, a retired naval officer, had a front row seat in the effort to deter and defend against piracy on the high seas. McKnight, who with Michael Hirsh wrote Pirate Alley – Commanding Task Force 151 Off Somalia, published by the Naval institute Press, knows about that naval response. He stood up Combined Task Force (CTF) 151 in January 2009, as part of the Combined Maritime Force, headquartered in Bahrain. He says the naval presence has made a difference. “It has been with us for many, many years. As long as ships go to sea . . . there will be piracy.”

“I wanted to tell the story about piracy ‘from the sea,’” McKnight says. “There has been tons written on the issue from some very smart people, but none of them had firsthand knowledge at sea. I also wanted to tell the story about our great service members who do some really special things at sea.”

The subject of piracy, especially with regards to Somalia, is very complex. There can be no solution until a stable government exists that can enforce the law in Somalia. Until then, the pirate leaders can send out their “pirate action groups,” or PAGs, from their bases ashore with impunity. McKnight also says that the public has some real misconceptions about piracy. “They amount to small numbers in the big world economy, so why should it matter to the average citizen?”

But it does, he says, because the free flow of ocean shipping is critical to our global economy.

When the situation began to get world-wide attention, CTF 151 was established. Today, there are several naval operations ongoing simultaneously, to include CTF 151, which McKnight commanded, under the guidance of the Combined Maritime Force, located at the U.S. Naval Central Command in Bahrain. Then there is the European Union’s EU NAVFOR Operational Atalanta, protecting the World Food Program’s shipments to Somalia. There is also a NATO Operation Ocean Shield task force, working with the NATO Shipping Centre in Northwoods, UK. There are independent deployers from countries like India, Russia and China, as well. They might not be part of a coalition, but McKnight says cooperation, information sharing and professionalism of all the participating navies was and remains excellent.

When CTF 151 was established, the task force was to protect merchant ships, and catch pirates. But there was no real plan to start out. They were, in a matter of speaking, making it up as they went along.

The big problem was made bigger by the distances involved. The Gulf of Aden is over 1.1 million square miles of ocean—three times the size of the Gulf of Mexico. The number of ships and aircraft assigned to the various counter-piracy naval operations changes regularly.

“With over 2,400 miles of coastline it would be hard to blockade the entire coast,” he says. “You could consider attacking the pirate camps, but the pirates do not wear uniforms and you risk killing innocent civilians. . You could search all the dhows and skiffs leaving the shore, but there are not enough naval forces to do the job.”

The naval forces couldn’t be everywhere. If a reported attack was not far from a warship, they were generally successful in getting a helo or ship to the merchant within 30 minutes. “We used the ‘golden rule,’ if we could get a ship or helo over the merchant ship being attacked, we had a pretty good chance of preventing the ship from being ending up in a pirate camp!”

“Even the so-called ‘thousand ship navy’ would insufficient to cover the region,” McKnight says. “It’s like a dozen police cars patrolling the entire United States.”

“Nobody was prepared to catch pirates. The MOU (memorandum of understanding) with Kenya (where they agreed to accept and prosecute those who violated international law by committing acts of piracy) was not signed until the end of Jan 2009 and procedures worked out with AFRICOM on how to get the captured pirates to Kenya.

While combatants with their speed and firepower (not to mention aircraft) were formidable pirate-chasers, among the most effective naval platforms for counter-piracy operations are the ships with lots of room inside to detain pirates if they were captured. The Danish Absalon-class of flexible support ship and Royal Fleet Auxiliary Fort Victoria, with their voluminous interior space, could be used to detain captured suspects until they knew where to send them.

McKnight said land-based maritime patrol aircraft, such as the P-3 Orions operating from Djibouti and the Seychelles, became a force multiplier. “I only wish we had more on-station time.”

Even in the few short years since McKnight commanded CTF 151, the ability to fight pirates, as well as the tactics and capabilities of the pirates themselves, has evolved.

The shipping community has also responded. McKnight says the industry’s collective “Best Management Practices” (BMP) work. It requires an investment in training and physical security, but ship owners and operators must make the commitment. What ship owners generally can’t change is speed and free board—the distance from the water to the main deck. “Any ship transiting the area that has a low free board and speed restrictions below 18 knots needs to consider hiring a security team for extra protection.”

Several years ago, the idea of private security companies protecting ships was frowned upon. Today many ships have armed guards aboard. “Private security teams are one of the major reasons the tide on piracy is turning. As of today, not a single ship that has hired a security team has been taken by the pirates. However, it comes at a cost. These teams are expensive. It cost approximately $50,000 for the transit through the Gulf of Aden. We are all are paying for that cost where we shop.”

Still some countries will not allow these teams to embark and disembark with weapons, he says. “So that means some vessels must make a quick stop at another port to disembark. Most of the security firms are hiring former Special Forces members. They know how to shoot, but do they understand hostile intent or rules of engagement? If you hire a team – your insurance cost goes up. Again, the consumer ends up paying.”

Also, he says, some merchants have decided to turn off AIS during their transit. AIS is the “automated information system” that functions much like IFF on planes. It sends out a signal with the name of the ship, location, course and speed and other information. This helps the good guys know where you are, and turning it off, he says is not recommended. “The pirates don't really have the ability to track merchant ships in the Gulf of Aden and AIS assists the naval force keep a "COP" (common operating picture) of all merchant vessels in the area.”

In addition to sharing his own eye-witness observations, he calls upon others with first-hand knowledge of what was happening out there.

Capt. Mark Genung and his crew aboard USS Vella Gulf stood by the M/V Faina while it was held by Somali pirates. During the ordeal, the Faina’s master died. When liberated, the first mate—who had become the master—expressed gratitude to the Vella Gulf crew. “Our liberation would not have been possible without your presence,” said Viktor Nikolsky. “Our lives were spared because you were here to protect us.”

McKnight credits the pirates with adapting their tactics and expanding their area of operations, making it difficult to find them and stop them altogether. And, he readily admits that the fact that the pirates operate from a place that is not governed by the rule of law makes it impossible to hold the government of Somali accountable to wipe out the pirate bases.

Pirate Alley: Commanding Task Force 151 Off Somalia

by RADM Terry McKnight, USN (Ret.) and Michael Hirsh

Publication date: 15 October 2012

272 pp., 38 photos, 1 map. Hardcover

ISBN: 978-1-61251-134-4 /List price: $29.95

(eBook edition also available)

(As published in the December 2012 edition of Maritime Reporter - www.marinelink.com)