The New York Bight – a Hydra of Difficult Issues

The greening of America’s energy signature will not come without the usual discussions, regulatory oversight – and opposition from a raft of special interests.

Amidst an atmosphere of possible resurgence in the domestic offshore oil energy, maritime stakeholders are also reminded that there is more than one kind of energy available for development off the four collective coasts of the United States. That process is underway in the Great Lakes; it has already happened off of New England. To that end, and last April, the Department of the Interior’s Bureau of Ocean Energy Management (BOEM) published a ‘Call for Information and Nominations.’

This ‘Call’ started a formal process for BOEM to gather information about developers’ interest in commercial wind energy leases in the Atlantic outer continental shelf. More specifically, this meant within sections of the New York Bight, the portion of the Atlantic extending northeasterly from Cape May Inlet in New Jersey to Montauk Point on the eastern tip of Long Island. The comment period was first set to close at the end of May, but it was extended to the end of July.

BOEM will use the comments to first gauge the interest among energy project developers, and secondly, to assess the broader concerns associated with possible wind energy projects within the Bight. There already is interest in this set of Call Areas. In December 2016, for example, BOEM received an unsolicited lease request from PNE Wind USA, Inc. (PNE) for 40,920 acres offshore New York. PNE seeks a lease to develop a 300–400 MW project, primarily within the Call Area Fairways South. Beyond this, BOEM’s map lists Statoil, US Wind and Ocean Wind as also having interests in various lease areas.

Curiously, offshore wind – that long awaited renewable source of energy – has as many detractors as its dirtier fossil fuel cousins.

- Stepping into the Bight

Potential wind energy areas (WEAs) comprise just a portion of the total Bight. Nevertheless, it’s a big portion, approximately 2,047 square nautical miles. The Call Areas were developed in conjunction with New York State’s interests in getting started on offshore wind energy projects. BOEM writes that “based on a power density ratio of 0.01 megawatts (MW) per acre, New York’s goal of procuring 2.4 gigawatts (GW) of offshore wind energy by 2030 could likely be accommodated by developing just 14% of the call areas presented. Development of approximately 18% of the Call Areas would be required to meet New York State’s recommendation that BOEM designate four 800 MW lease areas (3.2 GW of capacity).”

Today, for mariners, the New York Bight is largely wide-open seascape. Navigationally, though, it does have limits. The entire length of Long Island, for example, on the Atlantic side, is a “regulated navigation area.” A “precautionary area,” SE of Cape Cod, starts [two] 250 mile east-west traffic lanes and a formal separation area which lead directly into the Call Areas. Within the Bight there are currently six traffic lanes and three separation zones. They all lead to one place: The Port of New York and New Jersey, the largest Port on the Atlantic coast, third busiest in the Country.

Depending on how potential wind projects develop, some mariners fear that the New York Bight could turn into a Manhattan street grid.

As one would expect, BOEM sought comments from a wide range of ocean-related interests. Just some of these stakeholders can be seen in figure 1, shown below:

Fisheries | Navigation | DoD and USCG Training Areas |

Avian Species | Recreational Port-to-Port Transit | Bathymetric Conditions |

Marine Protected Species | Port-to-Fishing Location Transit | Cables |

Visual Impacts | Commercial Vessel Port-to-Port | Other Existing Infrastructure |

At the close of the comment period, BOEM had received 130 comments. Most of the comments, indeed, express support for off-shore wind energy but that support is almost always followed by a big “BUT,” contingencies and caveats qualify almost every comment. With BOEM, the NY Bight Call presents as an energy project. In fact, it’s a tangle of projects. For the maritime industry, the NY Bight Area Call portends a set of issues that mariners will be confronting again and again for years to come. It’s worth a closer look at some of the issues and what’s at stake.

- What’s at Stake

BOEM coordinates with the U.S. Coast Guard (USCG). Readers may recall that in 2015 the USCG completed its Atlantic Coast Port Access Route Study, a set of Marine Planning Guidelines (MPG) that recommended a 2 nautical mile (nmi) parallel buffer between the outer or seaward boundary of a traffic lane and offshore structures, and a 5 nmi buffer for a Traffic Separation Scheme entry or exit. Based on these MPGs, BOEM writes that some portions of the Call Areas may be placed off limits depending on information received about safety and historic routes of vessel traffic.

The Coast Guard’s Call Area comments are written by George Detweiler, Office of Navigation Systems, but signed by Michael D. Emerson, Director, Marine Transportation Systems (MTS). Detweiler writes that the Coast Guard has “several equities” tied to offshore renewable energy. Top concerns include:

- Implementing and undertaking basic CG duties: protecting infrastructure, emergency management, navigation safety, and maritime security. “The Coast Guard will adapt to the changing environment in order to accommodate maritime commerce,” Detweiler writes, “but will generally oppose priorities that place undue strain on the MTS, reduce navigation safety or impede execution of our statutory missions.”

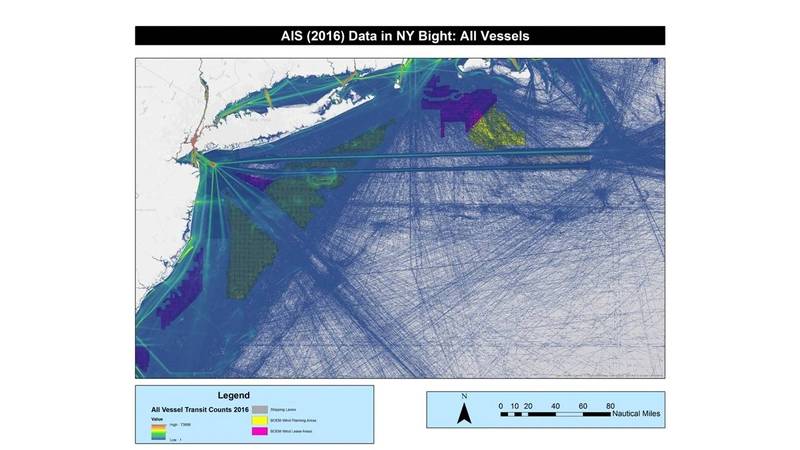

- Operationally, the Bight presents complicated maritime territory: Detweiler’s comments include six schematic maps – pictures worth at least a thousand words – to demonstrate how heavy this traffic is and the constancy of vessel routes. (See AIS 2016 Data in NY Bight.)

- The Ports and Waterway Safety Act: authorizes the CG to designate shipping fairways that keep areas free of fixed structures. The Call Area request comes at a time when the Coast Guard is developing a regulatory initiative to convert traditional high-density maritime traffic routes into shipping safety fairways.

Maritime trade groups are closely watching these energy related developments. Brian Vahey is Senior Manager, Atlantic Region for The American Waterways Operators (AWO). A particular concern for Vahey is tug movements from Barnegat, NJ (20 miles north of Atlantic City) to Montauk, on the eastern tip of Long Island. This transit is a common, northeast routing that cuts through almost the middle of the proposed wind energy areas. Vahey notes that BOEM seeks to accommodate traditional tug routes heading to New York Harbor and he suggests a similar carve-out for traffic from mid-New Jersey to Long Island, suggesting a 9-nm-wide lane through the proposed WEAs.

That suggestion might make sense from a maritime safety and efficiency standpoint, but at the same time, it highlights tough policy questions: how much ocean territory can you place off limits and still meet the parameters necessary for affordable, large-scale yet efficient (not to mention clean and renewable) energy production? To what extent should one set of concerns take priority over another?

Edward J. Kelly is Executive Director of the Maritime Association of the Port of NY/NJ. Kelly cites many Call Area issues needing close attention. Kelly asks BOEM to make the safety of marine navigation “the overriding factor when considering offshore development.”

Kelly refers to what he calls “funneling,” compressing vessel traffic into smaller and increasingly limited spaces. These smaller spaces present new challenges and risks, from operational and speed changes to, of course, collisions with other vessels or energy structures, a calamitous prospect for any vessel but one with particularly ruinous overtones for an accident involving oil shipments. Mariners could try to avoid restricted spaces by operating further offshore, again, though, that presents consequences.

Kelly cites another concern likely not too familiar to the general public. He notes that many of the proposed WEAs are located where large vessels must transfer from heavy fuel to low-sulfur fuel “and in the event of even a temporary power loss, will be subject to immense sail-effect and sea-surface drift potential.” To his point, the state of California, an early adopter of the so-called ECA areas that Kelly references, had more than its share of ‘loss of propulsion’ incidents. Arguably, the teething era for that sort of thing is coming to an end.

Separately, the North American Submarine Cable Association adds its own perspective to the discussion, saying, “Renewable energy projects on the New York Bight OCS pose significant risks to submarine cable infrastructure. Submarine cable installation, operation, and maintenance activities require spatial separation from other cables and other marine activities – including offshore wind projects – as recognized by various industry standards and recommendations. Absent sufficient spatial separation and coordination, wind energy projects threaten submarine cables with direct physical disturbance and impaired access to submarine cables both at the surface (for cable ships) and on the seafloor (for cables).”

Meanwhile, Rutgers University, since 1992, has operated the Rutgers Center for Ocean Observing Leadership (RUCOOL) focusing on “understanding the interactions between physics, chemistry, and biology in the world’s ocean and the corresponding impact on human society.” The Center presents analysis on a number of Call Area issues, from projected wind speeds to fisheries.

Rutgers’ expansive comments touch upon many things, including the domino-like line-up of issues characterizing the start-up of a new industry. “The High Frequency (HF) Radar Network operated in the Mid Atlantic, utilized by the US Coast Guard (USCG) for search and rescue and by NOAA for oil spill response, will be impacted by the deployment of offshore structures. These impacts can be mitigated with real-time information on the turbine movement.”

- Over the Horizon, but on the Radar

Next steps for BOEM, according to a spokesperson, include staying in touch with affected states and stakeholders to identify potential offshore wind development sites. BOEM is analyzing the comments and nominations that submitted in response to the Call. This Fall, BOEM will hold public meetings with affected stakeholders to discuss the feedback received and the analysis as it stands at that time.

At a time when offshore wind finally seems ready to flourish on this side of the pond – decades after it has been proven at least operationally feasible offshore Europe – it is also clear that the regulatory process that would allow it to happen will be no less onerous than that which has historically dogged the oil industry. It might just prove to be harder.

Tom Ewing is a freelance writer specializing in energy and environmental issues.

This article first appeared in the September print edition of MarineNews magazine.