Weather Channel Forecasters are predicting a “near-average” hurricane season for 2016, but warn that an average season does not mean businesses and residents shouldn’t prepare for the worst. While it is unclear whether the season, which began June 1, will bring about a few mild storms or a catastrophic Category 5 hurricane, one thing is for sure: safety and preparation are on the radars of the owners and operators of brownwater vessels.

Although forecasters consider this year’s predicted 12 named storms “average”, one only has to look back to 1992 when one of six predicted named storms that year was Hurricane Andrew, which left 65 dead and pummeled Florida to the tune of $25 billion, according to the National Hurricane Center.

In this article, we examine how the maritime industry, particularly the brownwater sector, is making strides in the areas of preparedness and safety – whether their risk exposure involves a threatening hurricane on the horizon, an older vessel with specific risk characteristics, or a new crew member, who may be a little wet behind the ears.

In recent years, improvements have been made in all areas of safety as vessel owners and operators have embraced the fact that high safety standards protect not only the lives of their crew and the seaworthiness of their vessels, but also – their bottom lines. Tougher regulatory standards as laid out in the U.S. Coast Guard’s recently released final Subchapter M regulation, advancements in crew training, and formalized safety procedures are changing what safety and preparedness mean for the brownwater industry.

A New Regulatory Standard for Safety

Making headlines in brownwater safety is the U.S. Coast Guard’s Subchapter M final rule, just released but many years in the making. The regulation, imposes safety inspection requirements on tugboats and towboats.

The regulation stems from a 2004 safety directive by the U.S. Congress to the Secretary of Homeland Security due to accident and injury rates. From 2002-2013, towing vessel accidents were responsible for 18 deaths and 37 reported injuries a year on average, according to the Federal Register notice. Those fatalities, while tragic, also cost the industry nearly $165 million; the injuries led to another $25 million in expenses. Additionally, during the same time period, the industry experienced incidents that led to property damage with a total price tag of more than $50 million.

The regulatory call for a “full safety inspection of towing vessels,” was in part the result of two specific unfortunate incidents, which led to 19 deaths. The first incident occurred off South Padre Island, Tex., where a towing vessel hit a bridge causing it to give way and kill five. The following year, another tragic incident occurred when a towing vessel cruising on the Arkansas River hit a highway bridge in Weber, Okla. killing 14.

As a result, the new rule proposed in 2011, and finally refined this June after taking industry comments into consideration, creates a “comprehensive safety system that includes company compliance, vessel compliance, vessel standards, and oversight in a new Code of Federal Regulations subchapter dedicated to towing vessels.”

All U.S. towing vessels over 26 feet or those carrying oil or hazardous cargo are subject to the new safety requirements. In addition to the rules for inspection, the regulation also lays out new standards for “design, construction, equipment and operating of towing vessels.” The Coast Guard will require retrofits, new propulsion systems, electrical, steering, and navigation systems among other things. Older vessels are given exception to some of these requirements through a grandfather provision. In all, the new regulation is expected to impact more than 5,000 tow boats and initially cost the industry more than $15 to $26 million per year, according to the Federal Register notice.

While the cost of this regulation may seem high initially, it will also lead to cost-saving benefits including: reduced risk exposure to accidents for these vessels, as well as less congestion on waterways and fewer delays, both of which often lead to business interruption and lost productivity. As a result, this uniform safety benchmark for these vessels should greatly benefit tug owners and the entities with whom they contract, not to mention those who insure them as there will be far greater transparency related to vessel condition.

Crew Training in Tandem with a Good Safety Plan

Another aspect of safety on which smart brownwater owners and operators are increasingly focusing is crew training.

Training is key in many professions, but it is of particular importance to those who are in charge of the lives of others. Captain Chelsea Sullenberger has said his training was what he relied on as he piloted Flight 1549 to a safe landing on the Hudson River after a disastrous bird strike.

“We turned to our training, we made good decisions, we didn’t give up, we valued every life on that plane—and we had a good outcome,” Sullenberger told the Wall Street Journal.

For the maritime industry, crew training and hiring procedures have been garnering more attention over the past decade. In prior times, it was easier for crew members to get a job on a tug or tow vessel. Now, among other things, these crew members must have strong resumes, relevant on-the-job experience, and undergo drug testing.

One thing marine employers examine closely aside from vessel experience is education. They may look for crewmembers who have completed certain coursework in safety. For example, courses at the Maritime Institute of Technology/Pacific Maritime Institute focus on advanced navigation, radar plotting, firefighting, first aid and CPR, meteorology, bridge management, and dangerous liquids, among others.

The maritime industry has recognized that one unqualified or ill-equipped crew member can be a liability to all onboard the vessel.

Formal Procedures in Place

These days a formal loss and safety plan and hurricane plan, should be standard aboard any tug or towing vessel. The National Transportation Safety Board recently provided a tip sheet for mariners focused on good preparation and proper use of safety equipment. These tips should be part of vessel formal safety procedures:

- Crew is familiar with an easily accessible weather preparedness plan that reviews low pressure systems and other weather

- Crew is familiar with and regularly practices with onboard safety equipment

- Crew knows the evacuation plan and each crewmember’s emergency supply duties

- Crew conducts regular drills

- Crew carries easily accessible emergency position indicating radio beacons (EPIRBs) and/or personal locator beacons

- Crew has been instructed to stay close to each other if abandoning ship for the water

One way vessel owners and operators can be sure they have a strong reliable safety and preparedness plan is to seek the expertise of their insurer’s risk management team. These risk engineers are trained to review crew and vessel safety and offer suggestions on how to mitigate any unnecessary risk exposures.

A Benefit to All

In all, these improvements and focus on safety in the brownwater industry will be critical for a few reasons. With the implementation of Subchapter M on the horizon, and a renewed industry focus on training, safety and preparedness, vessel owners are likely to be on top of their game – making sure their vessels and crew are ready for anything that may come their way.

In the end, not only will these initiatives save lives – those of crew members and possibly innocent bystanders – but they will likely improve a vessel’s seaworthiness, possibly extend the life of the vessel, and keep the vessel operational with less disruption, thus improving the owner’s and/or operator’s profitability and peace of mind for the future.

It’s Hurricane Season. What’s in Your Safety Plan?

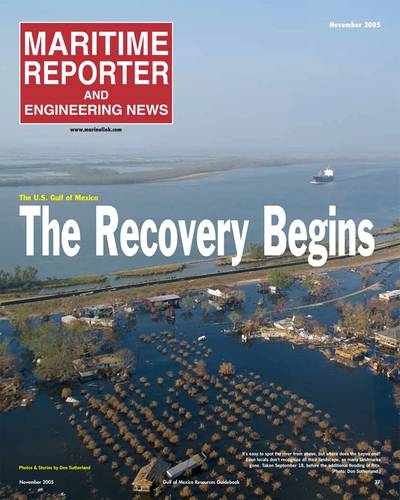

If there was one positive outcome to the catastrophic devastation that Hurricane Katrina caused over a decade ago, it is an increased focus by vessel owners and operators on hurricane safety and preparedness planning.

When developing a hurricane safety plan the following should be taken into account:

- Make arrangements in advance for the docking of a vessel at an alternate location.

- Know your plan of action defined by the U.S. Coast Guard

- Name and train those responsible for preparing the vessel for the storm

- Define how crewmembers will be protected in the event of a storm

- Define how crewmembers will monitor the forecast

- Follow a hurricane avoidance plan

The Author

Damon Vaughan is senior vice president at Tidal Marine, a commercial marine insurance program administered by Venture Insurance Programs. He has specialized in marine business, both primary and reinsurance for 20 years, working in London, Bermuda and New York. Tidal covers a wide variety of commercial marine vessels including supply, utility, and crew boats, to tugs and barges.