Late again, but who is to blame?

With the peak season now in full flow, cargo rollovers are more likely, but ocean carriers are not the only party to blame.

Cargo no-shows and phantom bookings are still a major headache for ocean carriers, particularly during the peak season. Whilst cargo booked from Asia to Europe was being rolled onto following vessels at the beginning of July due to a combination of unusual circumstances (see last week’s analysis of the Asia-North Europe tradelane for more details), some ships still sailed light due to last minute booking cancellations.

It will happen again as, according to one cynical carrier, roll-overs are only caused by the “usual” level of cargo no-shows being less than normal, and late cargo delivery cut-offs have become a highly competitive feature of most carriers’ sales strategy. Phantom bookings just add to the problem, being the work of forwarders that foresee a strong market, and try to reserve more than enough space for it in the hope of capturing new customers that may eventually be caught short.

The point underlines a continuing inefficiency of deep-sea supply chains which, if resolved, would help counteract the negative side of slow steaming. For cargo to be delivered at destination on time, it has to be shipped on time. The problem is not new, but ocean carriers’ attempts to minimize the damage by imposing heavy penalties still appears ineffectual.

Quantifying this is not easy, as bookings failing to arrive on time can be due to a number of understandable reasons, including delays with intermodal transport, regulatory problems, unexpected production difficulties, container equipment shortages, and feeder vessel schedule failures. If a connecting barge, train or feeder vessel gets held up somewhere, a lot of allocated deep-sea vessel space can end up not being used at the last minute, and, as ocean carriers know only too well, 100% schedule integrity is often destroyed through the mistakes of others.

This makes the strict enforcement of late cancellations fees difficult, particularly as sorting out fact from fiction can be laborious. It is also still a ‘buyer’s market, so much depends on everyone applying similar rules, which is far from the case. Some carriers continue to rely on other less obvious ways of minimizing the damage of last minute booking cancellations, including the blacklisting of repeated offenders.

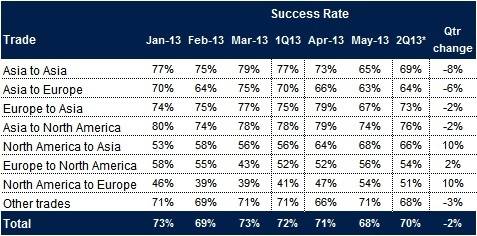

Table 1 shows that a remarkable 29% of cargo booked in 1Q13 failed to be shipped on time, although this includes delays caused by deep-sea vessels not arriving for loading punctually. This was even worse than the 27% of ships that failed to arrive at destination on time.

For the purposes of this exercise, a shipment is deemed to have been a success when the difference between the estimated date of shipment stated in the original booking confirmation at the first load port and the corresponding actual departure date is within a day. This means that the cargo can still be shipped on the requested vessel, only more than a day late for loading.

On Time Shipment of Cargo

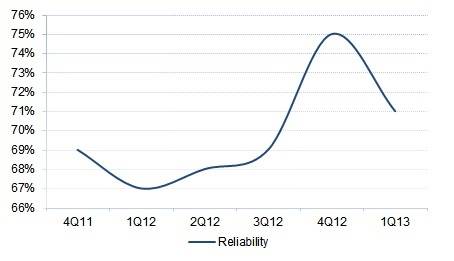

The proportion that failed to be shipped on time was 4% more than in the previous quarter, demonstrating that much more remains to be done. There has been a gradual improvement since 4Q 11, however, which coincides with the time that Maersk started beating the drum over the need for greater penalties for late delivery of bookings, and the strict application of the rules (see graph below).

Since then, ocean carriers have been rolling out penalties for late cargo delivery on a regional basis. For example, at the beginning of this year Maersk’s network of late delivery charges reached Australia, where a penalty fee of $100 per dry container for booking cancellations made within seven days of ETA was introduced. OOCL’s fee of GBP£250 per container for cancellation requests received less than five working days before arrival of vessel reached the UK on 19 March 2013.

According to Maersk, it still received approximately 2,700 ghost bookings in all tradelanes in the first 22 weeks of this year, totaling around 12,000 x 40ft, but this was at least 50% less than five years earlier. However, instead of being mainly an Asian problem, it has become more global.

At the recent Retail Supply Chain conference in London, it was stressed that the big focus for retailers now is to improve “availability” of products on the shelf or in the store, thereby minimizing lost sales. As slow steaming seems set to stay, or even get worse, this means that further efficiencies need to be wrung out of supply chains. Further minimizing no-shows and phantom bookings would consequently be a good start.

Drewry believes Carriers are struggling to collect booking cancellation penalties from shippers due to too much focus on freight rate levels instead of value added services.

Source: Drewry

ciw.drewry.co.uk