Waterways Commerce Cutter: It's Time for an Upgrade

In the last week of April, with little fanfare, the U.S. Coast Guard released a much-anticipated opportunity to build up to 27 Waterways Commerce Cutters. After the detailed design and construction contract is awarded in Spring of 2022, a lucky shipbuilder will begin replacing the Coast Guard’s eclectic fleet of 18 venerable river buoy tenders (WLR) and 13 inland construction tenders (WLIC).

The Coast Guard’s inland waterways maintenance fleet has been ignored for far too long. It is about time America tended to the low-profile Coast Guard vessels that spend their days tending some 28,200 marine aids on America’s 12,000 miles of inland waterways. With an average age of over 55 years, the riverine workboat fleet has sprawled into nine separate ship classes, ranging from the Coast Guard’s oldest cutter, the 77 year old Inland Construction Tender and Coast Guard “Queen of the Fleet” USCGC Simlax (WLIC-315) to the two youngest members of the riverine fleet, the 30-year old River Buoy Tenders USCGC Kankakee (WLR-75500) and Greenbrier (WLR-75501).

The lack of interest is understandable. At best, buoy tenders are utilitarian craft, overshadowed by the Coast Guard’s more dashing “white-hulled” cutters and patrol boats. Inland buoy and construction tenders, plying America’s inland waterways, are even less exciting. They trundle about in quiet waters, setting buoys, clearing brush from navigation signals, removing wreckage, and handling various construction tasks. But the Coast Guard’s often unnoticed contribution to waterways maintenance is enormously important in keeping America’s maritime transportation system open, functional and trouble-free.

The new ships—an initial tranche of 16 river buoy tenders and 11 inland construction tenders—are expected to enter service sometime between 2025 and 2030, arriving at a fascinating period of economic and technical change on American waterways. Over the new tender’s expected “minimum of 30 years” design service life, the Waterways Commerce Cutters are likely to preside over a waterfront renaissance, supporting a far more intensive national utilization of America’s first real freeways than most expect.

There is a lot to do, and, frankly, the winning shipyard could immediately start making a case to grow the program of record. The Coast Guard’s request may be undersized for the coming need. The Coast Guard, of course, has rightly focused on the $5.4 trillion dollars America’s maritime transportation system provides the U.S. economy today. But the Service might have understated the tender’s ultimate business case.

Such a suggestion may be contrary to popular opinion. Some maritime innovators consider old-school navigational aids obsolete, a dying maritime feature ripe for replacement by “virtual” buoys or other fancy electronic traffic control schemes. That’s fine, but the old-fashioned “dumb” steel buoy isn’t going away anytime soon, and, with more and more river traffic coming online, an active Coast Guard presence will still be required on the rivers. A refreshed and reinvigorated Waterways Commerce Cutter fleet can help get the Coast Guard where it needs to be as the inland waterways transform.

America’s inland waterways are already changing. Riverine passenger traffic is increasing and inland waterway passenger volume may grow far faster than expected. Take Viking Cruise Lines. The company is known for rapid expansion into new markets—Viking entered the ocean cruise market in 2015 and, today, it expects to have 16 ships in service in the next few years. On the riverine side, over the past eight years, Viking has commissioned more than 60 river cruisers worldwide.

It will soon be America’s turn. Viking’s first river cruiser, the Viking Mississippi, is set to be a big ship, mustering 193 staterooms and a guest capacity of 386. And Viking is not alone. American Cruise Lines is in the midst of bringing a fleet of at least four modern river cruisers online, joining American Queen Steamboat Company’s four majestic riverboats. If these big river cruisers take off, they will drive waterfront development, force operational changes on the waterways and, at a minimum, demand top-tier navigational aid support.

The wider shipbuilding community may not fully understand that the Coast Guard’s new inland fleet will—almost by default—offer more utility than the legacy tenders. The aged and infirm fleet is already an under-appreciated provider of emergency response services—according to the Coast Guard Commandant, Admiral Karl L. Schultz, “inland cutters and Heartland Sectors responded to over 1,100 marine incidents in 2020,” responding to “marine casualties, oil discharges, hazardous material releases and various security threats.” As the modern platforms will be more reliable and capable, an array of emergency response duties will open to the Coast Guard’s new inland waterway buoy and construction tenders.

That’s good. America’s rivers traverse some of the least-prepared cities and potentially highest-risk areas for accidents and other contingencies in the United States. If any one of the planned big new river cruise boats get into trouble, riverside first-responders will be hard-pressed to handle hundreds of passengers and crew. They’ll need help. And then, as the acute danger passes, the Coast Guard will likely be called to manage or monitor what will be a complex multiagency recovery, investigation and salvage effort.

On the rivers, the potential for industrial accidents is always present, and, as riverside development and passenger traffic increases, timely river emergency response and command-and-control platforms will likely be in even greater demand than they are today.

The likely need is not just focused on conventional short-term emergency response, either. On the rivers, emergencies are often slow-evolving things, where disaster hangs in the balance for days or even weeks. In one example from 2016, a barge carrying 2,400 tons of anhydrous ammonia ran aground in the Quad Cities area, and authorities needed ten days to secure, refloat and transfer the dangerous cargo. River and coastal responders know that complex contingencies with dangerous cargoes can become tense, weeks-long affairs.

For that sort of work, the new inland cutters, which will be expected to provide up to 11 days of accommodations and habitability for around 17 to 19 crew members, might be perfect assets for situations where on-the-spot, command and control assets are needed for a period of time. To that end, cutter endurance is a highly rated evaluation factor, and a means to improve cutter endurance in a pinch might be an interesting differentiator for responding shipyards.

It might also be worthwhile for innovative shipyards to consider how the new tenders might support other State, Local and Department of Homeland Security components in an emergency, and, potentially, integrate with the Coast Guard’s hazardous materials experts at the National Strike Team, commandos in the Maritime Security Response Team or other special Coast Guard assets. The Coast Guard already indicates the platforms should have strong multi-agency communications capabilities, and there are other features out there that a crafty builder could propose to gain an edge on the competition.

Floods, storms and natural disasters are all areas where a refreshed inland cutter fleet can shine. Category 4 Hurricane Laura forced the Coast Guard to repair or replace 80 navigation aids, but it also created toxic dangers as well. During the hurricane response, twenty of thirty-one spill response requests to the National Response Center were detailed to the USCG for action. Disasters can be seasonal or unique. Annual spring floods are a chronic challenge, and, on the other hand, government experts believe that the New Madrid fault, which stretches roughly from the river bottoms of Memphis, Tennessee to Paducah, Kentucky, has a 25 to 40% chance of generating a magnitude 6 or greater earthquake over the next 50 years.

All of these disasters require—or would require—substantial waterway navigation aid recovery work. But the cutters, already optimally positioned throughout the inland waterway system, will still need to get to where they are needed. It may well be why the Coast Guard has emphasized mobility, highlighting both speed and draft as important performance requirements.

Finally, the future inland tender fleet will be serving during a period of substantial technological change. As a decidedly “low-tech” platform, the Coast Guard is shying away from high-tech baubles and wants bidders to offer only robust, solid-state gear. But that does not mean shipbuilders should forgo thinking about the future.

The vast potential for unmanned platforms is already obvious, and, since buoys are, for the most part, unmanned platforms that simply lack engines, these tenders may have a real future in bringing unmanned craft to America’s inland waterways. Some guesses as to how those platforms-of-the-future may integrate with the future waterways commerce cutter fleet may be an interesting way for the Coast Guard to keep the Waterways Commerce Cutter fleet relevant in the future, blending exciting new technologies with the tough, old-school task of keeping America’s waterways open and American commerce going unvexed to the sea.

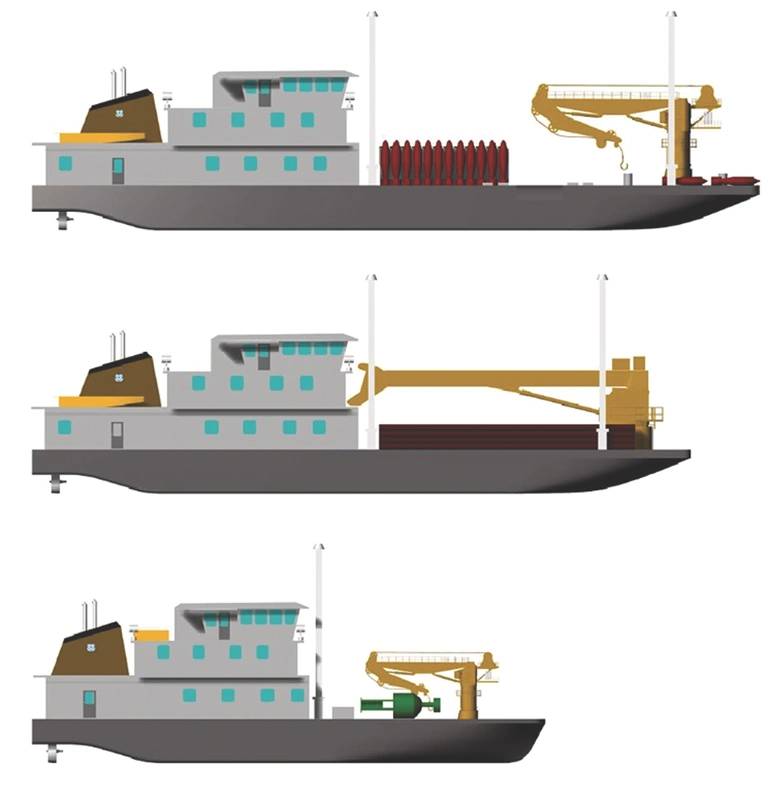

Coast Guard illustrations showing indicative (i.e., notional) designs for the WLR (top), WLIC (middle) and WLI (bottom). (Image: U.S. Coast Guard)

Coast Guard illustrations showing indicative (i.e., notional) designs for the WLR (top), WLIC (middle) and WLI (bottom). (Image: U.S. Coast Guard)