Aviator & Engineer: Lawrence Burst Sperry

A chip off the old block makes aeronautics his claim to fame

The U.S. Navy, and the aeronautic field in general, has benefited enormously from the genius of more than one Sperry. Lawrence Burst Sperry, the second son and third child of gyrocompass inventor Elmer A. Sperry was a pioneer in instrumental flight and famous inventor in his own right, launching the Lawrence Sperry Aircraft Co. at 26, and earning 23 patents before his untimely death at the age of 31 in 1923. Aviation promoter and Air Service General Billy Mitchell lauded him as one of the most brilliant minds and greatest developers in the world of aviation, while one newspaper called him “Uncle Sam’s youngest technical expert and aviator.”

It was no exaggeration.

Like his father before him, Sperry’s engineering brilliance more than made up for his lack of a college degree, and he too achieved acclaim in his early 20s as an innovator and inventor, primarily in aviation.

The youngest licensed pilot in the country, Lawrence first gained fame as the inventor of the autopilot, a small gyroscopic stabilizer for planes that controlled the three axes of flight — yaw, pitch and roll —to maintain course and altitude.

Most ships today still use a Sperry-type stabilizer to dampen rolling, along with some version of a Sperry autopilot linked to a Sperry gyrocompass.

He also invented the artificial horizon; a turn and bank indicator; the first amphibious flying boat; an airspeed indicator, a drift indicator, a significant improvement over the liquid-filled magnetic compass and a parachute pack – inventions that formed the basic instruments of all manner of planes and most of which remain in use today.

A font of ideas, Sperry also tackled night flying issues and built the first wheeled retractable landing gear in an amphibian. That got him a splash in the March 29, 1915 The Aerial Age Weekly.

But it was his performance at French air competition for plane safety in 1914 that turned him into an international star overnight and netted a $10,000 prize. With his parent looking on, the 22-year-old Sperry and his mechanic wowed the crowd, which included military observers, by walking out on the wings of the plane while it was aloft, to demonstrate his autopilot technology. Sperry, with his hands up in the air, offered a whole new take on “Look Ma, no hands!,” to an incredulous crowd.

By 1916, Lawrence was a commissioned junior lieutenant in the U.S. Navy and assigned as a flight instructor. A brief stint on active duty in 1918 was cut short by emergency surgery, enabling him to continue his focus on innovation. He was the first civilian to join the Navy Flying Corps Reserve in 1917.

Working with his father, Elmer A., the two developed one of the earliest drones – an unpiloted aircraft that could fly to a target guided, once again, by Sperry Sr.’s gyroscopic device. Despite some initial interest and funding from the Navy, however, uneven test results and trips back to the drawing board led the military to shelve the idea. It wasn’t until after their deaths, that interest in their idea was rekindled, driven by the eruption of WWII.

The Sperrys encountered similar luck with another project they first pitched to the Navy in 1916 - “air bombs,” or early guided torpedoes. “It’s easy to imagine a fleet of these weapons, loaded with deadly gas or explosives, launched against an objective without endangering one human life of the side so employing them,” explained Lawrence in papers published in 1926 after his death. Even though Lawrence’s company developed and patented a remote radio-controlled aerial Torpedo, and Elmer applied for a patent on a radio-controlled aerial torpedo in December, 1917, this work too was tabled by the Navy once the war ended. Lawrence’s patent foresaw the needs of modern cruise missiles, addressing internal guidance systems and post-launch guidance, among other issues,

After the war, in 1919, Sperry built two 48 ft. wingspan Land and Sea Triplane Amphibians for the U.S. Navy for coastal defense. With encouragement from Gen. Mitchell, he also designed a compact sport biplane for the Army Air Service in 1921.

The Sperry Messenger ran on a 28 hp, 3-cylinder radial engine, had a 20-ft. wingspan and could hit speeds of 95 miles per hour. His company also built the Verville-Sperry Racer for the Air Service featuring a retractable landing gear and a clean wing design. It won the 1924 Pulitzer Trophy Race.

Nicknamed “Gyro,” Sperry was a daredevil whose personally tested many of his instruments and technologies, included a public demonstration of his self-packing parachute. According the National Aviation Hall of Fame, Sperry jumped out of a plane, “falling 2,000 feet before pulling the rip cord. Unfortunately, winds carried him over downtown Dayton [Ohio] and he landed on top of its tallest building, as fire engines rushed to the scene. But when Lawrence calmly jumped from the building and floated safely to the ground, his father, an ardent prohibitionist, deadpanned, “I think we all need a drink!”

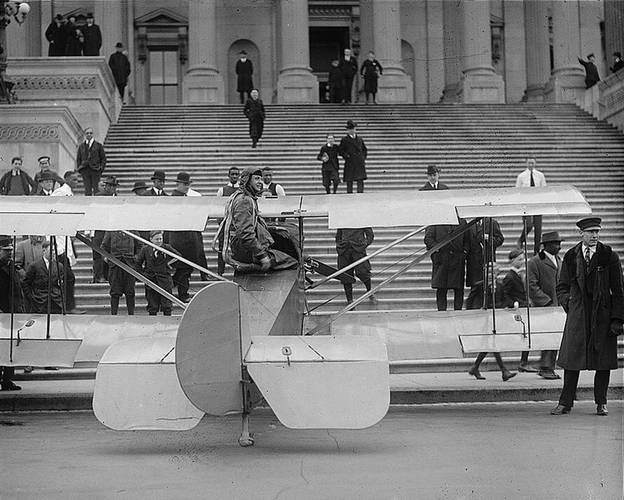

Other stunts included buzzing the Capitol to disrupt Congress and landing first on the Capitol steps, and then in front of the Lincoln Memorial before storming into the U.S. Treasury to collect money the government, which had been slow in paying his company for contracted work. Speaking of stunts, he is also considered by some the founding member of the “Mile High Club,” in 1916 after he and a married woman companion were fished out of the drink off Long Island buck naked after their plane crashed. Sperry famously claimed the impact blew their clothes off, inspiring an equally famous retort by one New York newspaper, “Aerial Petting Leads to Wetting.” He wasn’t so lucky in another accident. Sperry was killed in a plane crash over the North Seas in 1923 while flying in dense fog from England to Holland in a plane he designed himself. Sperry is a member of the Naval Aviation Hall of Honor and the National Aviation Hall of Fame.

(As published in the May 2014 edition of Maritime Reporter & Engineering News - http://magazines.marinelink.com/Magazines/MaritimeReporter)