Are Offshore Ports the Future?

The benefits of offshore ports in the U.S. & Africa

In many parts of the world, offshore ports are a good solution for meeting the requirements of the rapid changes in the international container and bulk shipping industry. Bigger ships, changing routes and destinations require larger and deeper ports, which port owners and operators can be confident will be capable of handling ever-increasing sizes of vessels for many years to come.

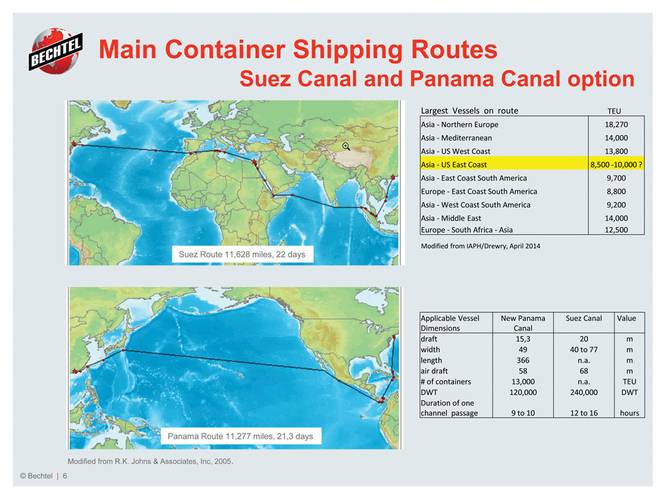

Changing Shipping Routes

One of the major challenges in the current container shipping industry is to bundle and organize capacity in the most economical way. In terms of vessel size, Maersk is leading with its Triple E vessels, but the capacity of these new, larger ships needs to be combined with other main carriers in order for it to be effective. Various alliances have been formed, and new ones are being developed. As part of this process, capacity is being shifted to routes which haven’t changed for many years, for example in West Africa. Due to the so-called cascading down process, ships which were never originally intended for use in West Africa will now soon be there. Ports like Abidjan are already anticipating these changes and looking at possible solutions. Others are talking about it but haven’t really started to tackle the issue yet. However, many of the traditional ports lack the physical possibilities (in terms of size, depth, finance, etc.) to make the changes required to enable them to cater for larger vessels and increased capacity. As a consequence, offshore hubs along parts of the West and East African coasts are a solution: in the Guinea–Liberia region for the export of minerals; in the Cameroon–Gabon region for containers; and in Mozambique for bulk. The benefits are massive. We’ve predicted that the savings in investment and operational costs could add up to between 40 to 50 percent.

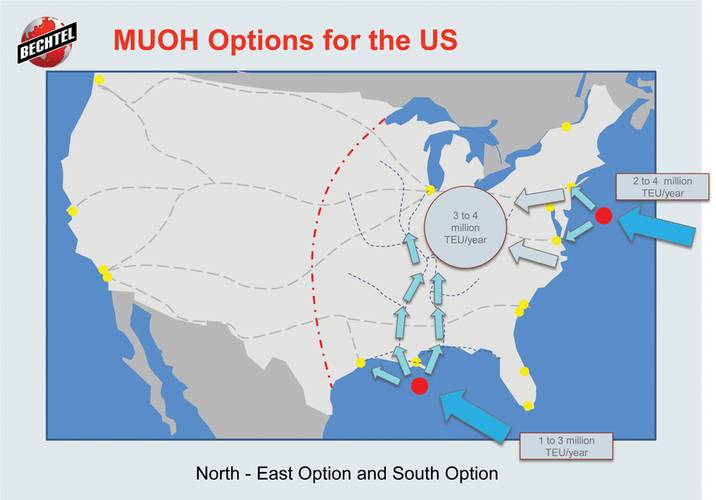

Similar developments can be seen on the East Coast of the U.S. Due to the same cascading effect and the fact that the biggest container vessels can sail direct via the Suez Canal straight to the U.S. East Coast, an option that is rapidly developing as an alternative for the New Panama Canal. The route via Suez has a greater degree of freedom in terms of ship sizes, especially when the planned increase in two-lane capacity is ready. The big question now is if and how quickly the U.S. East Coast ports can adjust to this development. New cranes have just been ordered and installed for the New Panamax vessel sizes. Some ports have dredged their channels and quays and widened their basins at substantial cost. Others aren’t yet ready to do this, which might be an advantage. Investing in an offshore port could be the best solution by providing a hub for a whole region with fewer limitations for long term development than is often the case in existing ports without limitations in free height (draft), which is an issue in New Jersey for instance, or for various environmental reasons.

Are Offshore Ports a Solution?

Some coasts are just not suitable for deep water ports due to their extended shallow foreshore. For a required water depth of say 20 m, a deep water port might need to be 15 km or more away from the shoreline. This is a situation found along large parts of the African coast, particularly in West and East Africa. So instead of bringing the ship to the port and dredging long and deep channels and port basins on the coastline, one solution could be to bring the port to the ship at the required water depth with an offshore port providing various handling facilities for bulk and/or terminals for containers. Barging the cargo to and from the offshore facility and terminals to nearby coastal or river ports, and using existing corridors and facilities can thus save on capital construction and operational costs. It can also reduce the environmental impact and minimize the ecological footprint. By concentrating present and future development in one spot, an offshore port could work very well not just in Africa but also in the U.S. Currently, up to 70 percent of all West Coast containers move east by rail and road. If only 20 percent of these containers would shift from overland transport to all-water direct import via the Suez Canal to an East Coast offshore port, this would save:

• 20 to 30 percent on direct freight costs from the Far East to the U.S. East coast due to the all-water economy of larger scale shipping

• 30 to 40 percent (or even more) on direct freight costs due to 40 to 50 percent shorter overland transport distance in the U.S. itself

• 20 to 30 percent in emissions on the all-water-route (lower fuel consumption, more efficient engines) plus a 40 to 50 percent reduction in overland transport emissions.

The estimated overall cost reduction for an East Coast multi-user offshore hub compared to improving existing ports and relying on overland transport to be between 30 to 40 percent for both investment and operations. And lower freight costs could also mean lower consumer prices and therefore be better for the overall economy. Instead of ships first going via Caribbean hubs, having an offshore port hub in the United States would mean that without extra handling, the industry can keep money and jobs in the U.S.

For the mining industry, using an offshore hub would provide overall better performance and therefore easier overall feasibility of the whole development, which means earlier viability of the development of the whole prospect. Mining projects that weren’t feasible in the traditional setting with a rail link and one or more coastal ports can become viable when choosing an offshore hub. Even more so, when in combination with (inland) barging or coastal shipping.

The Concept

In the offshore port model, no dredging is required as the facility is placed in water of sufficient depth, say 20 to 22 meters. In order to avoid or reduce the need for expensive breakwaters, technologies such as dynamically controlled mooring and proactive fender systems will be used to guarantee safe operations and a sufficient wide operating window for handling the cargo.

For bulk, the degrees of freedom are usually much larger than for containers, which is why these dynamic systems are being used on an increasing number of container terminals all over the world, especially in existing ports with heavy swell issues.

For containers, the offshore hub would consist of a smart terminal arrangement of say two or three berths for the main carriers and four or five for barges to nearby ports and coastal shipping. The facilities can be extended in almost any combination with dry bulk, wet bulk and containers, depending on zoning and safety requirements.

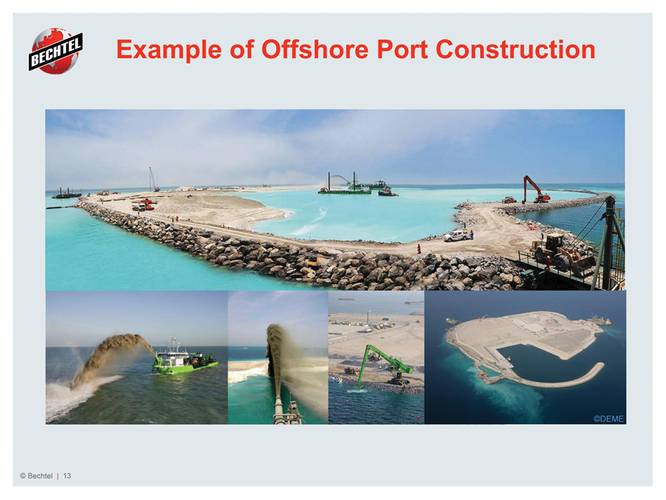

This concept is not entirely new. Bechtel has already built the deep water Khalifa Port and Khalifa Industrial Zone in Abu Dhabi, one of the world’s largest combined port and industrial zone developments. However, Khalifa Port is connected to the mainland by a causeway and bridge and the offshore hub proposal is essentially an island. There are similarities in terms of port and terminal operations, as well as scale. The offshore hub would be able to handle up to 4 million TEU per year.

Conclusion

The offshore hub represents a viable solution to the future needs of ports, which need to adapt to the ever-increasing sizes of vessels, particularly in the U.S. and Africa. Offering the opportunity to save costs, minimize environmental impact and increase capacity, this concept could provide the answer where traditional ports cannot. Its prospects look promising. In Africa, the multi-user offshore port concept provides a strategic solution by maximizing the benefits of infrastructure corridors. While in the U.S., Bechtel is currently in discussions with various government agencies about the development of an offshore port on the East Coast.

The Author

Marco Pluijm is responsible for the Bechtel’s Port and Marine sector, which includes business and project development, worldwide, technology development, as well as innovation in the maritime sector. He has more than 35 years’ experience in planning and building ports across the globe. As part of the innovation cluster, he is currently leading a joint-industry project (JIP) into the safer mooring of large cargo ships in open water, transhipment, along the coast of West Africa. And recently led the highly-acclaimed ROPES JIP research project for the assessment of the quantitative effects of passing ships on moored ships, which resulted in new international guidelines for the design of safer ports. Mr. Pluijm previously worked for a port authority, a dredging company, an international port consultancy and the Ministry of Transport in the Netherlands. He has an MSc Civil Engineering in port planning and design from Delft University of Technology, the Netherlands.

(As published in the December 2014 edition of Maritime Reporter & Engineering News - http://magazines.marinelink.com/Magazines/MaritimeReporter)