Washington Watch: Winds of Change in DC

For operators venturing into the offshore wind space, 2021 started off with a gust of changes and reports. From Jones Act clarifications and new enforcement authorities, to millions in port infrastructure funding, the new Congress and presidential administration will have plenty of tools available to shape the future of the industry’s development.

NDAA brings Jones Act changes

One of the most persistent questions that has hung over the development of the U.S. offshore wind industry has been whether the Jones Act will apply during both the construction and operational phases. The Jones Act, of course, requires the use of U.S.-flag coastwise-qualified vessels when transporting merchandise between two U.S. points. The Jones Act’s reach is extended offshore through the Outer Continental Shelf Lands Act (OCSLA), which was originally enacted by Congress to govern the exploration, development, and production of “minerals” on the U.S. Outer Continental Shelf (OCS). The National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2021 (NDAA), enacted by a Congressional veto override on January 1, 2021, however, amended OCSLA to clarify that the Jones Act (and all other U.S. laws) extend to installations on the OCS engaged in the exploration, development and production of non-mineral energy resources, such as wind.

The result is that U.S.-flag coastwise-qualified supply, crew transfer, and other support (and certain installation) vessels can look forward to steady work in the U.S. offshore wind market. There still will be opportunities for non-U.S.-flag vessels to participate, however, including in pipelay and cablelay operations, which U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) has long held to be outside of the Jones Act’s reach.

The NDAA further advanced Jones Act interests by revising the process by which Jones Act waivers can be issued at the request of the Secretary of Defense (SecDef). Following the issuance of numerous Jones Act waivers in 2011 during the Strategic Petroleum Reserve drawdown, the Jones Act waiver process was largely reformed to require the Maritime Administration (MARAD) to take certain affirmative actions when issuing a determination that no Jones Act-qualified vessels were available to perform the required service. In addition, CBP was generally required to make a report to Congress when issuing a Jones Act waiver. Notwithstanding these changes, however, SecDef was still permitted to request a waiver, which CBP would grant regardless of whether sufficient Jones Act vessels were available. The result is that, in recent years, this easier route through SecDef was used to waive the Jones Act following various national disasters.

The NDAA largely forecloses this option, by limiting SecDef waivers to those that are necessary in the interest of national defense to address “an immediate adverse effect on military operations.” Moreover, SecDef is required to make an immediate report to Congress, including a confirmation that there are insufficient Jones Act vessels available to meet the national defense need. In addition, the NDAA limits traditional (non-SecDef) Jones Act waivers to 10 days, with possible extensions not to exceed 45 days in total. In aggregate, the amendments appear to limit the Jones Act waiver statute to its original purpose, i.e., short-term limited waivers only when absolutely necessary to support a national defense need.

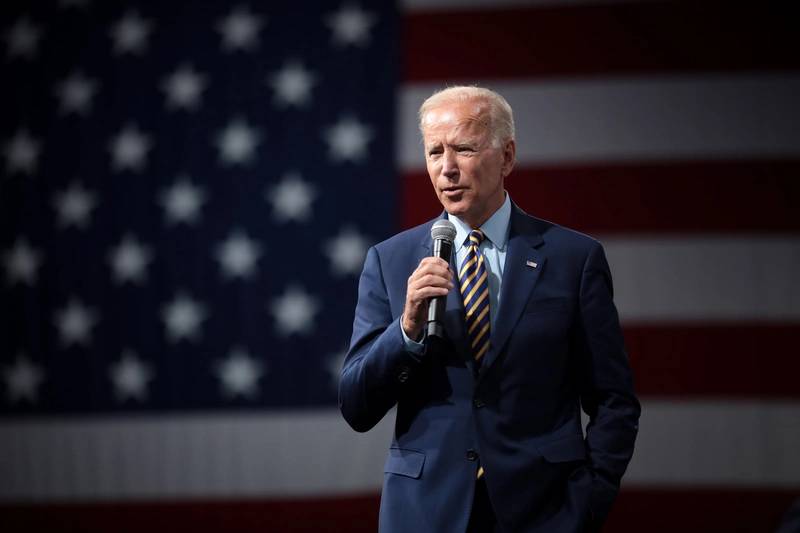

Joe Biden - Credit: Gage Skidmore CC BY-SA 2.0

Joe Biden - Credit: Gage Skidmore CC BY-SA 2.0

Change with the Biden administration

More changes may be on the way as the Government Accountability Office (GAO) released a report in December entitled “Offshore Wind Energy – Planned Projects May Lead to Construction of New Vessels in the U.S., but Industry Has Made Few Decisions amid Uncertainties”. The report highlighted the challenges in constructing new vessels for the U.S. offshore wind market, with stakeholders citing a hesitancy to invest due to uncertainty about the timing of federal project approval. These timing challenges were brought to a head in December when the Vineyard Wind project—which had been the forerunner in the federal permitting process—was officially withdrawn from federal review. The withdrawal may be a strategic move to delay further environmental reviews until the beginning of the Biden administration, which has promised to provide strong support for offshore wind development. During his campaign Biden touted wind energy as a cornerstone of his $2 trillion clean energy and infrastructure plan, pledging to install “tens of thousands of wind turbines.” Investors in the market no doubt will be focused on whether this pledge will mean an improvement to the current drawn-out environmental review process for pending offshore wind projects.

Once investors are ready to make the commitment in new vessels to support of the U.S. offshore wind market, MARAD hopes to offer attractive financing tools. As the GAO report notes, MARAD’s Federal Ship Financing Program (Title XI) could help fund the construction of such vessels. To that end, MARAD is making significant improvements to Title XI, to reduce the lengthy application timeline and difficult review process that has hampered the program in recent years. Indeed, in January, MARAD rolled out a new streamlined application review process, which may reduce the review timeline to as little as six months for well-qualified applicants. Given the long-term financing and historically low interest rates offered by the Title XI program, this should be an attractive option for investors in the U.S. offshore workboat market.

The GAO report also highlighted port infrastructure concerns as an impediment to new Jones Act compliant offshore wind vessels. As noted by various stakeholders, “U.S. ports close to planned offshore wind projects, particularly in New England, have limited ability to support offshore wind vessels because they lack the necessary space or infrastructure.” Stakeholders will undoubtedly watch with interest to see what actions the Biden administration will take in addressing these challenges as part of its comprehensive infrastructure development plans. Notably, the new administration will already have significant funding available as the Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2021, enacted on December 27, 2020, incorporated the Water Resources Development Act of 2020 to allow for the first-ever drawdowns from the $9.3 billion Harbor Maintenance Trust Fund balance. In addition, the omnibus spending bill provides $230 million in grant funds for MARAD’s Port Infrastructure Development Program and $1 billion in funding for the U.S. Department of Transportation’s BUILD grant program (which includes port infrastructure investments).

In aggregate, the coming months promise to be an exciting time for U.S. offshore wind stakeholders with a new Congress and presidential administration promising to support the industry’s development, much-needed Jones Act clarifications, and hundreds of millions of federal dollars available to support port infrastructure development.

(This article fist appeared in the February 2020 e-magazine edition of Marine News: The U.S. Offshore Wind Issue)