BIMCO: US Soya Bean Exports - Up or Down?

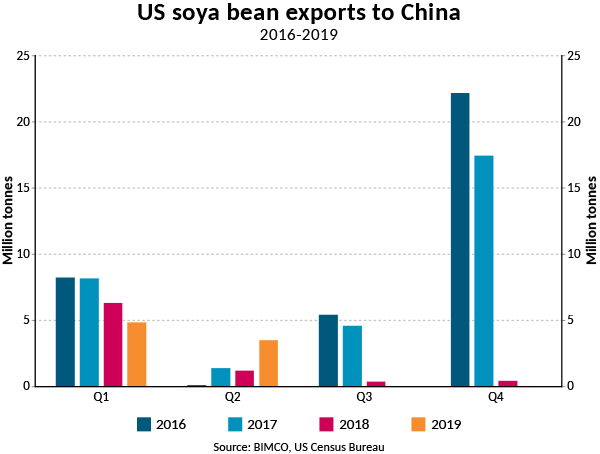

The trade war has brought increased attention to the soya bean trade between the US and China with 2019 offering conflicting narratives. On one hand, soya bean exports to China in the first six months of 2019 are up 10.9% compared with the first half of 2018, while on the other, exports to China in the 2018/2019 marketing year are down 68.7%.

With the 2019/2020 marketing year now just round the corner, this trade is unlikely to return to pre-trade war levels. The combined effects of a worsening relationship between the nations as well as a smaller US soya bean crop, leads to fears that the US to China soya bean trade may never fully recover.

The decline over the marketing year is what counts

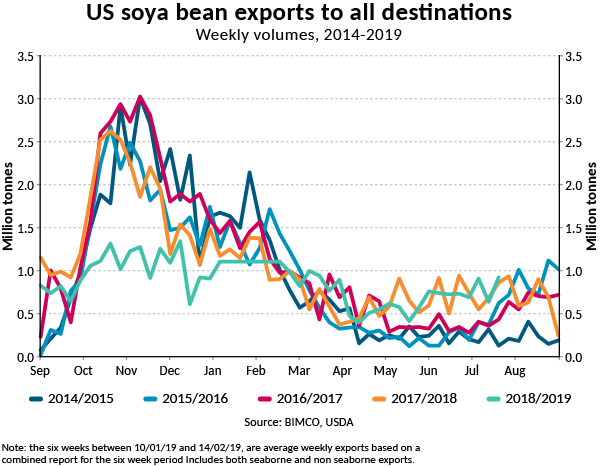

The 68.7% decline over the marketing year best represents how the trade war has impacted farmers and shipowners alike. This is because, traditionally, the US exports most of its soya beans between September and December. For example in 2017, of total US soya bean exports, 72% were sent to China, more than half of which were exported during the last four months of the year: 17.5 million tonnes between September and December compared to 14.3 million between January and August.

Because of the distinct seasonality of these exports, using a growth figure which only covers the off-season does not reflect the full picture.

Growth rate overstates underlying volume growth

Furthermore, the 10.9% growth in the first half of 2019 compared to the same period in 2018 sounds more positive than the reality, with the growth in volume terms amounting to only 822,720 tonnes in extra exports to China, or just 11 additional panamax loads (75,000 tonnes). Total soya bean exports to China in the first six months of 2019 amount to 8.4 million tonnes, most of which were reportedly goodwill purchases by the Chinese in an effort to move trade talks forward. The year-on-year is driven by higher exports in Q2, and in particular during May and June. At the end of Q1, exports were down 23.7%.

“The growth figures have to include exports in September to December for them to paint a true picture of the developments in this trade. That is why BIMCO uses the marketing year, which for the US soya bean exports starts in September, to gain an understanding of the developments,” says Peter Sand, BIMCO’s Chief Shipping Analyst, adding:

“The decline in exports to China during the first ten months of the 2018/2019 marketing season reveals the impact of the tariffs that Chinese imports of US soya beans have been subject to since July 2018. Shipowners had become accustomed to high volumes being shipping during the final four months of the year, and the low volume growth so far this year in no way makes up for the volumes lost during the last four months of 2018.”

China remains the largest destination for US soya bean exports

The increase in exports to China during the first half of 2019 can also be seen in the marketing year growth figure, with the higher exports reducing the still dramatic fall in volumes. At the end of 2018, with the traditional peak months for US soya bean exports over, exports to China were down 98.3%. Since then, the fall in total exports to China over the 2018/2019 marketing year has decreased to 68.7%.

As of the end of June, the equivalent of 251 Panamax loads of soya bean exports to China have been lost in the 2018/2019 marketing year. The share of exports going to China has nosedived, from 55.2% in the first ten months of the 2017/2018 marketing season to 17.3% in the same period of the 2018/2019 season.

Despite this, China has maintained its position as the largest destination for US soya bean exports, although its lead has shrunk considerably. In the first ten months of this season, China imported 8.6 million tonnes compared to second placed Mexico’s 4 million tonnes. Last season, the US sent 25 million more tonnes of soya beans to China than it did to Mexico in the first ten months of the season.

South and Central America as well as the EU stepped up their imports of US soya beans

Although total exports have fallen 23.6% in the first ten months of the 2018/2019 marketing season, exports to all destinations other than China have risen 31.9% or 7.1 million tonnes to reach 29.3 million tonnes.

In particular the EU and South and Central America have increased their purchases of US soya beans, respectively growing 71.1% and 66% compared to the first ten months of last season. Several countries stand out in having massively grown their imports of soya beans from the US, such as Argentina and Spain whose imports have grown enormously; 6,297.3% to reach 1.9 million tonnes and 2620.5% to reach 1.7 million tonnes respectively. In the first ten months of the 2017/2018 marketing season, Spain imported 630,800 tonnes and Argentina only 29,300 tonnes.

What’s next for this trade?

The start of the next marketing season is now less than a month away and unlikely to signal a return to what farmers and shipowners have known in years before the trade war. On top of a smaller crop in the US as a result of poor weather, as well as farmers being hesitant to plant soya beans without assurances that they would be bought in China, further escalation of the trade war brings bad news to shipowners used to having their ships sailing soya beans between the US and China. On top of this, the large scale culling of pigs in China in a response to African swine fever will markedly reduce China’s demand for soya beans for years to come.

One of China’s immediate responses to the latest trade war escalatation was to announce that it would stop buying US agricultural goods, and thereby soya beans. At the end of July, the US announced 10% tariffs on USD 300 billion worth of imports from China, meaning that all Chinese imports to the US are now directly involved in the trade war.

“With a worsening relationship between the US and China, this trade is unlikely to return to previous levels any time soon, if it ever does. For any hope of the trade returning to previous levels, a trade agreement will need to be reached between the nations, and even then, once a market has disappeared, there is no guarantee that it will return,” says Peter Sand.