WHOI Scans Ocean for Fukushima Radiation

With concern among the public over the plume of radioactive ocean water from Fukushima arriving on the West Coast of North America and no U.S. government or international plan to monitor it, a new project from Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI) is filling a timely information gap.

Just two weeks after launching the crowd sourcing campaign and citizen science website, “How Radioactive Is Our Ocean,” WHOI marine chemist Ken Buesseler’s project has received more than 70 individual donations from the concerned public. New data on seawater radiation levels will be posted on the website today.

“We’ve received a lot of interest from the public so far, which has been great. Right now we’re gathering important baseline data, but we need continual support in order to monitor the plume over the long-term,” said Buesseler, who conducted the first major sampling off shore of the Fukushima plant in June 2011 and again in 2013.

Through “How Radioactive Is Our Ocean,” the public can support the monitoring of radiation in the ocean with tax-deductible donations to fund the analysis of collected seawater samples or by proposing new locations and funding the samples and analysis of those sites at Buesseler’s lab in Woods Hole, Mass.

The project aims to inform and include the public in the process of gathering information about radiation levels in the ocean. The website has garnered more than 18,000 visits to-date.

Although Buesseler does not expect levels to be dangerously high in the ocean or in seafood as the plume spreads 5,000 miles across the Pacific, he believes this is an evolving situation that demands careful, consistent monitoring to make sure predictions are true.

One community activist in Point Reyes, Calif., has already raised enough funds to sample the seawater in his coastal community at four intervals throughout this year.

“We need to know the actual levels of radiation coming at us,” Bing Gong says about what motivated him to get involved. “There’s so much disinformation out there. We really need actual data.”

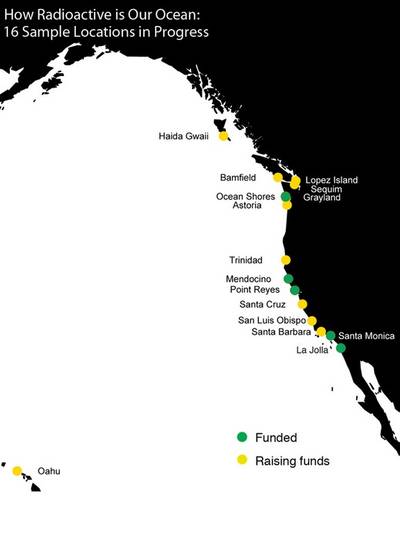

In addition to the Point Reyes site, thus far, funding has been secured for bi-monthly sampling at the Scripps Pier in La Jolla, Calif., and goals have been met for at least single samples at Ocean Shores, WA, Santa Monica, Calif., and Mendocino, Calif.

Dr. Roger Gilbert, a radiation oncologist in Mendocino, Calif. raised funds to support analysis of his coastal community’s seawater.

“My motivation was concern over fear-mongering on the Internet about allegedly high levels of Fukushima radiation in the coastal waters of California. I am a radiation oncologist, more familiar than most with radioactivity, and it seemed highly likely that the vast dilution of radioisotopes from Fukushima by the Pacific Ocean would result in a barely (if at all) measurable rise in counts,” he says.

Community activist Bing Gong raised $2,200 from friends and neighbors and plans to continue to raise enough funds to sample the seawater off Point Reyes over the next three years.

“What we really need is support to sample the same sites multiple times over the next couple of years, like the support coming from the community in Point Reyes, where we will be able to fully monitor the plume’s arrival and movement over time,” Buesseler says.

The plume of radiation from the Fukushima Dai-ichi nuclear power plant is forecasted to be detectable at the Pacific coast in April 2014, according to a scientific model developed by Vincent Rossi, a post-doctoral research associate at the Institute for Cross-Disciplinary Physics and Complex Systems in Spain.

Rossi’s model projects that traces of Fukushima’s radiation will reach Alaska and coastal Canada first because of the trajectory of the powerful Kuroshio Current that flows from Japan across the Pacific. The plume will continue to circulate down the coast of North America and back towards Hawaii.

Fukushima contamination can be “fingerprinted” from precise measurements of the relative amounts of two cesium isotopes: The long lived cesium-137 isotope with a 30-year half life that has been in the ocean from 1960s weapons testing, and cesium-134, with a 2-year half life that can only be a result of the more recent 2011 Fukushima accident. Today new data will be posted on the website from four funded sample sites: La Jolla, Calif., Point Reyes, Calif., Grayland, WA, and Sequim Bay, WA.

No traces of Fukushima’s cesium-134 have been detected in Buesseler’s analyses yet. And, the level of cesium-137 is what's expected from the 1960s sources (1.5 Bequerels per cubic meter).

“The reason why we see such low levels of radiation in these samples is because the plume is not here yet. But it’s coming. And we’ll actually be able to see its arrival,” Buesseler says. “That baseline data is critical.”

Having samples from before the plume reaches the coast is important for building a complete data set that measures changing radiation levels over time and improving scientists’ ability to model plume behavior.

“We expect over the rest of 2014, levels will become detectable starting first along the northern coastline. But the complex behavior of coastal currents will likely result in varying intensities and changes that cannot be predicted from models alone,” Buesseler says.

The project currently has sponsors interested in collecting samples from 16 unique locations from San Diego to British Columbia and one in Oahu, Hawaii. However, none have been proposed yet from Alaska, where the plume is predicted to be detected first.

“Optimally, we’d like to be able to sample and analyze about 20 sites from Alaska to San Diego at regular intervals every few months. We even have had interest from the public as far away as Japan, New Zealand, Guam, and one sailing vessel traveling from Hawaii to Japan this summer, but the West Coast time series is our highest priority,” says Buesseler.

About the project

Nearly three years after the tsunami that resulted in the Fukushima Dai-ichi nuclear power plant accident, questions remain about how much radioactive material has been released and how widely and quickly it is dispersing in the Pacific Ocean. Marine chemist Ken Buesseler at the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI) has been gathering samples -- some from as close as half a mile from the damaged reactors -- and has been analyzing this seawater for Fukushima contaminants since 2011.

No U.S. government or international agency is monitoring the spread of low levels of radiation from Fukushima along the West Coast of North America and around the Hawaiian Islands. The Center for Marine and Environmental Radioactivity (CMER) at WHOI, a private non-profit marine research and education organization, launched this project to involve the public in gathering seawater samples and raising funds for analyses that will provide the latest information about radiation levels in the ocean. The data is being posted on the website, www.ourradioactiveocean.org. Support for CMER’s on-going efforts to train the next generation of radio-marine chemists can be given by donating to its capacity building campaign.

whoi.edu