Chinese Demand Keeping the Dry Bulk Market Going -BIMCO

An impressive recovery in Chinese dry bulk imports has protected the industry from the effects of falling demand in the rest of the world. High deliveries and low contracting have left the orderbook at multi-year lows, but – with the poor outlook – the current influx of new dry bulk ships orders is not what is needed.

Demand drivers and freight rates

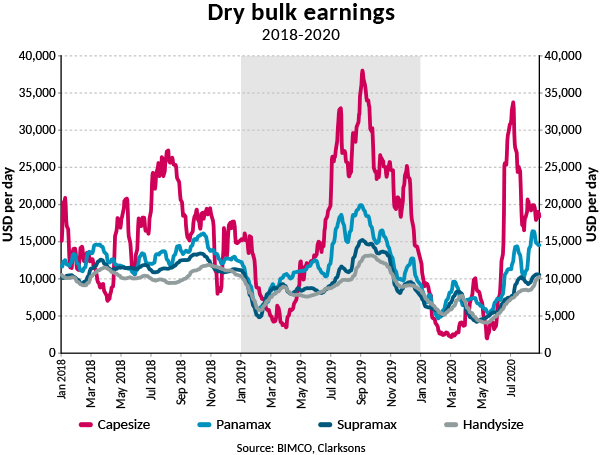

The biggest story in the dry bulk industry in recent months has been the strength of the recovery in major Chinese imports. These are up across the board, breaking previous records, not just for monthly imports, but also accumulated over the first seven months of the year. The Chinese recovery has been strong enough to make up for lower activity in the rest of the world, with all ship sizes above their break-even levels.

Capesize earnings rose quickly in late June, to reach $33,760 per day on July 7. The high Chinese imports led to congestion at many of its ports, temporarily lowering the number of available ships. Since then, rates have fallen to a more sustainable level, averaging around $19,400 per day in August.

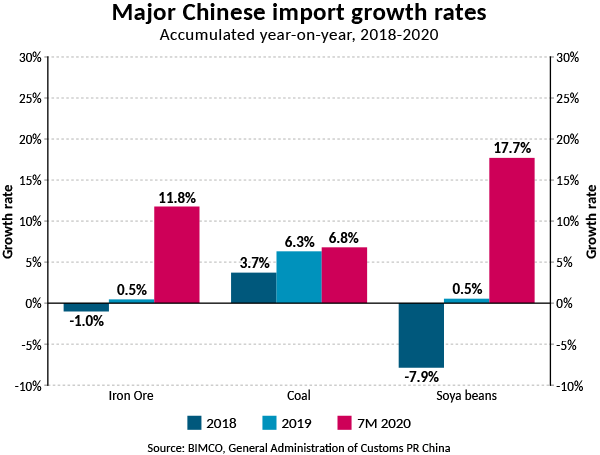

In particular, Chinese iron ore imports have been strong and are up 11.8% in the first seven months of this year compared with last – an additional 348 Capesize loads (200,000 tonnes). At 112.6 million tonnes, imports in July were at a record high, bringing total imports in the first seven months of the year to 659.6 million tonnes.

Higher steel production levels are, in part, behind the higher iron ore imports. Stimulus measures from the Chinese government are prompting local governments to invest in infrastructure projects, encouraging steel production. After monthly declines in March and April, Chinese crude steel production has recovered and, after seven months, is up by 2.8%.

The rise in steel production in China comes at the same time as production is falling in the rest of the world (-16.5% year-on-year), as the recovery elsewhere lags behind. This development means that, in Q2, China accounted for a record high 62% of global steel output, up from 54% in 2019. EU steel production was down 24.4% in July from last year, drops largely driven by the collapse of many manufacturing sectors, in particular Germany’s car production.

The high iron ore imports come after a few years in which Chinese steel production (+8.3% in 2019 and +6.6% in 2018) has grown faster than its iron ore imports, as it has moved towards using more electric arc furnaces and scrap steel, rather than blast furnaces. Looking at the whole picture, the higher steel production and infrastructure investment cannot fully explain the rise in iron ore imports and much of it will make its way into stockpiles.

In contrast to Chinese iron ore imports, which have grown throughout the year, coal imports did not grow in Q2. Since April, monthly coal imports have been below the corresponding month in 2019. In July, imports were 6.8 million tonnes lower this year than last. The strong start to the year – boosted by cargoes arriving at the end of 2019 but only clearing customs in January and February because of local restrictions – means that, despite the fall in Q2, accumulated year-on-year growth is still up by 6.8% in the first seven months of the year.

Lower electricity demand as a result of the pandemic has caused U.S. coal production to fall. In the week of 29 August, U.S. coal production stood at 11.1 million metric tons, 26.7% lower than the same week last year. Year to date, U.S. coal production is down 26.9% from last year. The Energy Information Administration (EIA) expects that, over the full year, U.S. exports of metallurgical coal will fall by 32.3%, to 37.3 million tonnes, and thermal coal exports will drop by 30.2%, to 26.3 million tonnes. In total, the drop in U.S. coal exports would mean a loss of 319 Capesize loads (200,000 tonnes).

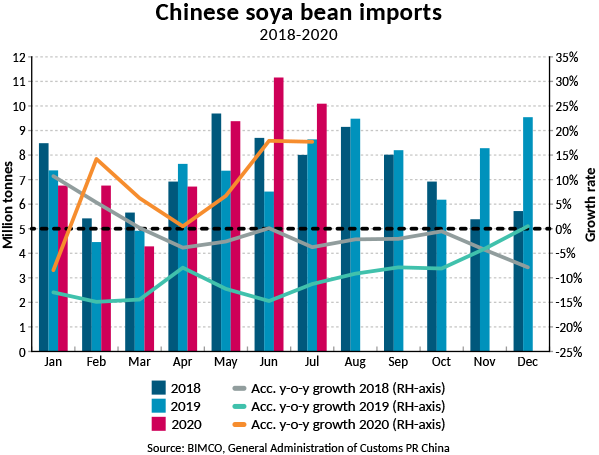

Iron ore and coal trades provide demand mainly for Capesize ships, while the smaller ships – in particular, Panamaxes and Supramaxes – have experienced higher demand because of strong agricultural exports. Brazilian soya bean exports have been at a record high this year. So far, they are up 36.3%, at 69.8 million tonnes. Compared with last year, this is an increase of 248 Panamax loads (75,000 tonnes), three-quarters of which sailed across the world to China.

These strong agricultural exports have helped drive Panamax earnings up to $15,815 per day on 19 August, and Supramax earnings to $10,494 per day.

Fleet news

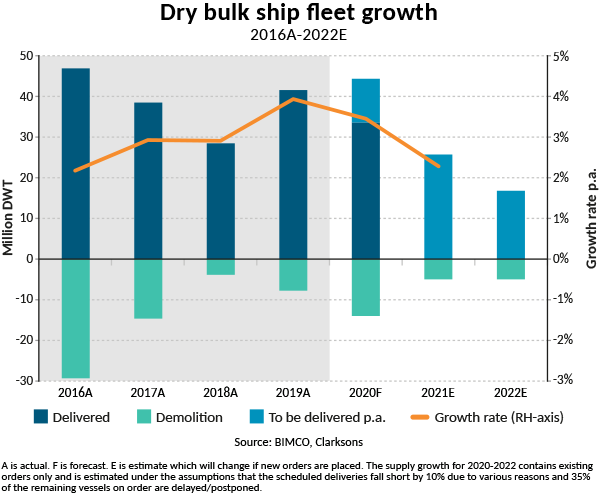

The dry bulk fleet has seen both deliveries and demolitions rise over the course of the pandemic, while contracting has fallen steeply. So far this year, the dry bulk fleet has grown by 2.8% and breached 900 million dead weight tonnes (DWT) for the first time. Currently at 903.3 million DWT, BIMCO expects full-year growth to reach 3.5%. On the other hand, the orderbook has fallen to 63.4 million DWT, its lowest level since April 2004.

Deliveries have risen by 7.8 million DWT from this time last year, with 33.9 million DWT of new capacity arriving on the sea in the year to date. Of this, just less than half of the tonnage comes from the 70 new Capesize ships that have been delivered (15.5 million DWT). Given that an average Capesize ship carries six loads a year, these new ships can carry 495 loads (200,000 tonnes) a year. The 111 new Panamax ships will be able to carry an additional 893 loads (75,000 tonnes), as these average seven loads a year.

A sharp increase in fleet growth, as a result of these deliveries, has been somewhat offset by an increase in demolitions, but the fleet continues its growth, because even an 69.4% increase in demolitions, compared with last year, only amounts to 8.7 million DWT being demolished.

The pandemic and the poorer outlook have caused a 59.1% fall in contracting activity, as owners have not wanted to invest during a recession plagued by uncertainty. Only 108 new dry bulk ships have been ordered in 2020, totaling 7.5 million DWT. Of these, 10 are Capesize ships (210,000 DWT) all of which have been ordered by Chinese leasing interests. The most popular ship size has proven to be Handymaxes, of which 62 have been ordered, totaling 3.5 million DWT, the majority of which have a capacity of between 60,000 and 65,000 DWT.

Outlook

With the start of September comes the start of the U.S. soya bean export season, when the U.S. replaces Brazil as the main exporter for the rest of the year. Outstanding sales of U.S. soya beans for this marketing year – representing what has been ordered, but not yet shipped – total 24.2 million tonnes, significantly up from the start of last season (9 million tonnes). China accounts for 56% of total outstanding sales for this season.

While it is yet to be seen whether these soya beans will actually reach Chinese shores, even these higher sales are far below what is needed under the Phase One agreement between the two countries. China, however, has already stockpiled plenty of soya beans after record-high imports from Brazil, with total imports up 17.7% from last year (55.1 million tonnes). The continued impact of African swine fever has also reduced Chinese demand. As such, BIMCO does not expect strong U.S. soya bean exports this season, but would be pleasantly surprised should they come about as goodwill purchases ahead of, or immediately after, the November election in the U.S.

Tensions have also been rising between China and other countries, including Australia, China’s largest supplier of iron ore and other dry bulk imports. The tensions, ostensibly over the handling of the virus, run deeper, with Australia ready to step up to the giant, despite its dependency. So far, Chinese coal imports from Australia have seen delays, though iron ore has been untouched. In fact, iron ore exports to China have been very strong: Port Hedland exported a record 46.2 million tonnes of iron ore to China in June. However, the stockpiling in China may suggest it is preparing for a further escalation of tensions.

Whatever happens between Australia and China, higher stockpiles in China of iron ore and soya beans lower the prospects for the dry bulk industry. At some point, freight rates will feel the pain of the demand that has been brought forward.

Given the importance of China to the dry bulk market, the recovery in industrial production and massive imports there have, so far, been enough to support the market. However, the rest of the world needs to join the recovery wave if this is to be sustained, to stimulate demand in other areas of the world, as well as to ensure that China’s recovery doesn’t falter because of the lower international activity. With COVID-19 cases still rising, a global recovery seems some way off.

Even with higher demolitions, the fleet will grow by 3.5% this year while, on the other side, demand falls, and faces a slow return to pre-pandemic levels. The dry bulk market – already struggling before the pandemic – is now looking ahead to even more challenging times, and the industry most certainly does not need to see the currently low orderbook grow.