Marine Infrastructure Challenges Demand Engineering Solutions

Infrastructure renewal and engineering combine to provide an obscure, often under-appreciated, but nevertheless critically important aspect of marine operations. In the Pacific Northwest, for example, the waterway abundant geography provides engineering and specialized moving company Omega Morgan with all sorts of challenges that involve bridges spanning rivers. Whether crossing or moving these spans, West Coast-based Omega Morgan, faces particularly unique engineering challenges. Of particular interest to marine operators, bridge renewals involve potentially severe waterway delays and a marine component that affects all marine commerce. Minimizing waterway delays and downtime there is at the very heart of what Omega Morgan does every day.

Omega Morgan started in the machinery moving and industrial contracting business in 1991, but the firm experienced its most rapid growth during the past six years, partly as a function of aging and critically deficient infrastructure assets. Omega Morgan’s vice president of engineering, Ralph DiCaprio, is no stranger to these challenges, having successfully engineered recent high profile Northwest bridge moves including the Sauvie Island Bridge, the Sellwood Bridge and the Skagit River Bridge. His experience also involves managing the Third Avenue Bridge project in New York City, moving two 900-ton spans on the Hood Canal Bridge, the transport and launch of the Kalama River Bridge, as well as more than a dozen Utah bridge overpass moves.

Jack & Slide: New Nomenclature

The jack and slide method of translating, or moving, bridges provides specific advantages over the destruction and rebuilding of temporary spans until permanent spans can be built. If the river is deep enough, barges or flexifloats systems can also be used to move pre-constructed bridges or bridge components into place. A flexifloat system allows for modular sections to be connected quickly in various shape and size barge configurations that can support various types of heavy equipment.

Omega Morgan has been able to not only save commuters big headaches due to lengthy down time, but has also been able to quickly and efficiently get important infrastructure up and running so that there is minimal impact on neighboring businesses – like yours, on the water. Rather than closing down main thoroughfares, being able to slide over existing spans and detour traffic back onto them while construction of new spans take place means just days of traffic detours and/or disruptions to inland marine commerce, rather than months or even years.

Omega Morgan isn’t the only outfit in this country that has been able to master this method of translating bridges, but remains as that has been able to do so on a massive scale, as was the case with Portland’s Sellwood Bridge. While each of these bridge moves posed their own unique set of challenges, some common themes included the structural limits of the bridge being moved, water depth and specialized insurance considerations.

Sauvie Island Bridge, Portland, OR

The old bridge was classified as functionally obsolete and structurally deficient according to federal and Oregon state standards, scoring 8 out of a possible rating of 100. However, even with temporary repairs, it was not near adequate enough to meet the needs of Sauvie Island’s farmers and industrial businesses. The bridge had a supporting capacity of only 40 tons, and was very near the end of its service life. Construction of the new Sauvie Island Bridge began in early 2006 and was completed in 2008.

The main arch that spans the Multnomah Channel of the Columbia River is 350 feet long and weighs 1,600 tons. The arch is comprised of hundreds of steel components joined by tens of thousands of bolts. It was assembled at Terminal 2 in Portland, loaded onto a barge using a combination of a skidding system and self-propelled dollies. Once the bridge was loaded onto the barge the jacking towers were used to jack the bridge 65 feet into the air. The bridge was secured at height on the barge and moved down river. Once at the final location, the bridge was rotated into place. A special mooring system was used to hold the barge in place while the new bridge was jacked onto its bearings.

The Sellwood Bridge, Portland, OR

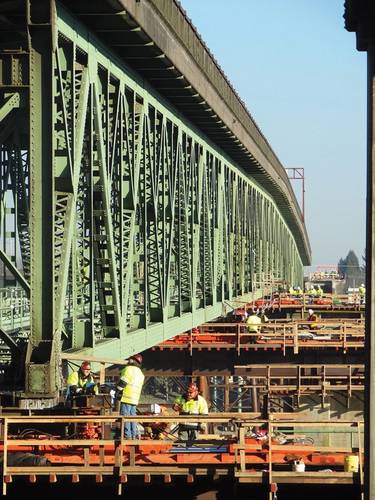

Here, again; engineers were faced with the daunting task of moving a bridge, this time Portland’s 87-year-old Sellwood Bridge. Weighing 6.8 million pounds and measuring more than 1,100 feet long, the Sellwood Bridge was one the longest, most complex bridge structures ever contemplated for relocation.

The plan was for the Sellwood Bridge to be slid over to make room for the construction of a new bridge. If successful, the old Sellwood Bridge would be used by motorists as a detour during construction. The bridge would be closed for just under one week, rather than needing to divert traffic for years until the new bridge is completed in 2016. Omega Morgan was selected by Slayden/Sundt Joint Venture as a subcontractor for the $307.5 million bridge replacement project.

Months of planning and meetings concluded on January 19, 2013 as the bridge was slid horizontally into a temporary location dozens of feet away, inches at a time. As opposed to a traditional vertical pick-and-move, which certainly would have destroyed the existing bridge, engineers developed a horizontal slide method using 14-foot long, ski-shaped steel units that slid on Teflon pads inside track beams.

What made the move even more complex was that the bridge truss needed to be moved twice the distance at the west end than on the east end. Imagine an arc motion much like a windshield wiper, sliding 66 feet on one end, and just 33 feet on the other. Highly specialized lasers and GPS surveying were used by the engineering teams to ensure that the bridge truss was not bent or twisted beyond its tolerance limits so that it was not damaged during translation.

In just 12 hours – a remarkably short time for this type of operation – the bridge was slid over to its new home and opened up just 5 days later for motorists’ use. The alternative to the move, building the new bridge span in two phases, would have cost millions more.

Skagit River Bridge, Mount Vernon, WA

After a truck struck the Skagit River Bridge on May 23, 2013, a portion of the bridge collapsed into the Skagit River near Mount Vernon, Washington. That particular section of I-5, which sees more than 71,000 drivers each day, was out of commission for four weeks until temporary spans were put into place (also by Omega Morgan). Max J. Kuney Construction of Spokane, Washington was awarded the contract to build the permanent bridge, which included the contractual deadline to open the new span by October 1 2013. It was crucial to get the new permanent span in place as quickly as possible as the bridge is a critical economic link on I-5.

Omega Morgan was subcontracted by Max J. Kuney to translate the 915-ton span into place, moving it upriver using flexifloat barges and setting it upon original concrete piers that were retrofitted with new pedestals installed to accommodate the new concrete beam arrangement. The new span was slid into place in just hours, not days, reconnecting the main link between Seattle and Vancouver, BC two full weeks ahead of schedule. The Skagit move was particularly precise, as Omega Morgan had less than two inches of clearance on each side of the 162-foot long bridge.

Special Projects mean Special Considerations

Before any project can take place, specialized insurance underwriting and risk mitigation services must be considered carefully. That’s because the definition of what entails “marine” work and what does not has to be carefully considered. For that reason alone, inland marine insurance underwriting is a specialty unto itself. Many potential exposures exist for marine contractors and subcontractors, like Omega Morgan, when engaging in commercial construction, transportation and heavy lift activities on and around the water. Sometimes liability protection needs to be a combination of marine and non-marine coverage(s) to ensure that each phase of the project is appropriately protected in the rare case of an incident.

As state departments of transportation begin evaluating bridges for replacement or repair, they work closely with contractors and bridge designers to determine the best possible solution for each situation.

Critical Infrastructure, Critically Deficient

The need for specialized engineering and construction methods on and around the waterfront isn’t likely to go away very soon. The most recent federal National Bridge Inventory from the Federal Highway Administration includes 607,380 bridges that are subject to uniform bridge inspection standards. Among those bridges, there were 66,749 classified as “structurally deficient.” A bridge is “structurally deficient” when it is in need of repair or replacement because at least one major component is considered in poor or worse condition, or because it has insufficient load carrying capacity.

As of December 2012, the last time the report was updated, in Oregon, of the 7,633 bridges in existence, 433 are structurally deficient. The story in Washington is very similar: of the 7,839 bridges operating, 366 are structurally deficient. With those kinds of numbers, the need for solid performers in this interesting business sector is clear. Likewise, the future appears to be bright for Omega Morgan.

(As published in the December 2013 edition of Marine News - www.marinelink.com)