Passage to the High North – When Spray Matters

Why bother about a bit of spray? In mild climate latitudes rain and spray water is hardly a concern; it will run off and the ship happily carries on. But going to the High North it’s different.

With the economic development of the High North and Arctic areas, partly driven by the reduced ice conditions and partly by opportunities to develop oil and gas and scarce mineral resources, maritime operations in these areas are booming. But safety of the environment, crew and their ships is of prime concern. In the Arctic, global warming doesn’t mean milder conditions.

One of the operational aspects to be considered is icing, formed by precipitation and through seawater spraying onto the ship in cold weather. A major hazard leading to intense icing is a so-called ‘Polar Low,’ which are small, low-pressure systems developing into storms with sharp temperature rises – typically from -20 to -1 ˚C – and this is combined with precipitation. A ship in these conditions will be cold, plus the seawater is cold and spray and precipitation will stick.

Time Domain Simulation

In the SALTO JIP icing is one of the parameters considered in the time domain simulation for operations in Arctic conditions. In the metocean modelling, provided by the Danish Meteorological Institute, precipitation icing is computed, while MARIN has formed a cooperation with Delft University to develop a computational model for seawater spray. This will predict spray volumes and drop sizes and then the thermodynamic and ballistic process in which the spray water will develop an ice cover on the ship.

The generation of spray on a ship in waves is a hydrodynamic No Man’s Land. In the past year a probabilistic model was developed, taking into account the prime elements of spray generation comprising:

• Ship motions

• Above water hull shape

• Bow wave (at speed)

• Wave non-linearity

A thorough examination of high-speed video of large scale waves impacting on a wall, thanks to the Sloshel JIP, found that two mechanisms have to be considered: jet forming due to rapid immersion of a bow section and jet forming due to impacts.

Rapid immersion spray leads to a jet breaking up due to vorticity formed by friction along the hull, according to the well-known Kelvin- Helmholz instability process. The break-up in droplets after an impact event is much quicker and has a close resemblance to the Richtmyer-Meshkov instability process from a shock wave.

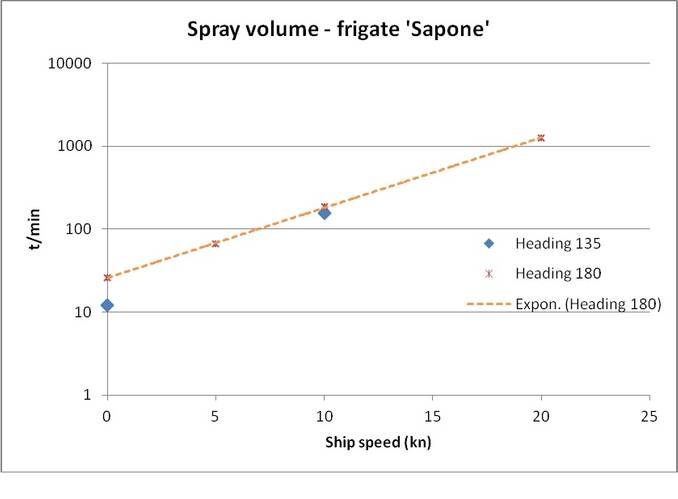

The main step in the modelling process is matching the ship motions in waves to a jet generating process. For this, the hydrodynamic theory of wedge immersion was used. The jet thickness and velocity exceeding the bow height are then computed. Hourly volumes of spray water over the bow can be computed by applying this method to a ship transiting in an irregular sea. There is unfortunately scarce validation material available, although what we have matches satisfactorily. Results were published at the Arctic Technology Conference in Copenhagen in March 2014, thereby inviting the industry and other interested parties to provide further validation material.

The development of a realistic prediction method for bow spray has shown that the effect of bow shape, speed and wave direction are very strong. Previous models could hardly distinguish between ship size and they used only speed and wind parameters to predict spray formation at the bow. MARIN believes that for this reason it is fair to say that a major step forward has been made in the ability to better predict sea spray induced icing.

The Author

Albert Aalbers is Senior Researcher of the R&D Department of MARIN, the Maritime Research Institute Netherlands.

E: [email protected]

(As published in the August 2015 edition of Maritime Reporter & Engineering News - http://magazines.marinelink.com/Magazines/MaritimeReporter)