Offshore Norway: Vessel Operators Team to Improve

A year ago Det Norske Veritas invited all offshore shipowners operating in the North Sea Basin to participate in a joint corporate project focusing on energy efficiency. Seven companies deceided to be part of the project. "This project focuses on operational findings regarding energy efficiency," Knut Ljungberg, Project Manager of this project said. Mr Ljungberg is the Principal Consultant, Environment and Energy Efficiency at Det Norske Veritas in Høvik, Norway. The project is called Energy Efficient Offshore Partners. Phase I which was initiated last fall is about to be concluded. Phase II will start in fall 2012. The companies participating were Siem Offshore, Farstad Shipping, Havila Shipping, BOA Group, Eidesvik, Gulf Offshore Norge and Solstad, decided to participate in the project.

The objective is to identify, assess and describe ways to operate more efficiently. "These companies all operate technically advanced vessels and have complex operations, and, this is important, none of them pay for fuel. It is the charterer who pays for the fuel." Mr Ljungberg pointed out this is a key issue. "Whatever efforts they make regarding energy efficiency someone else will get the benefits from it." When asked whether the vessels would receive a better daily rate for this, Børge Nakken, Vice President, Technology & Development, Farstad Shipping, said: "It is coming. In the past the fuel consumption of an offshore vessel was not under evaluation when oil companies should hire a vessel but it has become more important over the years. Now fuel consumption is a strong evaluation criteria, and sometimes you will get a penalty if you have promised something you cannot stand for when the vessel is in operation." As there are so many ways you can define fuel consumption, a part of the project is to find some parameters for defining fuel consumption. "We have also seen, at Havila, from operations out in the field that the captains or chief offiers have been asked from the charterer about reporting the fuel consumption after having operated within the 500 meter zone around the rig on DP, when leaving," Einar Åmås, Operations Coordinator at Havila Shipping, added. "This is apparently getting more important. We can show the owners that we are actually focusing on it. That is an advantage."

Goals of the project were: to receive an overview of the leading practices in the industry, to learn about key strengths and weaknesses and areas of improvement, to develop best practise guidelines the companies can use of how to operate energy efficiently, to highlight the responsibilities these companies actually take, and to get a fair an common structure for reporting fuel consumption. "We think this project will also work as a platform for other issues in the future," Ljungberg said.

The process

DNV assessed the operations of the companies and interviewed in all some 80 key people in the organisations. Questioneers were sent to the vessels and close to 400 responses were received, to get an idea of the current working practises. Workshops were arranged among the participants to discuss the various issues from the observations made through the questioneers in order to find solutions to improve. All recommendations were developed into Best Practise Guidelines. A meeting was arranged with the customersof the participants, i.e. the oil rig operators, on how the contracts and agreements could be inproved on, together.

Dividing the 179 vessels into their segments of Platform Supply Vessels (76), Anchor Handlers (68), and Offshore Construction Vessels (35), some initial observations were made. This fleet is young, fairly advanced and some of the vessels were difficult to operate. The environmental performance is high on the agenda for all the companies. The technical competence of the people operating these vessels is high. "There are some areas all of them can improve. That is in performance management," Ljungberg said. "It is absolutely necessary that we get the charteres involved in improving the situation." The Best Practise Guidelines with all the recommendations and the rationality behind them are included in the DP Guidlines, now handed out to the companies.

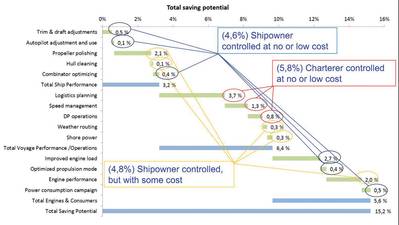

Ljungberg presented a graph with the overall improvement potential for the group of companies, combining the different vessel segments. It shows that adding a number of different improvements sums up to a 15.2% reduced fuel consumption potential for this fleet of vessels. Notable is the small potential for hull cleaning, resulting from the small hull fouling when operating in the North Sea. Engine performance improvements derives both from operating the engines in an optimal way and also by servicing the engines for top performance. Optimizing trim and draft, adjusting the autopilot, improving the engine load etc. results in total savings of about 5%, and are issues controlled by the shipowners. These can also be done at relatively low cost. Propeller polishing, hull cleaning, weather routing, shore power, engine performance are also controlled by the shipowners, but to some costs and the benefits are received by the charterer. Improved logistics planning, scheduling, fleet management, DP operations are are controlled by the charterer to a large extent, whith very small associated costs. The ships are told to be by the rig at a specific time. Also the speed of the vessel is often ontrolled by the charterer. "It does not take much to organise your DP systems more efficiently," Ljungberg said. Mr. Nakken from Farstad Shipping added: "I think it is also a challenge for the oil companies to educate their rig owners and and the offshore installations because very often it is difficult for the oil companies to direct the rig. You have an agreement with the rig, you shall be there at a certain hour, even if there is an agreement in writing the rig is not prepared for the vessel so you have to stay and wait for four, five hours, because they have not done their homework prior to the vessel's arrival. I know there are oil companies which are struggling with the other end of the value chain." Ljungberg summarized: This is the Gordian knot. "When you charter in a vessel you have the same problem. You do not completely control the vessel but you pay for the fuel. A lot of technical ship management companies are frustrated, because they would like to do improvements to their vessels but it is difficult to get the benefits, so they call back."

Phase II

"Now we are looking into Phase II - how to resolve these issues," Ljungberg said. "We think, looking back at the numbers, that it is fairly straightforward to do something with the shipowner controlled 'no or low cost initiatives', which are about 5%. The charterer controlled initiatives, about 6%, may be realized by joint initiatives. Among things are improved communication and clear roles and procedures. The measures controlled by the shipowner which have some costs, about 5%, may be realized through the introduction of agreements with incentives, such as green contracts, or environmental contracts. Some 17 charterers have been invited to take part in Phase II.

"Some charterers have a general focus on it and have many fuel related questions in the tendering phase, but most of them are actually not," Mr Åmås said. Mr Nakken added: "I also have to say it is a very long distance from the Board Room of the oil company to the Contract Manager, so the CEO can make nice speeches about the environment and the priorities and values, but when you come to the Contract Manager, 25 steps down the chain, he is worried about his budget. That is the important thing for him. That is something we clarly see, one hand is not seeing what the other is doing." He added that there is an increasing focus on emissions and fuel efficiency among charterers. "Sometimes it seems a little strange when they are concerned about the day rates talking about a few thousand Norwegian Crowns but do not care about the fuel consumption," Åmås commented.

The shipowners point out that the oil companies also pay a market price for their fuel, so they should have the same incentive as the others. "The charterer should keep the vessel on hire also during the day the owner cleans the hull, and is paying for the cost of divers etc., as it would be a win-win situation for both," Mr Nakken proposed. "If a vessel like this earns say USD30,000/day more or less, they should pay even if we are alongside that day. It should be a fairly clear calculation to see that spending one day cleaning the hull and the propeller every six months would pay in saved fuel consumption in a few weeks. You can also make a too tight schedule, meaning the vessel has to go with full speed, which is not necessarily optimal."

Incentives

"When you talk about incentives you come to the question of measuring," said Ljungberg. "You have different conditions from voyage to voyage. What you can do is to measure and track the consumption of a vessel for different operating conditions. You can also measure what people are doing. I think this is what we are going to focus on mostly. You can measure how often the propellers are polished, how well maintained are the engines, is the vessel trimmed optimally, and soforth." He shows an example of a balance score card, for a fleet of PSVs. "These are fairly simple to make up and maintain, and can be used for evaluation." In the Energy Efficient Offshore Partners' study cards are made for each vessel. The data is coordinated by DNV but is available only for the owner of the vessel. Phase II of the project, now in the phase of gathering participants, will run well into year 2013.

(As published in the September 2012 edition of Maritime Reporter - www.marinelink.com)