Harold Eugene Doc Edgerton

Harold Eugene ‘Doc’ Edgerton was born in Fremont, Nebraska, on April 6, 1903. He was one of three children born to Frank and Mary Edgerton, and from an early age Edgerton like to see what made things tick, spending hours taking things apart and putting them back together. He first became interested in photography through his uncle who was a studio photographer, and his uncle would spend time with the young Edgerton showing him the ins and outs of photography including developing and printing the pictures they took.

Edgerton went on to receive a degree in Electrical Engineering in 1925, and took a one-year research position at General Electric in New York, a position that would prove pivotal in his development of the strobe.

Following this Edgerton went on to work on his graduate degree at Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT). At MIT he began to study the problems of synchronous motors, in which the speed of the motor is the same as the frequency of the electric current running it. He was most interested in what happened when a sudden change, like the surge caused by lightning striking the power lines reached the motor. Parts of the motor spun so fast that his eye could not see what was happening.

Edgerton noticed that a tube he was using to send power surges to the motor flashed brightly as the power peaked. When the flash of the light synchronized with the motor’s turning parts, it made them look like they were standing still, and they could then be analyzed.

Edgerton received his graduate degree from MIT in 1927 and was given an instructors position the following year. He earned his doctorate degree four years later with his dissertation that included a high-speed motion picture of a motor in motion made with a mercury-arc sub strobe.

Edgerton continued to improve strobes and their use in freezing objects in motion so they could be captured on camera. He also continued to make improvements in stroboscopic technologies. An early use of the stroboscope was in a lawsuit between Procter & Gamble and Lever Brothers on the methods they were using when making soap powder. Edgerton’s stroboscopic method proved Lever Brothers methods did in fact differ from Procter & Gamble, and the lawsuit was dropped.

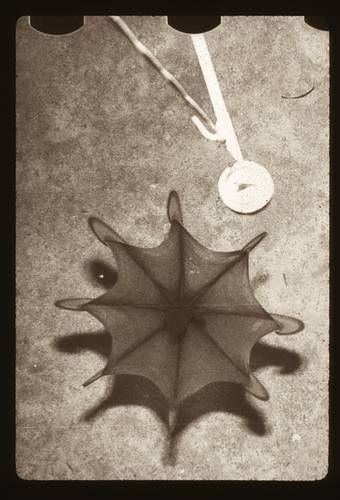

Edgerton then became interested in the particular challenges faced when dealing in the underwater environment. He had designed tools that could withstand pressure while being protected by the saltwater environment. He began to develop underwater cameras and lights as well as imaging recording instruments that were at the cutting edge of oceanographic research for that time. His instruments used light and sound and were used in many application of ocean research. Edgerton’s area of expertise involved the precise control of high-energy short pulses. These were used in stroboscopes, modular switches for atom bombs, and high speed flashes. These were then applied to the problems faced by underwater acoustic waves. By improving and shortening the sound pulse length he was able to improve resolution. His acoustic based tools included side scan sonar, sub bottom profilers and pingers. Because the cost of operating in the ocean environment was high, expeditions often had overlapping scientific missions. He worked with a number of explorers including Jacques-Yves Cousteau who approached Edgerton to collaborate on acquiring deep-water images.

In the mid-thirties Edgerton was approached by an expert in bioluminescence to photograph deep-sea bioluminescent fish.

This led to his first successful development of an underwater camera for oceanographic research through collaboration with the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institute (WHOI). His systems included hand-held, deep-sea, stereo, elapsed time and silhouette. Lighting instruments developed by Edgerton included strobes for various submarine vehicles, and strobes for underwater cameras.

Known to everyone as “Doc” Edgerton, he is considered a pioneer in a number of areas including underwater photography and marine technology.

MTR recently talked with Dr. Kim Vandiver who is the Director of the Edgerton Center at MIT. Dr. Vandiver worked with Edgerton as a graduate student at MIT in the early 1970s.

What are some of the interesting earlier projects you were able to work on with Doc Edgerton?

Well I was his TA in 1972 -73 and that was in the midst of his preparations for going out and looking for the Monitor.

He was in and out of the lab building cameras and loosing cameras. On the first dive down they lost a camera that got tangled on the wreck. They lost it and had to go back and retrieve it later.

What was it like working with Doc?

When Doc died in 1990 the family and Edgerton foundation put together a little committee and came to MIT interviewing people. They asked them what was special about Doc and what should we do that would be an appropriate legacy to him. Everybody was talking about the photographs because they were famous, but I took a little different point of view. What made Doc so loved by students and faculty and everybody at MIT was that he was an extremely generous person. If a student came in and said they had always wanted to do something or learn how to build something Doc would always say, ‘Well, there is a lab bench and a soldering iron, it only takes a few micro-seconds, what are you waiting for?’ He would give space, he would give materials, and he would give advice.

He sounds like he was an incredible mentor.

He was. I remember one day when I was his TA and we had something called the freshman seminar, when students would show up once a week and we would show them films. One thing he was famous for was his post cards. Doc never carried business cards. If you ever met Doc, sitting next to him on a seat in an airplane you would not leave without one of his post cards. He would strike up a conversation with anyone and hand them a post card. On the back of the post card he would have printed many of his iconic shots, and they had his name and address on the back of them and he would just hand them out like popcorn. If you ask people one thing they can remember about Edgerton even if they only met him once it would be the postcards. That is the way he was, you could be standing outside of his office looking at his images and he would walk out and strike up a conversation and give you a postcard.

It also sounds like his students admired him a great deal.

They did. One time one of the freshman showed up at the door and Doc and I were standing at the door as the students were filing in. There was this one freshman that was looking sort of sheepish and he asked Doc “would it be OK if my girlfriend came to class?” Doc gave the young lady this really stern look and said “You can’t get into my class without a pass.” She about looked like she was going to die and Doc reaches into his pocket and pulls out a postcard and hands it to her and says, “here’s a pass.” He was a character but a really generous character. People loved him for his sense of humor but also they deeply appreciated all he did for people.

He was not only a pioneer in his work but sounds also like a great motivator.

He was. My first year as his TA he told me he did not want me to simply assist but to actually work on a cool project while I was there. So I worked on a photography technique called slieren and took about five months to perfect it. I then walked into his office and he said I think you have got it.

What is slieren photography?

It is used in super sonic wind tunnels to see shock waves on aircraft. You can take pictures of bullets and see heat waves from a candle. I had my first professional publication while working with Doc. He was a remarkable man.

(As published in the January/February 2013 edition of Marine Technologies - www.seadiscovery.com)