On Ballast Water, Time is Running Out

The MEPC 65 resolution was meant to help facilitate the long-awaited ratification of the IMO’s Ballast Water Management (BWM) Convention. But has it actually done more harm than good? The ballast water treatment supplier sector and environmental lobby are unequivocal in their assessment. Alan Johnstone reports.

“My initial reaction was guarded, but hopeful,” confesses Lars Erik Mangset of the WWF, when asked about his response to the MEPC 65 draft resolution on ballast water in May.

“Retrofitting existing vessels with ballast water treatment (BWT) systems was always one of the key hurdles on the road to ratification of the BWM convention, so if this was addressing that concern for shipowners then we could accept it. With this resolution we thought, ‘right, there’s no more excuses’.”

It appears he’s no longer quite as hopeful, as he adds with a sigh: “But what has happened since? You tell me.”

That’s a challenge that Tore Andersen, the CEO of ballast water treatment (BWT) system specialist Optimarin, is keen to take on.

“On the order front, very little,” he admits candidly, “especially with regards to retrofitting. But there is movement in the sector – movement of the wrong kind. And the MEPC 65 resolution, which is yet another chapter in a long running saga defined by on-going uncertainty and frustration, has to take some responsibility for that.”

The Long Road to Ratification

The long running saga Andersen references is the glacial progress of the IMO’s Ballast Water Convention, introduced back in 2004. And, with only 37 countries representing 30.32% of the world’s tonnage having ratified the convention to date (35% is required), it looks like it may run on for some time yet.

As Mangset points out, MEPC 65 was meant to change this, effectively relaxing the deadlines for the installation of BWT systems (recommending that ships built prior to ratification need not install systems before their first renewal survey after that ratification).

When the resolution is passed in November it will give shipowners, in some cases, years of previously unexpected breathing space to plan retrofit installations across their global fleets.

“That’s far from ideal,” Mangset states, “but it is manageable if it’s coupled with concerted political action to convince some of the remaining major flag states, like Panama, to climb on-board the ratification process. It needs to be a balancing act.”

Unfortunately, as he sees it, the scales have been tipped very heavily to one side: “There’s been no action,” he stresses, “which sends out entirely the wrong message to the industry.”

Something that Andersen and his peers in the BWT sector can attest to.

The Threat of Inaction

“There’s more and more of a ‘well, let’s just wait and see what happens’ mentality, and that is beginning to undermine our industry,” notes the Optimarin boss.

To consolidate this point, Andersen nods in the direction of Desmi. The pump solutions specialist announced in mid-September that it was to cease offering customers its Desmi Ocean Guard BWT system due to market “uncertainty” and the aforementioned “wait and see attitude.” An official release from the firm said that it would now concentrate its efforts on “the sale of our other products focusing on green technologies” but expects to return to ballast water “as the market matures.”

“That is a real shame,” Andersen states, “but at least a business of their nature has other divisions and technology to fall back on. BWT specialists like ourselves – remember we’ve been working on this since 1995 and installed the world’s first commercial BWT system in 2000 – don’t have that. This is our exclusive focus.”

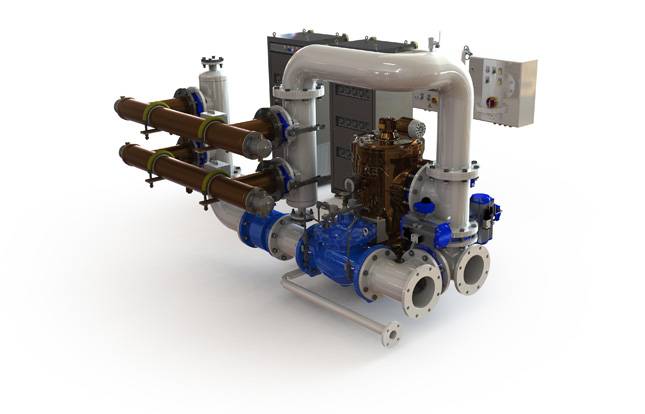

Optimarin has invested what Andersen calls “considerable sums” in developing its simple, reliable and easy to install filtration and UV irradiation system, emerging as a leader for vessels up to approximately 60,000dwt. It boast sconfirmed orders for 250 ships and has installed around 100 systems, with further “considerable sums” spent on ensuring that these units are all DNV, IMO and US Coast Guard approved. But Andersen said, “It is worrying, but more than anything else it’s hugely disappointing.”

A sentiment shared by Mangset.

“Five or six years ago, the main argument against ratifying the convention was the lack of technology on the market. Well that is no longer the case; there is now a good commercial environment, with a variety of solutions (an estimated 40 systems are now approved by the IMO).

“However, as we’re seeing now, the longer the ratification process takes, the greater the sense of uncertainty and the greater the threat to those suppliers. This puts the further technological development of solutions at risk, while the withdrawal of suppliers weakens the sector and provides less options for shipowners, who may therefore delay their decision making even further.”

This, he states, is not what the industry needs… and as for the environment…

Silent Invasion

The damage to the sector is one thing, the catastrophic on-going impact of untreated ballast water on marine ecosystems around the world another. Mangset calls ballast water “the second biggest threat to global biodiversity after climate change.”

He explains: “Each year about 10 billion tons of ballast water is transported around the world, with around 7,000 marine species carried every single day in ballast water tanks.

“These species, often aggressive and fast-producing, can out compete native flora and fauna when deposited in untreated ballast. Back in 2009 we conducted a study that found that 84% of the world’s 232 marine eco-regions had reported findings of invasive species, with international shipping being the primary pathway for pest organisms. The damage being inflicted on a daily basis, right now, is just breath-taking.”

Mangset says that the same report found that between 2004 and 2009 the spread of invasive species had resulted in global economic losses of around $50 billion (2004 to 2009). Losses came not only from depleted fish stocks, but also from damage to local environments, infrastructure and industry (the Zebra Mussel is a case in point, with the Eastern European invader causing havoc in the US by blocking up water inlet pipes for coal-fired power stations, costing the energy industry tens of millions of USD every year).

Need for a New Impetus

“But despite this colossal damage,” Andersen says, as he moves onto the green cause, “there is no real political impetus to ratify the BWM convention and finally stop these invisible invaders. Many of the remaining major flag states, who could push the convention across that 35% boundary overnight, are quite simply not taking responsibility and signing up.”

In the face of the never-ending delays, Andersen says that more could be done to protect both the environment and the shipowners that are forward-thinking enough to invest in BWT systems pre-ratification. He believes that introducing ‘grandfather clauses’ is one way to stimulate activity.

“Grandfather clauses that protect the investments of shipowners would really help,” he notes. “Then, if regulations and standards were to change and become more exacting, the ships that were already fitted with BWT systems would be exempt. That would tackle the sense of uncertainty and encourage shipowners to take responsibility for their ballast water today.

“With each further day of procrastination the damage amplifies – to the environment and the industry. It’s the invasive species that should be at threat by now, not the ballast water industry itself.”

(As published in the November 2013 edition of Maritime Reporter & Engineering News - www.marinelink.com)