Protecting Ports from Sea Level Rise

Coastal flooding disasters have occurred periodically through history often followed by construction of flood defenses to help ensure it does not happen again. One of the most well known was the 1953 North Sea Flood in the Netherlands when a storm surge occurred on top of astronomical high tides causing thousands of deaths, property and economic damages. The Dutch and UK reacted and increased construction of sea defenses including storm surge barriers, such as the Delta Works and River Thames barriers. In the US the New Bedford/Fairhaven port was severely flooded by hurricanes in 1938 and 1954 causing $8.3 million in damages, which lead to the construction of the New Bedford Hurricane Barrier in 1962 by the Army Corps of Engineers at a cost of $18.6 million. The Army Corps project summary notes that this barrier has since prevented $24.1 million in flood damages (to 2011), and properties within the protected area are no longer required to purchase FEMA flood insurance. The Port of New Bedford does emphasize they are one of the safest ports of the eastern seaboard with the storm and flood protection provided by the hurricane barrier.

More recently, Hurricane Ike caused storm surge damage to Galveston in 2008 and a feasibility study is underway by the Army Corps of Engineers, with an Ike Dike concept design being advanced by Texas A&M University. Similar concepts for a hurricane surge protection barrier are being progressed for the New York-New Jersey Harbor in the wake of Hurricane Sandy, with the most feasible barrier connecting Long Island to Sandy Hook. Common to the existing and proposed storm surge barriers are three main elements: dike; tidal flow gates and navigation gates. The dike and tidal flow gates are existing traditional engineering technology, aided in the modern age with computer modelling of the harbor to size and locate the tidal flow gates to maintain water quality and to minimize current velocity at the navigation gates. The navigation gates hold the largest engineering challenge, balancing demands for the widest possible gate opening, against cost and engineering to develop an economically viable barrier design.

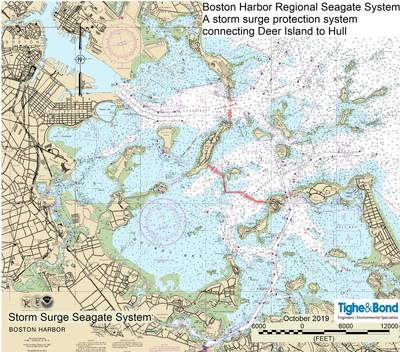

The largest storm surge navigation gate is Maeslant Barrier in the Netherlands at 1,200 ft wide as a single sector gate comprised of two rotating floating sector leaves. St. Petersburg has a similar floating sector gate 650 ft wide. New Bedford also has a sector gate 150 ft wide, but the gate leaves are on wheels. The Bubba Dove floodgate in Louisiana uses a floating barge gate 250 ft wide and is reported to have been one one-third the cost of a sector gate. A similar floating barge gate has been proposed for the Galveston navigation gate, 787 ft wide. Some of the existing navigation gates in exposed waters are around 40% wider that the ship beam, while lock type gates in protected waters with alignment fendering may only be 6% wider that the ship beam. A recent concept for a storm surge barrier across the outer harbor islands in Boston uses redundant multiple navigation gates, with some separation, and PIANC guidelines suggest 380 ft wide navigation openings for 140 ft beam vessels (170% wider than the ship beam).

With the heightened concerns about sea level rise, perhaps more frequent severe storm surges and the severe economic damages caused by coastal flooding, there does appear to be increasing interest in and demand for storm surge barriers. The possibility of a large, once in a lifetime, infrastructure funding bill by the federal government has also primed the pumps to have these storm surge barriers advanced to at least feasibility level. This can be a significant benefit for ports, with the opportunity to market enhanced cargo safety that may not be offered by competing ports. However, these structures will need to be well designed, with adequate clearances and approach fendering for safe vessel passage, with allowances for future ship size increases (width and depth), and unknown future sea level rise.

About the Author

Duncan Mellor, PE is the Principal Coastal Engineer for Tighe & Bond, based in Portsmouth, NH, with over 30 years of experience assessing and designing waterfront structures.