Avoiding the Edges of the Sea

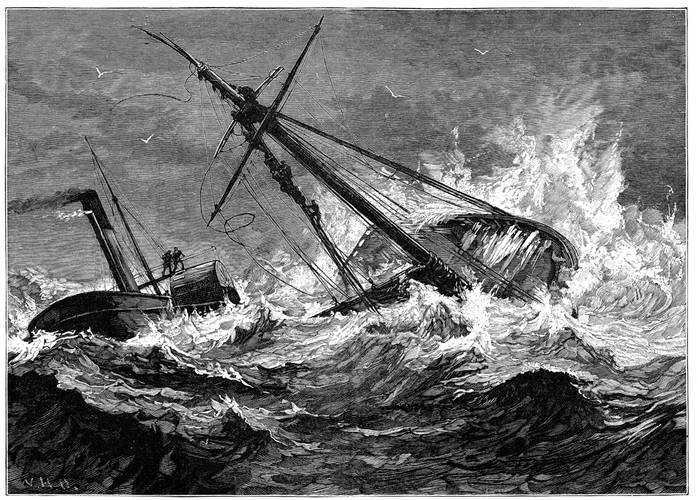

Mariners do best when they avoid the edges of the sea – the shoals, rocks, and other hard spots. Coming into contact with the edges of the sea at other than a slow walking speed can ruin an otherwise pleasant voyage.

Unfortunately, though, vessels have been making hard contact with the edges since Noah’s Ark grounded on Mount Ararat, rendering the Ark unseaworthy.

For a while, it was thought that the leadline would reduce groundings, but one can’t be swinging the leadline constantly.

Lighthouses were another early means of identifying hard spots by means other than direct contact. Lighthouses, though, couldn’t be erected everywhere and sometimes the light was extinguished or otherwise not visible. On other occasions, the light was misinterpreted.

The first electronic aid to navigation – the radio direction finder or RDF – was seen as a means of providing vessels and their navigators with improved positioning information, thus lowering the risk of coming into contact with the edges of the sea. Faith in the RDF was proven to be misplaced on 8 September 1923 when seven US Navy destroyers, travelling at full speed, grounded in the fog on charted rocks at Honda Point near the north end of the Santa Barbara Channel. Due to poor visibility, the ships, transiting as a squadron from San Francisco to San Diego, were utilizing dead reckoning. A radio signal from a new RDF station was received but misinterpreted. Twenty-three sailors died in the grounding. Two other destroyers grounded briefly, but refloated themselves. Five destroyers from the rear of the formation were able to avoid grounding. The squadron commander and the squadron navigators, as well as the commanding officers of the seven destroyers that were lost, were all court-martialed.

Radar has proven to be good at assisting mariners in avoiding groundings, but only if it is operating properly and the deck officer on duty is knowledgeable in its use. Sometimes the radar is ignored. Other times it is set on the wrong scale. Radar, though, is only minimally helpful for avoiding low-lying land. It is completely unable to identify shoal water. In those cases, the mariner must rely on other means to identify the danger. Over-reliance on or misinterpretation of radar may lead one to a false sense of security.

On 16 March 2011, the bulk carrier Oliva, carrying 60,000 tonnes of soya beans from Brazil to China, grounded off Nightingale Island in the Tristan da Cunha archipelago in the South Atlantic. At the time, the vessel was travelling at full sea speed (about 12 knots). Transit was planned using the great circle route from Santos, Brazil around the Cape of Good Hope. Unfortunately, the navigating officer used an inappropriate scale in plotting the various legs of the passage. Rather than laying a course to pass ten nautical miles to the southeast of Nightingale Island, the plotted course took the vessel directly to the island. At sea, the vessel was steered primarily by means of autopilot fitted with GPS input. The officer of the watch at the time of the incident saw something ahead on the radar, but thought that it was merely the return from the low-lying storm clouds that he had observed. He did not realize that the clouds were directly over and obscured the large (and hard) island. The grounding ripped open the bottom of the vessel, but the crew was able to evacuate to a passing fishing vessel. The soya beans and the 1,700 tonnes of fuel oil from the Oliva spilled into the sea. Numerous seabirds and other sea life died as a result. The wreck was left to slowly succumb to the sea.

Not all the edges of the sea are natural, some are manmade.

The container ship Cosco Busan allided with a tower of the San Francisco-Oakland Bay Bridge on 7 November 2007. The ship was equipped with modern electronic chart display and information system (ECDIS) navigation equipment, which overlaid the radar display with navigation chart information. The pilot was unfamiliar with the operation of the installed equipment, but proceeded regardless to take the vessel to sea in dense fog. Approaching the bridge, he became confused between the markings for the various towers of the bridge and open channel between the various towers. He tried to ask the crew for guidance, but was prevented from doing so by language difficulties. As a result, the ship made heavy contact with the Delta Tower, tearing open the hull in way of the bunker tanks. A large volume of heavy fuel oil spilled into San Francisco Bay, causing significant property and environmental damage.

On 18 September 2013, the chemical tanker Ovit grounded on the Verne Bank in the Dover Strait. Fortuitously, there were no injuries, no pollution, and only superficial damage to the vessel. The tanker was utilizing its electronic chart display and information system (ECDIS) as its only means of navigation. The passage from Rotterdam to India was planned by an inexperienced and unsupervised junior officer. Utilizing the wrong scale, the junior officer laid out a course passing directly over the Verne Bank, which was properly charted and showed a water depth less than the draft of the tanker. The tanker’s position was monitored solely against its intended track as programmed into the ECDIS. The officer of the watch exercised such poor situational awareness that the tanker was aground for nineteen minutes before he so realized.

As noted by the UK Marine Accident Investigation Branch (MAIB) in its report on the Ovit grounding, there are over thirty manufacturers of ECDIS equipment, each with their own designs of user interface and little evidence that a common approach is developing. Generic ECDIS training is mandated, but it is left to flag states and owners to decide whether or not type-specific training is necessary and, if so, how it should be delivered.

While the edges of the sea are most frequently found on rocks, shoals, and docks, they may occasionally be encountered overhead. These edges may consist of high-tension wires or gantry cranes, but more frequently they consist of bridges over troubled waters. On 26 September 2013, the Military Sealift Command (MSC) ro-ro ship USNS 1st LT Harry L. Martin was being towed up the St. Johns River in Jacksonville from one shipyard to another. As it passed under the John Mathews Bridge, its elevated stern ramp made hard contact with the bottom of the bridge span, causing significant damage to both the ship and the bridge. Investigation revealed that the air draft of the ship was five feet greater than shown in the vessel’s records. Investigation also revealed that the air gap of the bridge was six feet lower than shown in the records of the bridge owner and the federal government. The lesson here is to not blindly accept everything in writing. It pays to occasionally double-check. The hard edges can be anywhere and everywhere.

Rudyard Kipling had the increased automation of ships in mind when he wrote the Forward to the selection of his prose and verse entitled “A Kipling Pageant” in 1935. That Forward, written as a Letter or Bill of Instruction from the Owner of the Motor Vessel Nakhoda to the Master, included the following:

This new ship here, is fitted according to the reported increase of knowledge among mankind. Namely, she is cumbered, end to end, with bells and trumpets and clocks and wires which, it has been told me, can call Voices out of the air or the waters to con the ship while her crew sleep. But sleep thou lightly, O Nakhoda! It has not yet been told me that the Sea has ceased to be the Sea.

As predicted by Rudyard Kipling in 1935, we have reached the point where technology has instilled a false sense of complacency in many mariners. Technology only performs its designed tasks if properly programmed and utilized. It takes special training to operate many of the systems currently found on merchant vessels. Having an Operator’s Manual placed on the bridge is wholly insufficient. Even with the best of technical training, mariners wishing to avoid the edges of the sea should reply most heavily on experience and seamanship.

(As published in the November 2014 edition of Maritime Reporter & Engineering News - http://magazines.marinelink.com/Magazines/MaritimeReporter)