Was the closing of the Houston Ship Channel for over three days in March 2015 due to the use of Ultra Low Sulphur Fuel Oil (ULSFO)? After reviewing the testimony, and evidentiary material presented by the National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) regarding the 2015 Conti Peridot’s collision with the Carla Maersk, it is the authors' opinion the report fails to address significant contributing factors. The NTSB has overlooked a serious threat to vessel operations throughout the world. In its oversight, NTSB’s findings set the foundation for future collision, allisons and groundings by not acknowledging the threat these conditions pose and recommending remedies for them.

While NTSB’s report recommends that the local harbor safety committee study ways to help avoid accidents during the rapid onset of fog and other foul weather, it is our position that the root cause of the crash was likely the combination of low sulfur fuel complications and the ship’s poor handling characteristics which caused the bulk carrier to veer and slow just when it needed increased RPMs to meet the Carla Maersk.

NTSB noted in a Board meeting on June 7, 2016 that “Navigation equipment, vessel propulsion and steering systems, alcohol and other drug use, fatigue, medical conditions and medication use, and distraction from personal use of electronic devices were not factors in this accident.”

NTSB’s finding that vessel propulsion did not contribute to the incident between the Conti Peridot and the Carla Maersk raises particular alarm. The requirement to use ULSFO with sulphur content below 0.1 percent went into effect on January 1, 2015. Terminology for this type of fuel is confusing. The USCG in its Marine Safety Alert 13-15 (https://www.uscg.mil/hq/cg5/cg545/alerts/1315.pdf) uses the term ULSFO but this is a bit of a misnomer. A residual fuel oil is defined as a product with a viscosity over 12 centistokes (CST) and gas oil is defined as a product with a viscosity under 12 CST. Most of the ultra low sulfur fuel used by ships today, transiting within ECAs are low sulphur marine gas oils (LSMGO).

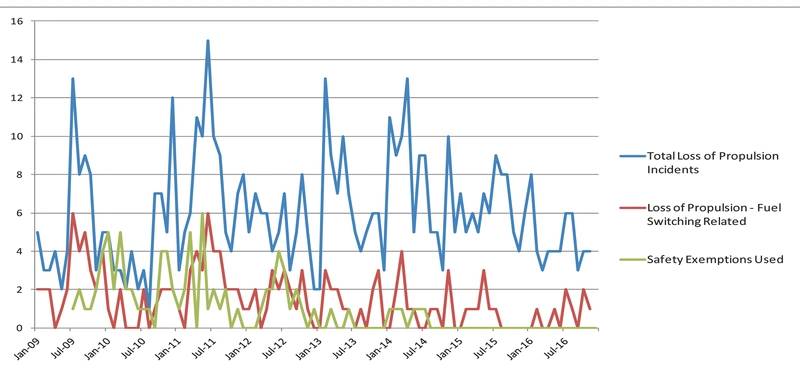

Since this start date harbor pilots are not only seeing loss of propulsion (LOP) issues, but also the inability of some vessels to deliver critical increases of RPM in a timely manner (less than 30 seconds) to aid in steerage (known as a “kick” in harbor pilot vernacular).

According to Henry H. Hooyer in Behavior and Handling of Ships:

“When the ship is under rudder at the moment of increase in engine revs, we have an increased thrust on the rudder as well as a momentarily increased leverage of the rudder while the ship proceeds at a comparatively low speed through the water. The improved steering will last until the resistance forward corresponds again with the engine revs.” (Chapter 2, p 30, 2004).

In layperson terms, the combination of forces creates greater maneuvering capability without creating greater speed. ULSFO in some instances may not support this maneuverability.

A timely “kick” on the engine in a narrow channel is a critical tool in a pilot’s toolbox, but the characteristics of ULSFO may take it away. This is adding more risk to navigation in these areas.

The pilot on the Conti Peridot went to half ahead prior to meeting two ships for several reasons. Visibility was bad, the ship was handling poorly, and there was an inbound tow ahead that he did not want to overtake while meeting the second outbound ship. He felt confident that with a ‘kick’ in his back pocket the next few meetings would go smoothly. Pilots are also finding some vessels are having problems at the low end, in that they cannot stay on what is called a “dead slow bell” when anchoring or berthing without having a loss of propulsion.

Engine manufacturers design ship engines to run on residual fuel as the primary fuel source since it is both the prevalent fuel in the market and the cheapest but it requires heating (150°C) to enhance flow characteristics. The engines may also run on ULSFO (50°C ), but operational parameters are markedly different.

Slow speed compression ignition engines use the fuel oil in the fuel systems to lubricate internal parts of the system such as fuel pumps and injectors. Residual fuel oil has plenty of sulfur, which actually has lubricating properties necessary for this internal lubrication. Sulfur contributes a micro corrosion on close tolerance metal parts that affords lubricating molecules adhesion. ULSFO is designed to reduce emission pollution, specifically for sulfur dioxide. It does not contain sufficient sulfur to provide the internal adhesion affording the lubrication that fuel systems need, and sometimes requires a lubricity additive in the fuel. Manufacturers also recommend close tolerance parts be changed out when wear is at 10 percent of new specification. Not adhering to this recommendation is more common than it should be. This accentuates “O” ring leakage in the engine room creating a fire/safety hazard. Review of the service letters and technical papers from the “MAN Marine Engine & Systems” reveals a recurring theme. The following are critical for ship engine operations

- Correct viscosity and fuel pump pressure

- Correct temperature

- Proper cylinder lubrication (This is referring to slow speed main engine cylinder lubrication via injected cylinder lube oil and not fuel pump and injector lubrication via the fuel consumed)

- Fuel specification

If any of the above criteria are not met, then the use of ULSFO may cause performance issues.

Introduction of International Maritime Organization (IMO) – Emission Control Areas (ECAs) only spoke of Sulfur content and its verification. It does not focus on engine modification/suitability and leaves that to the ship owner. ECA requirements focus primarily on controlling emissions by ensuring sulfur in the fuel is maintained at certain levels. IMO set certain standards to measure and verify the levels of sulfur in the fuel provided to the vessel. Beyond this requirement, the fuel specs are very relaxed.

The ship crews use what they think are workable procedures – with no verification if they followed the manufacturer’s circulars for conversion to ULSFO. Manufacturers advise attention be increased to wear on components.

Though engine manufacturers have been issuing guidelines for use of ULSFO, there is no enforcement or verification mechanism in place. Vessels owned and/or operated by responsible management teams are having fewer of these failures, but they can still occur so diligence is required. The key goal should be to educate ship owners, operators, and pilots with the information they need to safely and efficiently handle, treat, maintain and consume ULSFO onboard.

It is important for vessel personnel to understand the potential limitations on vessel maneuverability, especially those due to a change in fuel type. It is critical during the Master/Pilot Exchange that the Master share engine limitations due to ULSFO with the pilot. If the pilot is not getting this information, he should ask.

Having said this, it is important to point out that many ships are using the ULSFO in narrow waterways without any loss of RPMs or any additional time deltas between bells. This leads the authors to believe the problem is both maintenance and educational based.

The Houston Pilots passed on information collected regarding the incremental times on ships in the channel going from half ahead to full ahead. The times appear all over the place; however, the average is certainly well below the 3 minutes it took the Conti Peridot to increase RPMs. This information is conspicuously absent in the docket.

Early in the investigation, the Houston Pilots pointed out to the NTSB that the Conti Peridot exhibited poor handling characteristics. Did the NTSB in its evaluation consider this issue? It appears many of the vessel parameters that could have led to a review of why this vessel handled so poorly was never collected. An example of these parameters are:

- Rudder size compared to wetter surface area of the vessel

- Shape of the stern

- Ship’s block coefficient

- Engine Horsepower

- Time response between bells

The Houston Pilots also raised the issue of vessel trim with the NTSB. It was discussed that despite past efforts by the pilots, vessels continue to arrive even keel. Adding just 18” (46cm) of trim makes a huge difference in a ship’s handling ability. Would this have contributed to the incident?

Based upon review of the report and unaddressed critical issues, the authors make the following recommendations:

- Maritime industry regulators should consider requiring owner operators ensure that whatever fuel they use to comply with ECA requirements does not adversely affect vessel performance and any known operating characteristics be documented and made known to pilots during Master/Pilot exchange.

- Maritime industry regulators should engage stakeholders, including port, shipping, engineering interests, and classification organizations regarding the challenges of using ULSFO.

- Due to the immediate threat and danger posed by the use of ULSFO, maritime industry regulators should establish the necessary port entry requirements. To avoid the hazards effecting Ports within ECAs economically and environmentally due to vessel collisions, allisions or groundings.

The Authors

-Captain Jeff Cowan graduated from the California Maritime Academy, earning and sailing on his Master’s license.

-Claes Jakobssen sailed as a Chief Engineer (after attaining CE status at age 29) for three years for a Northern European shipping line, and is now working with shipping projects and shipping consulting.

-Mike Morris was a Houston pilot for 25 years, now retired former head pilot.