Shipyards Rising Competitive Stirrings

A mini order boom fueled by gas, “green-tech”, tankers and new rules is underway in shipbuilding. It won’t fill all yards, but changes like the July 2015 cap on sulfur emissions garner retrofit and rush orders. Even China’s Directive 55 obliges its mixed bag of yards to comply. Threatening to plug this trickle of business is the potential for backlash against rule makers, when Class is observed “engaging” some yards on designs while others must merely learn the new requirements. Environmental gains, too, might one day be lost, if rule makers are seen to be hindering and competing against the world’s shipyards rather than enabling them.

According to Yard Intel, deliveries of vessels of all types have outpaced orders so far in 2015, but the world order book has only declined seven percent to 6,579 vessels. The erosion slowed in May, and then continued in June, when 296 deliveries were made and 166 orders placed. June mostly saw the arrival of bulk vessels and the ordering of tankers, and that trend continues in the second-half of 2015.

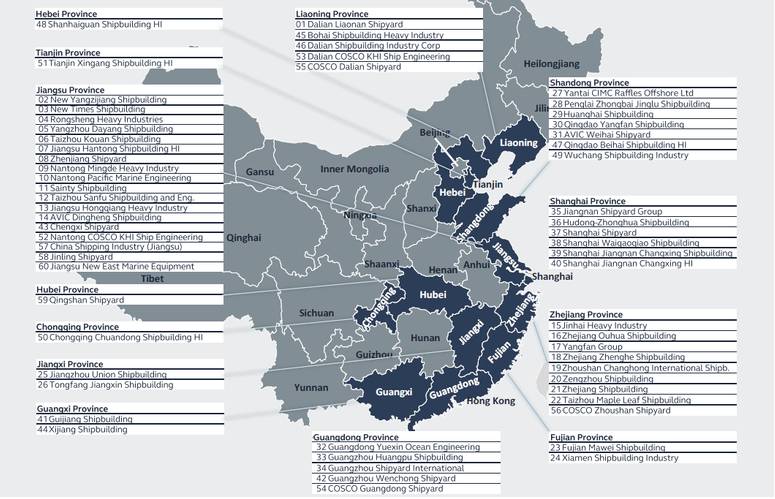

That’s the mini order-boom: 166 orders. It’s a lifeline, and the shipyards of some countries feel it more acutely than others. In China, 480 yards face strikes, upheaval, dwindling orders and a backlog of just 402 (62 offshore vessels, 64 tankers, 102 bulk carriers and 79 containerships).

Similarly, Indonesia, with 195 yards and deliveries over five years of 1,764 vessels has just 76 vessels still on its yard’s books.

Across the East China Sea in Japan, 126 yards churn out superior vessels, and 31 one of these fabrication centers — half of the gas-capable yards in the world — are advanced enough to handle gas technology in shipbuilding. It makes Japan an ally worth having for a Continent and a country keen to get the world’s oceangoing vessels onto natural gas. So, when a Nor-Shipping media event plays out with DNV GL announcing it has fostered a liquefied natural gas vessel design “in collaboration” with Oshima Shipbuilding Co., it raises some eyebrows, coming as it does during a deluge of Class announcements, including another joint design, and the coming promulgation in 2016 of new hull rules.

“We shouldn’t be doing design,” a Class expert from another society says, hinting that he believes the enabler role of Class is its stated and accepted mission.

The Class man in the presentation proclaims the Oshima LNG-fuelled Kamsarmax Bulk Carrier “a design that’s ready to order”. Although he had drawn “a simpler drawing” of the vessel, he said that Oshima was asked to come up with a robust design that didn’t use the hold. While the role reversal was noticed, a design now exists for cross-Atlantic voyages using LNG, heavy fuel oil and marine diesel.

Steadfast supply chain

For other yards coming to grips with sulfur in fuel, arranging retrofits for carbon dioxide scrubbers or ordering new-builds, it strictly business as usual: Class abidance.

“It’s impossible to deliver a new set of rules without also supplying the tools to implement them,” a Class man in another room tells a mixed audience of ship builders, lawyers and journalists.

New strictures for hull structures “regardless of type and other rules” and for the material requirements of metals used will be subject to “future proof” stress models. Meanwhile, the real “tools” of change — hybrid and dual-fuel engines, batteries, scrubbers, antifouling — will need global supplier assistance. Jotun, for one, is understood to have struck a deal to help Chinese yards apply emissions-cutting antifouling.

Sembcorp Marine, though re-branding and moving to new facilities, has anticipated the new clean-shipping rules. It has found a Norwegian partner to market modular LNG plant and has readied scrubber installation facilities. Though famous for its drillship designs, “It’ll probably be a multi-year period,” according to RBC’s Robert Pinkard, before any large-scale order activity resumes. Right now, drill ships are mostly under construction elsewhere in Asia and in Brazil.

Ship power heavyweight ABB is understood to be offering the tools of change in the form of gas-handling equipment and services, but “the yard will have to take the risk”, the cost of environmental enforcement. The power providers expects “more involvement at the yard from the charterer” and Class, although a process of training yard personnel and service contractors is understood to be underway. There’s a lot to learn, and most yards aren’t equipped to install a 1,200 kilogram 1 MW battery for hybrid power aboard a tug or coastal ferry, the hybrid market for now. The ship designs aren’t ready, and Class would need to move fast to clear extra hull supports.

Yard help

Alexandre Eykerman, Wartsila’s director of sales for ship power, is acutely aware of the peculiarities of the many class and International Maritime Organization rules, especially U.S.-applicable Tier III.

“We create sea areas with different requirements,” he says in mock exasperation. “In the U.S., you have to burn (heavy fuel oil) to be compliant,” he jests. While NOx and particulate emissions were Tier II requirements of 2011, Tier III has tightened up SOx.

“In ’95 it was dual-fuel. In 2015 it’s multi-fuel technology, heavy fuel oil and marine gas oil,” he says. Eventually it becomes known that Wartsila’s new No. 31 engine for offshore and oceangoing vessels is multi-fuel and low maintenance, precluding the need for separate catalytic reduction — understood to be high-maintenance process — that could find its way into many a clean-burning retrofit or new-build in need of emissions of less than 0.1 percent sulfur.

Despite these costly burdens for yards, ship owners and charterers, the maritime supply chain — including Class — looks ready to supply the tools of compliance. Able shipyards can expect extra business. Many, a source confides, don’t have the materials knowledge to produce the strong, lightweight (aluminum) hulls needed for, say, battery power.

To be sure, the yards’ abilities will be challenged by the mini order-boom of LNG and compliance-related work. Even among the very capable South Korean yards, just nine can carry out gas-related work, judging by data provided by Yard Intel. As the yards struggle to survive amid the changeover to cleaner technology, it might serve the cause of competition if they were not also competing with Class and its partner yards.

(As published in the August 2015 edition of Maritime Reporter & Engineering News - http://magazines.marinelink.com/Magazines/MaritimeReporter)